Jimmy Breslin wasn't happy. He was on his way to meet with an editor in the Condé Nast Building in Times Square when the guards at the security desk stopped him and asked him where he was going. "I found him at the desk, eyebrows knitted together in consternation. I could tell right off the bat that something was going wrong," says Megan Angelo, who was an editorial assistant at Condé Nast Portfolio in 2007 and the person sent down to the lobby to retrieve the fuming Breslin.

The lobby of the old Condé Nast Building felt like a cathedral and was always solemnly silent as very important New Yorker writers and Vogue assistants in designer dresses walked quickly through the glass doors. "Jimmy Breslin had no time for that fake reverence," Angelo, now a freelance writer with bylines in Glamour and The New York Times, tells Newsweek. When one of the young guards dared to ask Breslin again whether he had any identification at all, the newspaper legend barked so loudly that everyone in the lobby turned to look: "Yeah, my face!"

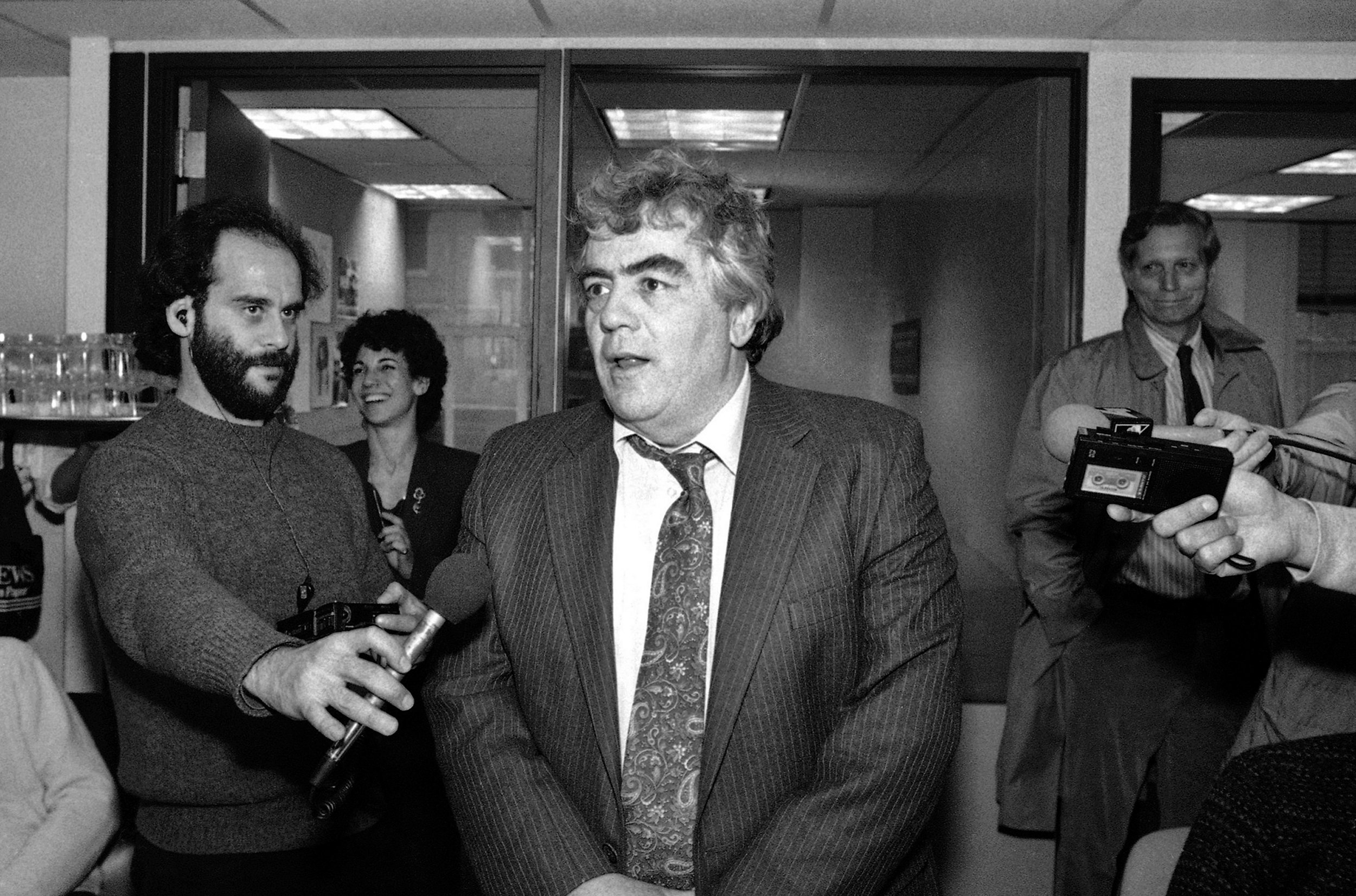

Breslin died Sunday at his home in Manhattan. His New York Times obituary described him as "the New York City newspaper columnist and best-selling author who leveled the powerful and elevated the powerless for more than 50 years with brick-hard words and a jagged-glass wit." Upon hearing of his death, New York City reporters and editors who had worked with Pulitzer winner began to trade stories of Breslin being Breslin, whether that was in the lobby of the Condé Nast building, over the phone or in a backroom at a Queens pastrami joint.

"I was covering the Howard Beach racial murder trial [in the late 1980s] for the [Daily] News, and one day near the end Breslin arrived all rumpled and blustery. Naturally he said, 'What's doin'?'" recalled Stu Marques, a longtime New York City reporter and editor, in an email to Newsweek that detailed the writer's infamous work ethic. "A couple hours later, I wandered into the Pastrami King across Queens Boulevard and was standing near the back when I heard what sounded like a decidedly one-sided Breslin conversation in the adjoining room."

Marques quietly pushed open the door to the next room and saw Breslin reading aloud his column about the trial for the next day's paper. "He's sitting down hunched over, he's got some paper in front of him, and he's talking, he keeps going over a couple of sentences," Marques tells Newsweek in a phone interview. When Breslin was wrapping up, Marques closed the door and quietly walked away. "Next day he asked me if I'd seen his column. I said I heard it yesterday in Pastrami King," Marques says. "He laughed."

