Leonard Berney is sitting in his apartment when we speak, gazing out at the South Atlantic sea from his balcony. Docked at the Namibian coastal town of Lüderitz, he is soon to embark on a 300-mile journey to Walvis Bay up the coast .

The 95-year-old former British army major owns one of the 165 apartments on The World residential ship – a huge luxury yacht which circumnavigates the globe every year. Currently he's just over three months into his 2015 trip, a journey which will take him from Singapore, through Europe, down the west coast of South America, culminating in an Antarctic expedition. It's hard to think of a place further removed from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, which Leonard helped to liberate 70 years ago today.

"My first impressions were shock and awe, as you say," Leonard says. "The sights and the sounds were a complete shock, we weren't prepared for it, we didn't expect it, I have never seen anything like it and neither has anyone else."

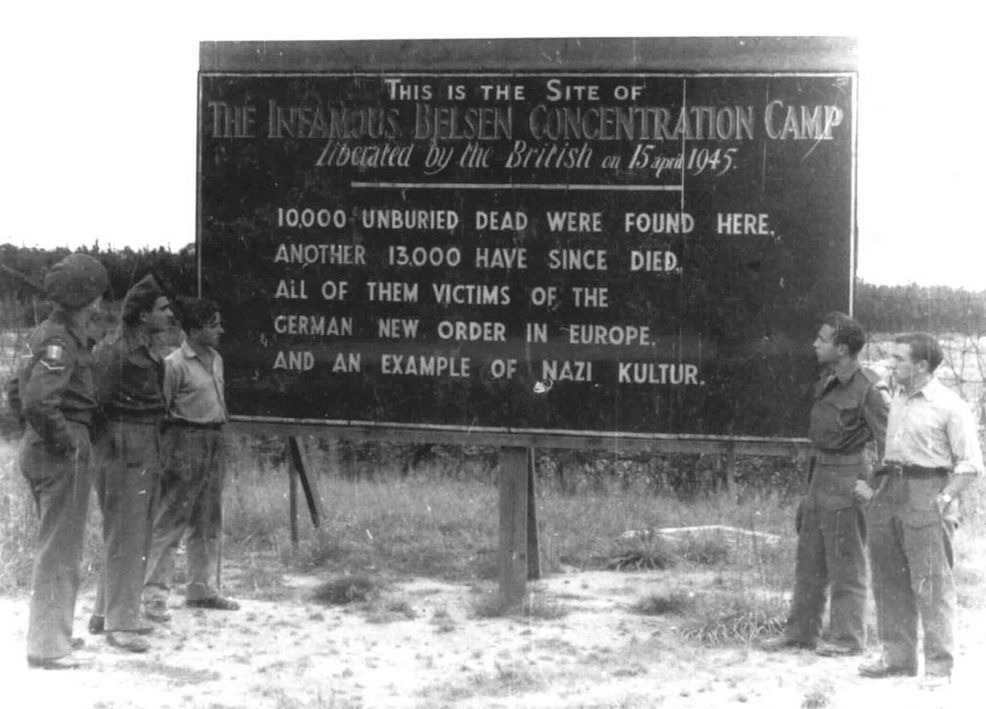

Unlike Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen was not formally considered an "extermination camp" as it did not house gas chambers, but it was a death camp nonetheless. The lack of food, shelter and medicine led to the deaths of thousands of inmates who contracted diseases such as typhus or tuberculosis. When the British troops liberated the camp there was no running water available. It's estimated that 70,000 people died in Bergen-Belsen, with 60,000 prisoners still in the camp when the British Allied 21st Army Group arrived.

Leonard had just turned 25 at the time of the liberation and he says many of the soldiers he was with were younger, many in their late teens. "Of course it was overwhelming," he says, "I mean, where do you start? There were just a few of us and tens of thousands of them in a very bad state, thousands of dead, and people were dying at a rate of about 500 a day – what do you do?"

The camp was run by the notorious Josef Kramer, otherwise known at "The Beast of Belsen", a much feared Nazi who moved quickly through the ranks and who had been in charge of the gas chambers at Auschwitz. While many of the camp's guards fled before the British soldiers arrived, Kramer willingly remained and even offered to show the troops around the camp. "He was surprised we were horrified," Leonard explains. "The people in the camps were regarded as sub-human. Untermensch is the German phrase."

