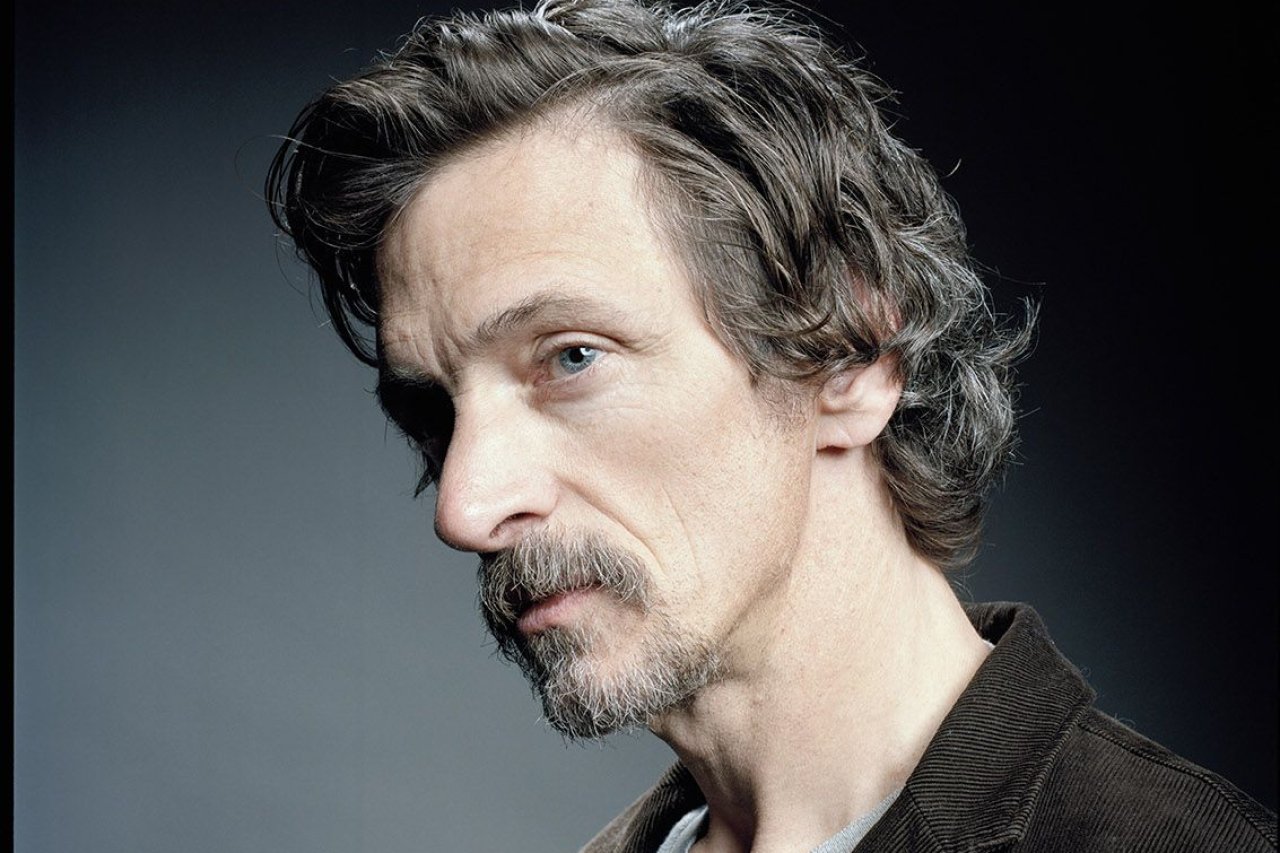

What's the opposite of overnight success? Sidling up to it? Or, to borrow from Joan Didion, slouching towards it? Perhaps the latter in the case of actor John Hawkes, whose slow ascent to stardom is thanks to the sort of characters that populate Didion's short stories—men and women who, Dan Wakefield once wrote, "are neither villainous nor glamorous, but alive and botched and often mournfully beautiful."

