Clara Rollins was an 18-year-old photography intern at a newspaper in the southeastern United States when a section editor asked her if she'd ever had sex.

The editor sent Rollins (not her real name) several flirtatious texts during her two years at the paper, asking her if she would come to his house and whether she "would do anything for him." A teacher at her high school sensed something was happening and told her to be careful, a warning Rollins says she didn't heed.

The editor implied "I wouldn't get a recommendation from him for any other internships, or further work, if I didn't," says Rollins, now a 23-year-old general assignment reporter. "I didn't know what else to do. I was afraid saying no would mean I wouldn't collect any more clips."

After declining a number of times, she eventually went to his house and asked to watch a movie: "I told him I didn't really want to fool around—that I had changed my mind," she says. Instead, he told Rollins that watching a movie wasn't why she was there. He forcibly performed oral sex on her before she grabbed her clothes and ran out. She was able to avoid seeing him again, but he continued to contact her for two months until she went to college. He's still working at the newspaper.

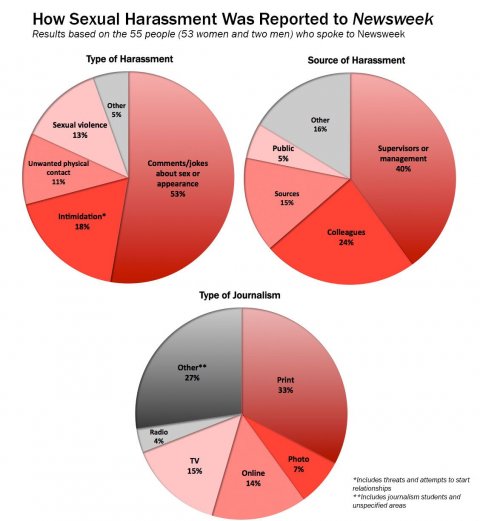

Rollins is one of 53 women and two men who contacted Newsweek about their experiences of sexual harassment and sexual assault related to their jobs in journalism. In mid-July, I emailed friends and colleagues a Google Form seeking stories, posted it on Twitter and Facebook, and was soon inundated with recollections of inappropriate jokes, comments on race and appearance, and unwanted touching and worse by sources, colleagues, bosses and the public. Newsweek has granted anonymity to those who requested it; many women still work at the companies where the harassment happened.

While this is not a scientific survey and it's virtually impossible to know how many journalists have dealt with sexual harassment in their careers, it's an opportunity to hear the stories of women who have faced irritating, intimidating and, at times, life-threatening behavior while trying to do their job as journalists. (Newsweek has not been able to contact those accused of harassment to confirm the reports.)

As a woman and a reporter, I'm not immune to the problem of sexual harassment. I was a 22-year-old intern at an international news organization in Washington, D.C., when an older, married male journalist invited me to go stargazing with him in rural Virginia. When I declined, he sent me an email: "I hope I can count on you as a very mature person and not hear some crazy rumors in the office." That same year, an older male sports photographer detailed the injury of a well-known football player by reaching under the table and tracing lines on my knee and thigh.

Like many women who spoke with Newsweek, Rollins says she continues to blame herself for what happened. "It wasn't until I went to counseling and told my therapist what happened did I realize it was rape. The question of consent never crossed my mind at 18," she says. Five years after the attack, she says, she is unable to cover stories that involve sexual violence due to her post-traumatic stress disorder.

"It was humiliating, not because my boss wasn't accepting—just because I had to admit I couldn't and why," she says. "No one wants to tell that story to their boss."

'Ivanka Is a Strong, Powerful Woman'

Sexual harassment in the media industry has been making headlines again after allegations against former Fox News Chairman Roger Ailes by numerous female staff members, including anchors Megyn Kelly and Gretchen Carlson. Ailes was ousted in July over the claims. Late last month, Laurie Luhn, a former director of booking at Fox News, told New York magazine that she had been harassed by Ailes for more than two decades.

In early August, Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump said his daughter Ivanka would have decided to "find another career or find another company" if she faced sexual harassment at work. Her brother Eric later defended his father's much-criticized comment, saying, "Ivanka is a strong, powerful woman; she wouldn't allow herself to be" subjected to sexual harassment.

