Jeff Sessions, the man slated to become the next U.S. attorney general, has a complicated history with the war on drugs. Just ask Stephanie Nodd. Though she was never caught with narcotics, police arrested her in 1990 for a minor role in a crack cocaine ring in Mobile, Alabama. Sessions was the U.S. attorney for the state's Southern District back then, and his office prosecuted Nodd, a 23-year-old single mother and first-time offender, sentencing her to 30 years behind bars. Her four small children were left to grow up without her.

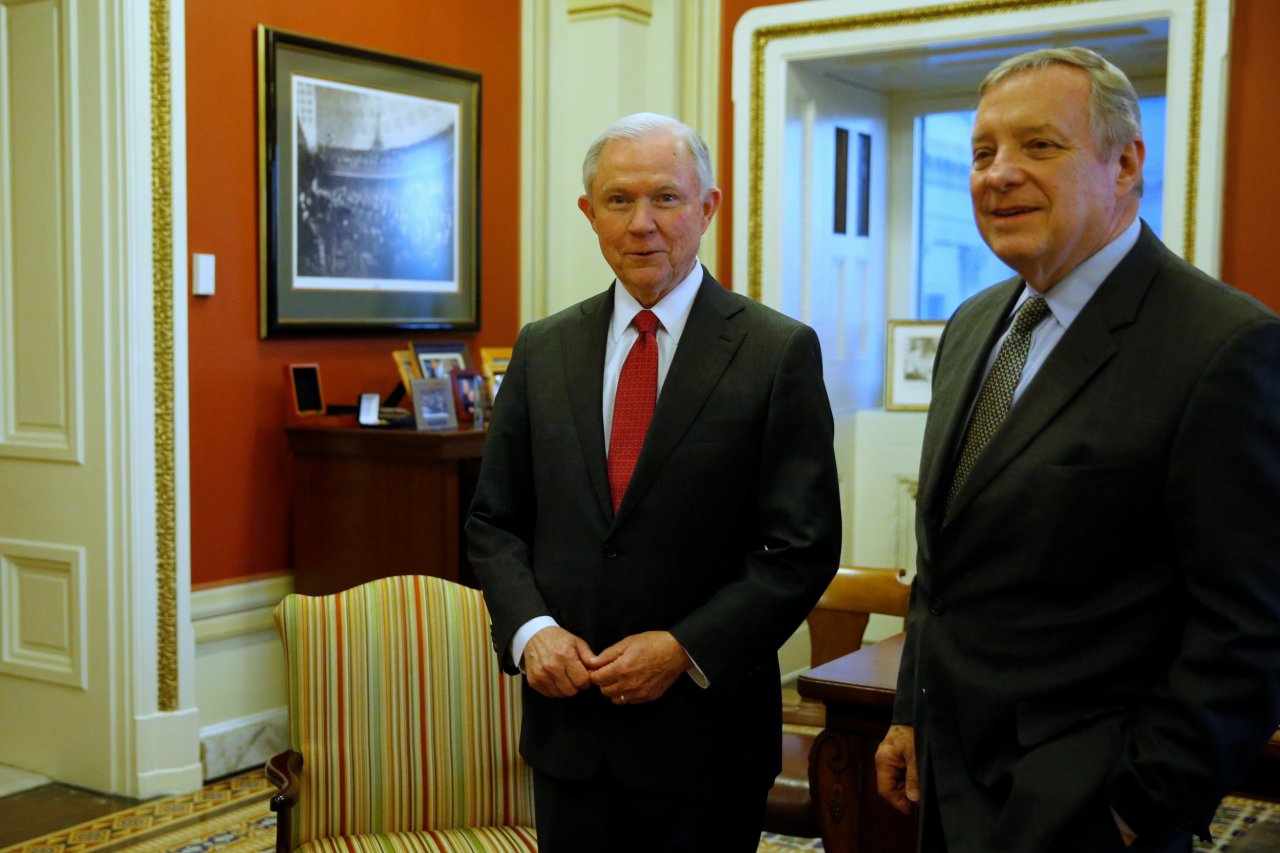

Some 20 years later, Sessions changed the course of Nodd's life once again with a handshake in a locker room 1,000 miles away from Mobile. In March 2010, Sessions, then Alabama's junior senator, along with fellow Republican Orrin Hatch, hashed out an impromptu agreement with Democrat Dick Durbin after encountering one another in the Senate gym before their morning workout, according to The Washington Post.

The deal was to remedy a notorious 1986 drug law with a large sentencing disparity for crack and powder cocaine traffickers. Someone with just 5 grams of crack was required to receive the same sentence as someone possessing 500 grams of powder cocaine—a 100-to-1 ratio. The law also set mandatory minimum sentences for varying levels of crack possession, which is why Nodd got so much time behind bars. The sentencing law was a response to the crack epidemic ravaging inner-city African-American communities. At the time, many thought tough sentencing was the best deterrent to crime. Instead, it further decimated those communities, ensnaring thousands of mostly young, and mostly black, low-level offenders.

The agreement Sessions and Durbin struck reduced that ratio to 18-to-1, not as much as reform advocates wanted but more than what Republicans had proposed. President Barack Obama signed the bill that August. "As a result of it, thousands of years of jail time were spared," Durbin bragged after meeting with Sessions on January 4 to discuss his attorney general nomination.