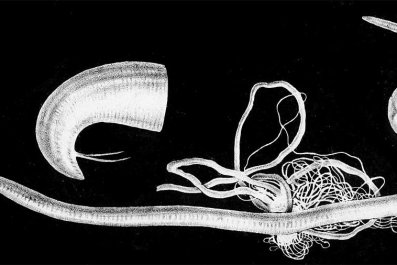

Hawkes was once described as a cross between Sean Penn and a Doonesbury character, and there's truth to that, but it doesn't capture the creased soulfulness that makes him ideal for film noir. Like Humphrey Bogart before him, one look at Hawkes and there's no questioning the shit show his character is inhabiting. In his latest film, the hard-boiled comedy Small Town Crime, Hawkes plays alcoholic ex-cop Mike Kendall, booted off the force for getting his partner and a bystander killed while policing under the influence. Long story short: After a typical all-nighter, Kendall discovers the body of a young woman lying by the road and becomes obsessed with finding the killer.

Kendall, by way of the increasingly grizzled 58-year-old Hawkes, is a lot more than cocky self-destruction, his face a furrowed plain of cunning, regret, humor and tenderness. "I have an uneasy relationship with my face," Hawkes admitted to Newsweek. "But you see yourself enough times, and you get past 'I have a big nose' or 'I hate the sound of my voice' to a place where you have peace and comfort with it. That was valuable, to stop obsessing too much."

It took roughly 20 years for Hawkes to ripen into something irresistible to filmmakers—a decade of mostly nameless roles: Driver of Teskey Truck, Pizza Boy No. 1, Groom, Cowboy. Hawkes was living in Austin, Texas, supplementing acting with work "in the straight world." When he moved to Los Angeles in 1996, "I did whatever crappy TV show I could," he said. "I meet young actors today who tell me they're already prepared to turn things down. I didn't have that luxury—I needed money. I've been a carpenter and a waiter," he says. "I liked those jobs, but I was better at acting, and the pay was better—usually. I did a lot of work for free: AFI and low-budget movies, student films. And I just kept going. I never had much ambition, I guess, but a great deal of passion."

Hawkes enjoyed the work, but he was perplexed by the reactions of casting agents in L.A. In Austin, he was considered "fairly normal," but Hollywood saw crazy. The parts he got were "psychos, nerds, psycho-nerds." One of those psycho-nerds was on a 1999 episode of The X-Files, "Milagro." He played a writer with a thing for human hearts and Agent Scully (Gillian Anderson). Legend has it that creator Chris Carter wrote the part for Hawkes. "Not that I'm aware of," said the actor, with characteristic modesty. He does remember the experience fondly.

It was another five years before he got the part that provided if not mainstream success then at least deeper interest: Sol Star, the Jewish business partner of Seth Bullock on the HBO series Deadwood. (Like any fan of the series, Hawkes is excited by talk of the show returning as a movie next fall.) Stardom, at least in the indie world, came in 2010, with his Oscar-nominated turn in Winter's Bone (the film that introduced the phenomenon that is Jennifer Lawrence), followed by two more Sundance Film Festival triumphs in a row: Martha Marcy May Marlene and The Sessions.

In Bone and Martha Marcy, he plays sinister characters in a Gothic rural America, but The Sessions—the story of the late poet Mark O'Brien, paralyzed since childhood from polio—was something altogether new. O'Brien had finally lost his virginity to a sex worker (played by Helen Hunt), and Hawkes could use only his face and voice. The entire performance was delivered on his back—excruciating for the actor (his body was painfully contorted for months) but curiously joyful and elevating for the audience, as Hawkes emphasized O'Brien's humor. "Not for cheap laughs but to find truth and absurdity and funny beauty wherever I could," he said at the time. "It's boring to watch someone wallow, even if he has every right to. It's more interesting to watch someone try to solve his problem."

Small Town Crime, written and directed by filmmaking brothers Ian and Eshom Nelms, came to him through his friend, Octavia Spencer, a co-star in several films. "She called and said, 'I've got a great script I want you to read. I won't tell you anything about it except that we play brother and sister,'" Hawkes laughed (Spencer is African-American). "I said, 'That sounds perfect.'"

It was. "A lot of times you read a script and you hope that it doesn't turn on itself as it goes, that it doesn't screw up by the last page," Hawkes said. "This one didn't."

He met with the Nelms brothers, who have made multiple shorts and features—low-budget festival favorites like Waffle Street—but nothing remotely mainstream. "They talked about films they liked—Die Hard and Clint Eastwood films, stuff that I wasn't super into," Hawkes said. "But they also spoke of wanting to entertain people, and that's not usually the thing that comes to mind for independent films." He chuckled. "There was some mistrust on my part: What do you mean you want to entertain people?"