Sexual harassment is defined by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission as "unwelcome sexual advances, request for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature." Of course there are distinctions: Casual sexism is very different from rape. Sexual assault is defined as nonconsensual physical contact and can include rape, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network. But sexual comments, jokes and insinuations are also not acceptable and can make a workplace unbearable.

Betsy West, a filmmaker and journalism professor at New York's Columbia University, said that in her experience, sexual harassment of the kind involving sexist or sexually suggestive comments is much more pervasive than assault, but "that atmosphere can lead to a situation where someone who is more aggressive or predatory can take advantage of someone."

Squeaky Wheel

A 2013 study from the International Women's Media Foundation found that nearly two-thirds of women journalists have experienced some form of harassment or abuse in relation to their work. The IWMF survey includes behavior ranging from verbal sexual harassment to more severe behaviors such as intimidation and sexual and physical violence.

The majority of the 822 women polled by the organization didn't report what happened. The ever-changing nature of the media industry, including lack of job security, "absolutely" leads to fewer women telling their managers or other authorities about sexual harassment due to the fear of retaliation, says Elisa Lees Muñoz, executive director of the IWMF.

A recent British study found that more than half of the women in a variety of careers who were surveyed said they'd experienced sexual harassment at work, rising to 63 percent of girls and women between the ages of 16 and 24.

"That perception has always been there—there's always been the fear of backlash," says Muñoz. "[Women] are afraid to say something, afraid of being the squeaky wheel, afraid they wouldn't get assignments, that they wouldn't be sent back to where this happened."

Thinking back to her time working in a Washington, D.C., news bureau nine years ago, Elizabeth (not her real name) remembers how she didn't want to get her male colleague fired. She was a 23-year-old reporter; he was an assistant. They became friends, but she was in a long-term relationship and said no after he asked her out. "I remember him being taken aback when I told him, like he thought I had led him on or something like that. He was definitely offended," she says. "I remember feeling bad."

Soon he began texting her all the time and shifting his schedule to match hers, showing up when she did in the morning. He tried to talk to her about his anxiety issues and told her how unfair it was that he didn't get to write. Returning to the office one day after covering a meeting, Elizabeth found herself alone with him, a position she had managed to avoid for five months.

"He immediately came to my part of the office. My desk was sort of in a corner, and he walked all the way up to me. He was getting angry: 'Why are you such a bitch to me?' 'You really strung me along.' 'You know I have anxiety issues, and you decided to fuck with me anyway,'" Elizabeth recalls.

"At this point, he's literally backed me into a corner. I said a couple of times, 'You need to step back from me.' He was yelling at me but [also telling me], 'We would be perfect together, we should really be a couple.' It got really creepy."

Deeply shaken, she started to spend more time away from the bureau and believes her work suffered for it. Later that year, she was sent to a Middle Eastern city and was struck by the familiar experience of having her movements carefully controlled.

"When you're [in the Middle East], you have to plan every step of your journey very cautiously and very deliberately. You can't just go from point A to point B. I remember thinking, Oh man, I know how to do this," Elizabeth says. "Obviously the level and types of danger were different, but the idea of not just blithely going from point A to point B, elaborately planning out how long you'll stay, was very familiar to me."

Elizabeth did not report what happened to her and says she sees the man who screamed at her retweeted into her Twitter timeline on a weekly basis. "It feels so dangerous to burn bridges in journalism, specifically because everyone ends up working together again and because jobs are alone so tenuous," she says. "The industry is constantly shifting out from under our feet."

The Intern

The majority of women who spoke with Newsweek said their sexual harassment happened early on in their journalism careers, when journalists are hungry for their first job and less likely to report an incident for fear of what might happen. Janille Miller, 39, was in her mid-20s when she interviewed for a broadcast journalism job. After an interview with the news director, Miller went with him to meet the head of news. She says she was asked to stand up and turn around.

"There I was, standing up in front of news director and head of news, both men. I felt humiliated and disgusted as the head of news looked me up and down as though he was inspecting a piece of meat," she says.

"I knew what had just occurred was wrong," says Miller, who was offered a job and a contract. "I hated myself for allowing it to occur," she adds, but she chose to focus on the fact that she got the job, "even though it was clouded by feelings of blatant disrespect."