Still, Nodd languished in jail. The new law addressed only new cases; it did nothing to address those serving decades under the old guidelines. That would come later, when officials decided to apply the law to her case retroactively, cutting six years off her sentence.

Today, Sessions is rightly viewed as a criminal justice hard-liner, and his nomination is being vigorously opposed by Democrats, civil rights groups and a coalition of more than 1,000 law professors, who express concern about his history on racial discrimination and anti-immigration efforts. Defenders, however, and even some reform advocates say his record on crack cocaine is evidence he may be open to compromise on some criminal justice reform issues as attorney general. Democrats aren't buying it, and they plan to make it an issue at his confirmation hearings, which begin January 10.

"He said he doesn't regret what we were able to achieve," Durbin told reporters after his meeting with Sessions. "But when it comes to criminal justice reform that [2010 law] was not the end of the story, that was an important beginning. And I did not sense a continued commitment."

'We Can Wait No Longer'

More than 15 years ago, long before problems with mandatory minimum sentences and prison overcrowding inspired a movement of fiscal conservatives, Christians and progressives to rein in the system, Sessions was one of the few in Congress raising the issue. His initial bill proposed reducing the ratio of crack to powder cocaine for sentencing purposes to 20-to-1, and it decreased the mandatory penalties for those who played only minor roles in drug trafficking.

When Sessions introduced the legislation on the Senate floor in 2001, he acknowledged that the 1986 law had failed to halt the crack epidemic. And while he denied that the disproportionate penalties on crack were explicitly discriminatory, he suggested that "we should listen to fair-minded people who argue that these sentences fall too heavily on African-Americans."

It was another nine years before the U.S. government rallied around that call. By that time, Obama had succeeded George W. Bush in the White House and the Democrats controlled Congress. Sessions was already sounding more skeptical about sentencing reform, and while the senator recognized that crack cocaine penalties were unfair, he adamantly opposed applying the changes to the sentencing law retroactively, denying early release to people like Nodd. In a 2011 letter to the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which was weighing that decision, Sessions and 12 other GOP members of Congress seemed particularly agitated by sentencing reforms the commission had made in 2007—without congressional approval. He pointed out that inmates released early as a result had a similar recidivism rate as other criminals. It is evidence, he argued, that early release "merely gets criminals back into action faster."

Ultimately, the Sentencing Commission ignored the Republican reprimands, citing the law as grounds for the early release of more than 7,700 federal inmates serving extended time for low-level drug offenses. Nodd was one of them. She left prison in 2012, having served 21 years behind bars. "It was like I grew up in prison," she tells Newsweek , while her kids grew up in the outside world. By the time she was released, they were adults.

'We're Just Hurting People'

Going into the final two years of Obama's term, many hoped Congress would finally cut a deal on a package of criminal justice laws that would touch on everything from additional drug sentencing reform, to mental health and substance abuse treatment for inmates, to revamping re-entry programs for released prisoners. Sessions opposed nearly all of those proposals. "We have learned the hard way that a substantial portion of criminals who are released from prison will return to crime and will victimize more people," he warned his Judiciary Committee colleagues last year. Concerns about fairness, it seems, have given way to fear.

Sentencing reform advocates argue that criminal justice can be both fair and tough. "There are states all over the country that are reducing their prison populations, saving money, reducing crime," says Molly Gill, director of federal legislative affairs at Families Against Mandatory Minimums, an advocacy group. "Certainly, incarceration has some crime-reducing impact, but it's not the silver bullet that Jeff Sessions hopes it is." With America's current rate of incarceration—the highest in the world —"we're not even getting marginal benefits," she argues. "Now we're just hurting people and hurting families."

Plenty of Republicans have embraced those arguments. One of the first states to carry out major sentencing reform was Texas, and the leading co-sponsors of criminal justice reform proposals include Senator Mike Lee of Utah (a Tea Party stalwart) and veteran Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa, a traditional law-and-order Republican.

Sessions, however, has not been swayed by the success of reforms in red states like Texas or his home state of Alabama. But much of his resistance appears to be a reaction to what he sees as overreach by the Obama administration—moving too far, too fast. And Sessions has been particularly opposed to executive branch moves to release existing prisoners (like Nodd) early, rather than applying sentencing changes only to future cases.

One of the Democrats' leaders on the issue, Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey, says Sessions has made clear he is "avowedly against the reform efforts that have been going on." And Booker says it is "frightening" that Sessions could soon be at the helm of the Justice Department, where he will have the power to "roll back a lot of the executive decisions that [former Obama administration] Attorney General Holder made that began to roll back mandatory minimums, policies on solitary confinement and more."

But Gill and Holly Harris, executive director of the U.S. Justice Action Network, a coalition of liberal and conservative reform advocates, think conservatives might be able to sway Sessions. Gill says bipartisan interest in passing criminal justice reform remains strong, pointing out that Grassley has made the issue a central talking point. Lee, who's continued to push sentencing reform, had a terse reply when asked if Sessions' support for closing the crack cocaine sentencing disparity gave him hope he could win over his Republican colleague: "Of course."

Nodd, the former inmate, takes less comfort in knowing Sessions supported the 2010 law, even though it ultimately led to her early release from jail. Her time in prison was still far too long, she says, and she doesn't understand how her senator could acknowledge that the law was unjust but not support applying it to more people like her, who have suffered because of it. "I learned from my mistake," she says, but it didn't "take no 21 years."