Breslin was also notorious for his endless phone calls, always sparring and searching for a story. When longtime city journalist Jerry Schmetterer was the police bureau chief and later the metro editor for the News, Breslin would call him every morning as part of his drive to sniff out his next column. "He would call and ask, 'What's doing?'" Schmetterer says. "You could tell him they just found a body on 42nd and Fifth, and he'd want to know everything you had."

Schmetterer says Breslin called him most mornings in the late 1970s, which was around the time Breslin got a letter from the then-at-large serial killer David Berkowitz, also known as the Son of Sam. His young son would answer the phone when Schmetterer was shaving or getting dressed and would start talking with Breslin, who seemed happy to spend his morning chatting with an 8-year-old.

"Every second he breathed, it was about being a newspaper reporter. That was his life. I admired him for it," says Schmetterer, who went on to say that once Breslin's phone calls informed him about a crime or event, he always showed up at the scene. "The great thing about him was he actually went. He used his feet. He used up his shoe leather. He was a hardworking reporter."

I was lucky enough to be on the receiving end of a probing Breslin call once. When I covered Brooklyn Supreme Court for the New York Post about three years ago, I answered the phone one afternoon to hear a gravelly voice asking for the retired NYPD captain turned journalist who reported on that court before me, Billy Gorta. Billy doesn't work here anymore, I said. Who's this?

This is Jimmy Breslin, he told me. Oh, wow, I said. When I first moved to New York and was trying to get a job reporting, I bought a book of his columns at the Strand Bookstore and read it in Central Park, marveling at the strength and wit in his writing. I told him that, but he didn't care much. His mind seemed to wander for a moment. There was silence on the line. But then he snapped back into his longtime habit of pulling out his next story: "So what's doing?"

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Josh Saul is a senior writer at Newsweek reporting on crime and courts. He previously worked for the New York ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.