The troops established the water supply and sourced food from the surrounding area, working to evacuate the inmates, who were dying at a rate of 500 a day, to a new displaced persons camp they set up down the road.

"It was unimaginable," Leonard says, "but we couldn't mope around. We just had to get on with it and that's what we did."

"I had flashbacks of the scenes for the next couple of years about it. Memories come back but I had to get on with my life and living. I got over it. I think quite a lot of people didn't, apparently," he says, almost in passing.

One woman who certainly still remembers Leonard is Nanette Konig-Blitz, a Dutch Jew. Nanette was 14 years old when she first arrived in Bergen-Belsen. By the time she left the camp she was the only remaining survivor of her immediate family.

She's now 85 and has lived in São Paulo in Brazil since 1953, although she Skypes me from a hotel room in New York – she explains that she and her husband John are visiting relatives.

"When Major Berney first met me in Belsen, he thought I was of British descent because I could speak English quite well," Nanette explains. She describes how she briefly helped him as a translator in the camp before she became too ill with typhus. "He wrote letters to my family in England telling them I was still alive. I was flown back to Holland with the RAF and I believe he was a factor in that."

(Leonard underplays the event when I ask: "She says I saved her life, but I saved a lot of people's lives – it wasn't personal.")

Nanette has spoken often about her experiences in the camp, speaking at schools and conferences in an effort to maintain the memory of the Holocaust, which she believes is in danger of slipping away.

Brought up in a normal, middle-class family before the war, she maintains that there was latent anti-Semitism in Holland even before the Nazis arrived. "The Jews were always discriminated against, it's just that anti-Semitism came to the foreground when the Nazis arrived."

Evicted from their home before being moved into the ghetto, Nanette's family arrived in Belsen in February 1944. Initially, they were registered on the Palestine list which meant they could be exchanged for prisoners of war if necessary. Nanette explains that Heinrich Himmler "kept a certain stock of Jews in Bergen Belsen for this in the 'star camp'. That was our position, but I know of just one transport that went to Palestine".

"After my father died in November 1944, our so called privilege, which was not a privilege, ended." Her brother was shot on 4 December and her mother was sent to the salt mines in Magdeburg the next day. Nanette later discovered she had died on a transportation train on 10 April 1945, just months before the end of the war.

Following the complete disintegration of her family, Nanette managed to survive for four more months in Bergen-Belsen. She recalls seeing her old classmate Anne Frank in the camp. "She was completely depleted and couldn't withstand the typhus," Nanette recalls. "I remember somebody said that if she'd known her father was alive, she would have survived, but I assure you that she would not have survived because you couldn't survive through will power. The typhus hit her and there was nothing left of her, she couldn't withstand it."

After the liberation, Nanette briefly returned to Holland before travelling to the UK to join family there. Would she ever think of going back to her country of birth? "I wouldn't go back to Holland. There's nothing left there. My family ask me that sometimes, but when I walk through the neighbourhood where I used to live I can stay for two weeks and that's it. When I pass the door of my old home it's very traumatic."

Leonard and Nanette have not seen each other since 1949 when Leonard visited her in London, but the lasting effect of the horrific experiences of their earlier lives is clear.

While Leonard insists he did not let the sights of Belsen blight his life, his opinion of humanity certainly seems affected. "Unfortunately, the human race is afflicted with the disease of genocide and it goes on. It's going on right now."

Nanette agrees: "People stand up and say 'Never again', and I say 'Never again what'? The Holocaust was industrial genocide, but there have been many genocides since, and they continue to go on."

Leonard only began to speak about his experiences a few years ago, prompted by people trying to deny the Holocaust, but he fears for the future. "I think the memory will fade, two or three generations on. In the mean time, I'm doing what I can, and others are doing what they can, to educate the young people about what can happen, what did happen and what can happen again."

Leonard Berney's book about the liberation of Bergen-Belsen is out now.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Lucy is the deputy news editor for Newsweek Europe. Twitter: @DraperLucy

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.