The siblings clearly respect the tropes of pulp fiction while poking fun at them; Small Town is suspenseful and shot with bare-bones efficiency, but it's also wickedly funny. Hawkes had a smaller role, as an abusive husband, in a similarly savage comedy last year: Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, directed by Martin McDonagh. Hawkes took that job because he wanted to work with Frances McDormand, one of his favorite actors, and Sam Rockwell, an old friend. "Martin and the Nelms brothers get at dark comedy very differently, but they both emphasize surprise," Hawkes says. "That's something I always look for in a script."

Small Town Crime was shot on the flat, open roads of Utah, near Salt Lake City—ideal terrain for drunken speeding and careening. Kendall's bottle-cluttered vehicle is a matte-black muscle car, designed for street racing—as in no power steering. "I'm not even a car guy," he says. Don Shanks, a legendary stunt driver, let Hawkes do a lot of the driving, even when you can't see him in the shot. "But I have a driver's license, so that qualified me," said the actor."The car was a dangerous beast for sure, but it became a friend over time."

His equally treacherous human co-stars—in addition to Spencer and Anthony Anderson, who plays her good-natured husband and Hawkes's drinking buddy (particularly after Alcoholics Anonymous meetings)—include seasoned character actors Clifton Collins Jr., Don Harvey, Dale Dickey and the great Robert Forster. "He was one of my suggestions, I'm proud to say," says Hawkes.

Another suggestion: The opening and closing song, "Good Times," by the Animals. As a way into his characters, Hawkes imagines what they might listen to and read. "I'm a book addict—have been since I was a child. But Mike Kendall wasn't much of a reader, sadly—at least in my mind. Just because he was too busy fucking up his life," Hawkes said. "But I brought a lot of music to the set—the Ramones, Stooges, a band called Morphine; bands that have a kind of simplicity but also dangerousness. And when I was in the trailer getting dressed, I popped in the Animals and "Good Times" came on [with the refrain: 'When I think of all the good times that I've wasting having good time.'] I thought, That's Mike Kendall."

Simplicity and danger are a leitmotif for Hawkes: He's been a member of rock and punk bands since the early '80s, when the Minnesota-raised teenager landed in Austin. "I learned to play instruments in front of people, which was the norm back then." One of his bands, Meat Joy, featured three women, "an unusual lineup for its time."

Was the name inspired by the Meat Puppets? "No, but we did open for them at the Continental Club in Austin," he said. Meat Joy was found in a book about performance art, featuring a '60s piece by the artist Carolee Schneemann. "When you're in your early 20s, to break boundaries you look for things that seem crazy and wild and foreign," said Hawkes, whose band abstained from Schneemann's actural boundary-pushing, "involving nudity and chicken blood."

Hawkes never stopped playing and writing songs—one of them, "Bread and Buttered," is on the Winter's Bone soundtrack, and he sings an eerie ballad in Martha Marcy. His current group, Rodney and John, does "a form of rock," said Hawkes, who plays a lot of instruments but "gets around mostly on guitar." The idea behind Rodney and John, he said, was music with "a lot of grit and dirt and textures—jazz, punk, country—but that wasn't earsplitting."

Hawkes and his partner, Rodney Eastman, are working on a rock musical, his first long-form writing project since his 1996 one-man play, Nimrod Soul. It was inspired by a series of monologues he'd worked on with a successful theater company in Austin. "It ended up at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.," Hawkes said. "When I got to L.A. and didn't know anyone, had no money, I began to write my solo play."

It was a bid for casting directors (he played male and female characters) and a remarkably bold move for an unknown. Hawkes still seems surprised by the reviews—good enough that he traveled with it for a bit. "I didn't necessarily get a job directly from it," he said, "but I got more work because it made me a better and more confident actor.

"When you're younger," he added, "the tendency is to completely divorce yourself from any character you're playing. Over time, you realize you're losing a valuable asset, which is bringing your own experience to it."

Hawkes has never been interested in, as he put it, "being pushed down people's throats." He thinks of film as, first and foremost, a collaborative medium.

"My job is to serve the story. I haven't seen every movie I've done, but when I do, it's to enjoy how all the parts fit together—from makeup, wardrobe, editing, the other actors. That's how I learned." And often what he learned, he added, "was that I could have done better service. Samuel Beckett said, 'Fail again. Fail better.'" Hawkes laughed. "That's been very helpful."'

Small Town Crime will open in theaters on January 19. It is now available exclusively on DirectTV.