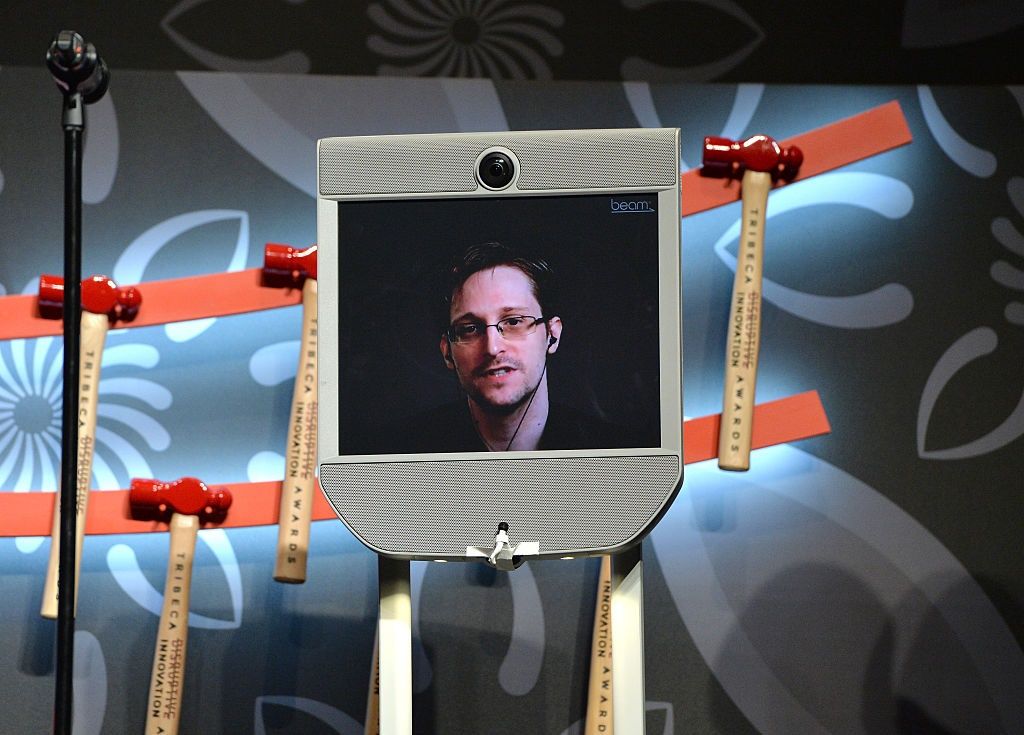

No issue about Edward Snowden has been more vexing than the question of his relationship with the Russians. Or to put a more fine point on it: Whether he's now, or has ever been, a Russian agent.

Unfortunately, the House Intelligence Committee's vague report Thursday won't help answer that question. Not only that, its wording smacks of the kind of language that the rabid Red hunters of the House Committee on Unamerican Activities pinned on liberal and leftist writers and actors in the worst days of the 1950s.

RELATED: Snowden in Contact With Russian Intelligence, House Report Claims

Snowden, the panel said Thursday in its newly declassified report (which still includes substantial deletions) "has had, and continues to have, contact with Russian intelligence services."

Well, of course he has. If a Russian counterpart of Snowden suddenly washed up on America's doorstep with thumb drives full of purloined files from inside Moscow's equivalent of the NSA, U.S. intelligence officials would elbowing each other to get to him. Indeed, his submission to a thorough debriefing would be the price of his admission here. Next would come a sustained effort to turn him from self-styled whistleblower to an intelligence asset.

But on the question of whether the Russians succeeded with Snowden, the intelligence committee's report adds more heat than light. Snowden's chief lawyer, Ben Wizner, was instantly contemptuous of it, quickly tweeting that it was "petulant nonsense."

Which is not to say there aren't important, unresolved questions about the relationship between the Russians and the former NSA contractor. Edward Jay Epstein, a journalist who has written deeply on intelligence conspiracies for many years, lays out an intriguing chain of events on that issue in a provocative new book, How America Lost Its Secrets: Edward Snowden, the Man and the Secrets.

On September 23, 2013, he recounts, Edward Snowden's Russian lawyer gave a broadcast interview in Moscow. The radio host, Sophie Shevardnadze, was no ordinary interviewer: Her grandfather was the late Eduard Shevardnadze, the last foreign minister of the Soviet Union and a member of its ruling Politburo. Nor was her guest an ordinary lawyer: The silver-haired Anatoly Kucherena, 56, had a number of high profile clients, including Viktor Yanukovych, the Moscow-backed fugitive former president of Ukraine. And Kucherena, a political supporter of Russian President Vladimir Putin, was a Kremlin insider; he sat on a parliamentary board that theoretically oversees the FSB, the all-powerful successor to the Soviet-era KGB intelligence service.