Andrea Tantaros, another former Fox News employee who made sexual harassment claims against Ailes, recently told New York magazine that in 2014 she was asked to do "the twirl" by him so he could look at her figure.

Public Enemy

It is not just colleagues or bosses that women journalists have to worry about: The nature of the job can put journalists in risky situations. Morgan Spiehs was an intern when she was grabbed outside the Salty Dog bar in southern Nebraska by a man who aggressively pursued her while she was on an assignment. A college sophomore at the time, she was working on a story about how the proposed Keystone XL pipeline would affect the village of Steele City, Nebraska (population: 61), located near the Kansas border.

"He just kept making very explicit comments about me coming over in front of his parents. He made all sorts of innuendos: My kids are away, I'm recently divorced, you won't regret this," Spiehs, a 23-year-old photographer, tells Newsweek. "I remember feeling very determined at the time to not let something like this get in the way of getting the photo. They were the only people at the bar, so I couldn't distance myself from this man at the time."

A storm was coming in, so Spiehs said she had to go home, and the man's family also got up to leave. As he got into the car with his parents, "he just realizes this is not going to happen, and he grabbed my butt so hard for two or three solid seconds while he said something in my ear," she says.

"I remember thinking at the time that happened that it didn't matter what job I had, it's a fact of life being a woman," says Spiehs. She didn't tell many people about the incident. By telling her story to Newsweek, "[it's] my chance to hopefully report, it in a way," she adds.

The Risks of Reporting Abroad

While U.S. workplaces have introduced legal protections against harassment, women journalists reporting abroad aren't always afforded the same levels of personal legal protection. Moreover, reporting from countries regularly accused of committing human rights abuses can be particularly dangerous for women.

In 2011, CBS journalist Lara Logan was sexually assaulted while covering protests in Cairo's Tahrir Square, in one of the most well-known incidents of a woman journalist being violently attacked while doing her job. CBS took the assault seriously and flew Logan out of Egypt. She spoke about the incident on 60 Minutes in 2011, and Jeff Fager, then-chairman of CBS News, said he hoped that would break the "code of silence" surrounding the risk of sexual assault faced by women journalists reporting overseas.

Amanda Mustard, 26, is a photojournalist who lived and worked in Egypt for three years. In Egypt, she says, reporting as a woman meant the constant threat of rape. She was followed home and assaulted on multiple occasions. "I would regularly walk around with a can of Coke in my hand in case I had to throw it at somebody," she says. She wore a stab vest to prevent unwanted touching and wore her belt inside out because it was then harder to remove.

Mustard developed a "serious physiological response to leaving the house," and the stress became so bad that she had a small stroke known as a transient ischemic attack. Even when she was in the hospital recommended to her for expatriates living in Egypt, the doctor flirted with her and told her she was just "being silly" despite the right side of her body going numb and her sudden inability to speak.

'You Don't Know How Bad It Has Been'

Mustard says there's "a real need for older female champions" to speak out about their experiences of sexual harassment, to let younger women know that they won't be blamed or perceived as weak. Carlson and Kelly, both established journalists, are a start, and earlier this month CNN anchor Carol Costello shared her own experience of harassment to refute claims made by Trump about his daughter.

"The two generations need to work together more," says Mustard. "It doesn't help anyone or change anything by pretending like it doesn't exist."

Leslie Bennetts, 66, was a journalist for 45 years. On the third day of her first job at a newspaper in Philadelphia, she says, she was in the elevator when a man grabbed her breasts and "jammed me up against the wall." That man was the book editor, and her boss's response when she told her was "Oh, that dirty old man." Harassment from sources was constant, Bennetts says. While it is a long-existing problem, the term "sexual harassment" wasn't recognized until about 40 years ago, after students at Cornell University coined it in 1975.

As younger women journalists seek more from their experienced counterparts, Bennetts says they need to understand "how bad a lot of this has been. If they haven't experienced this personally, they don't know it exists."

Bennetts, though, remains positive. Despite the stories and what she has endured as a woman in journalism, she has "a sense that the world is changing." For one, she was surprised by how decisively the Murdoch family acted in removing Ailes following the allegations against him.

"It's time for women to say we are absolutely not going to participate in these systems anymore. We are absolutely going to fight back, make it public, do whatever you have to do," she says. "For my generation, we owe it to our daughters."