In other words, Kucherena was wired to Russian intelligence, and Putin likely had him on speed-dial after Snowden made contact with the Russian consulate in Hong Kong. It was Kucherena who persuaded the former NSA contractor to "abandon his appeals for political asylum in more than 20 other countries, arguing that they had no legal standing while he remained on Russian soil," according to an interview Kucherena gave to Steven Lee Myers of The New York Times. Instead, Kucherena helped Snowden file for temporary refuge. Eventually, of course, the ultimate fate of the "defector," as Moscow privately saw him while lavishing praise on him as a whistleblower, would be determined personally by Putin.

Snowden had arrived in Moscow with a laptop. But he insisted that he would never turn over any of his stolen documents to Russia, America's number one adversary. "No intelligence service—not even our own— has the capacity to compromise the secrets I continue to protect," he wrote to the former Senator Gordon Humphrey, as recounted by Epstein. "I cannot be coerced into revealing that information, even under torture."

But in her interview with Snowden's lawyer, Shevardnadze was eager to know whether his client brought gifts with him to Moscow.

"So he does have some materials that haven't been made public yet?" she asked.

"Certainly," Kucherina replied.

Shevardnadze then asked "the next logical question," as Epstein puts it: "Why did Russia get involved in this whole thing if they got nothing out of it?"

And Kucherena replied: "Snowden spent quite a few years working for the CIA. We haven't fully realized yet the importance of his revelations."

In 2015, Epstein interviewed Kucherena in Moscow. He told the author that "all the reports" on Snowden were turned over to him by "Russian authorities" soon after he arrived in Moscow. "I had all of Snowden's statements," Kucherena said. Epstein concluded that the lawyer "presumably knew what Snowden had told the Russian security services."

Secrets have continued to spill from Snowden's archives, long after he fled in the summer of 2013––and few of them related to U.S. "domestic spying" programs. He has been a font for reports on the NSA's foreign intelligence gathering operations, from its "tailored access" hacking operations targeting foreign adversaries, to its global sweep of private text messages, to its intercept of "all phone calls—including both metadata and content—inside the Bahamas." His revelations of the NSA's relationships with eavesdropping services of the U.K., Germany, Israel, France and other allies, which had nothing to do with questionable domestic spying by the NSA, served mainly to provoke tension and discord between the U.S. and its friends.

All of which suggests that Snowden is paying a price for his gilded cage in Moscow. And to think otherwise is naîve, intelligence veterans on both sides of the Cold War say.

Shortly after Snowden popped up in Moscow in 2013, I called up former KGB General Oleg Kalugin, who headed his service's operations against North America before fleeing Moscow as the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. As young man in the 1960s and 1970s, the genial Kalugin was such a good recruiter of American spies that he'd quickly been promoted to KGB "rezident," or station chief, in Washington, D.C.

I asked him how Putin's spy service would have treated Snowden when he showed up at the Russian consulate in Hong Kong.

"They would debrief him, make him comfortable, see if he's honest, and then they would [tell Moscow] that we think he deserves attention and may be useful."

Once he was paroled into Russia, Kalugin told me, "they will proceed into areas that they are not well-informed on. And then they will milk him for new information."

What if he resists and says he doesn't want to be a Russian agent—I'm doing this for idealistic reasons—I asked. Then what do you do?

"Well, you say, we are also doing this for idealistic reasons. They will find some response to make him comfortable."

"Inevitably," Kalugin said, they would put pressure on Snowden to unlock more secrets. Nothing intense. Snowden would know who's paying his rent, and that Putin could FedEx him back to America if it served his purposes.

"If he wants to continue to be treated well, then he has to tell the truth," the wily old spymaster said. "If he starts avoiding them, then they say, 'Okay, well, goodbye, thank you for what you did, but we are not interested in you anymore. You're out of Russia.'"

Would a time come, I asked, when Snowden has to make such a choice?

"Yes, absolutely, exactly," Kalugin said.

Snowden rejects such scenarios. And he called the intelligence committee's report, which dismisses his claim to be a whistleblower acting in America's interests, "rifled with obvious falsehoods." In a subsequent tweet, he mocked its absence of evidence for its charge that he acted as a Russian agent. "After three years of investigation and millions of dollars," he said, "they can present no evidence of harmful intent, foreign influence, or harm. Wow."

Wow is right. There is an absence of evidence. On the question of Snowden's collaboration with Russian intelligence, the committee's report merely amounts to a prosecutor's opening statement, not a closing argument backed by hard facts. And, as in some of the great, enduring spy mysteries of the Cold War, decades may pass before we know something resembling the truth.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.