It's the original guide to "everything illegal," from pot loaf and hash cookies to tear gas, dynamite, and TNT. There are frank tips on demolition, surveillance, sabotage, and the gorier parts of hand-to-hand combat, including how to behead a man with piano wire and make a knife "slip off the rib cage and penetrate the heart." In the introduction, the then-teenage author makes clear his wish that the book be of more than just theoretical use. "I hold a sincere hope that it may stir some stagnant brain cells into action," he wrote.

William Powell, author of The Anarchist Cookbook, succeeded all too well. His slim, 160-page volume democratized the nuts and bolts of terror. Published in 1971, it would sell more than 2 million copies worldwide and influence dozens of malcontents, mischief makers, and killers. Police have linked it to the Croatian radicals who bombed Grand Central Terminal and hijacked a TWA flight in 1976; the Puerto Rican separatists who bombed FBI headquarters in 1981; Thomas Spinks, who led a group that bombed at least 10 American abortion clinics in the mid-1980s; and the 2005 London public-transport bombers.

Just last spring, after a father-son team of British white supremacists drew on the book to make a jar of ricin, a London judge joined police in calling for a ban on the title and the many copycat volumes it has inspired. But retailers refused, and the book's Arizona-based publisher, which acquired the rights in 2001, declined to comment. So the work lives on, and so does its author. Just not in the way you might expect.

Powell, now 61 years old, long ago renounced the best-selling terrorist bible he penned. He left the country in 1979, bouncing around the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, working as a teacher and administrator in a series of State Department–backed private schools. He wrote more books, about pedagogy and professional development. And he gained a reputation for—wait for it—conflict resolution.

Powell has not spoken publicly about his role in fostering a generation of anarchic rebellion. Until now. In an exclusive interview with NEWSWEEK, he talked about the origins of the Cookbook, his reinvention as a teacher of diplomats' children, and how he processes the unseemly acts that are tied to his name. Taken together with a batch of recently released FBI records on Powell's case—including more than a hundred pages of civilian letters, internal memos, and intelligence reports discussing the book's dangers—his comments tell the story of a lost chapter in the history of American radicalism, one that still resonates wherever established order is under attack today.

"It's part of who I am," says Powell of the Cookbook. "In the context of 1969 and the Vietnam War and a wide-eyed 19-year-old," he adds, "some of the sentiments contained in it make sense." But in a subsequent conversation, he takes a step back. "I'm sorry that it has been used by people for violent purposes."

In 1969 Powell was living in a tenement in lower Manhattan. Vietnam vets bought and sold drugs in nearby Tompkins Square Park. Outside his door, as war dragged on, the glow of the Summer of Love was wearing off. The peaceniks were beginning to get violent. In the course of 1968 and 1969 alone, there were well over a hundred politically inspired bombings, not including arson and vandalism, according to The Sixties, a history of the era by former activist Todd Gitlin.

Powell had come to New York from Westchester County, dropping out of high school and fleeing to the city the first chance he got. The son of a United Nations press officer, he spent his early boyhood in the leafy London suburb of Harrow, enrolled in a private school where 8-year-olds studied Latin and Greek and were made to recite Scripture from memory. If they faltered, they were beaten. "I was caned fairly regularly," he recalls. He moved back to America as a middle-schooler, sticking out because of his British accent and impatient with school.

Settling in Alphabet City in an apartment "with the proverbial bathtub in the kitchen," Powell became part owner of an off-off-Broadway theater, more interested in the poetry of Arthur Rimbaud than radical movements. But he wanted to become a writer, and he got a letter—one that threatened to tax his personal liberty and force him into war. The arrival of a draft card in the mail "made me very angry," he recalls. Suddenly, his research for a book took a decidedly political turn.

Between 1968 and 1970, Powell devoured the "U.S. Combat Bookshelf" in the New York Public Library, reading decommissioned government manuals. He supplemented those with Boy Scout guidebooks, electronics catalogs, and a stack of obscure insurrectionist pamphlets, including Abbie Hoffman's F--k the System. The result—produced longhand at home on legal pads—was a brisk volume infused with the first-person authority of someone who had deep experience doing drugs and toppling governments. "There are basically two methods of booby-trapping pipes … Explosions can be a really thrilling and satisfying experience … Banana skins really do contain a small quantity of Musa Sapientum Bananadine."

The problem—besides the fact that banana skin is not, alas, a psychedelic—is that Powell had little personal experience with the activities that he was expounding upon. His guerrilla tactics and bomb-making recipes were "for the most part accurate," as the FBI's own laboratory later concluded. But his voice was the invention of an aspiring novelist, and so were most of his anecdotes. He never drove a hot-wired car to Miami, made LSD in his kitchen, or fed cops a fake name when busted at an antiwar demonstration, as the book suggests. In fact, Powell's only appearance before a judge involved his theater, when Paramount Pictures sued for an illegal run of The Little Prince. (Powell closed the show, and the suit disappeared.)

The book, however, did not. As he was finishing the writing, he took the SATs and applied to Windham College, a now-defunct liberal-arts school in Vermont, where enrollment tripled with kids hoping to sit out the war with an "education" deferral. Powell then sent his manuscript—titled The Anarchist Cookbook for the simple reason that it contained recipes for would-be hell-raisers—to perhaps the most daring publisher of the time. Lyle Stuart had just blown the mind of square America with The Sensuous Woman, which purported to be the first sexual how-to book written by a lady, for ladies, and he liked Powell's offering right away. "No one else did," Stuart told an interviewer in 1978, "and of course no other publisher would touch it." In other words, a perfect match. It was "published verbatim," Powell adds.

The Cookbook debuted in mid-January 1971. Almost immediately, as the FBI's recently released records show, letters poured into the bureau from citizen snoops around the country. "This is not a cookbook!" wrote George Kellog of Glendale, Calif. "Why is this allowed to happen!!!" added Earl C. Levering, who didn't bother with a return address. Joseph Singleton of Titusville, Fla., simply scrawled his message on a news clipping: "Danger!" he wrote to the office of director J. Edgar Hoover. "What are you doing about this???"

Officially, the answer was nothing. Hoover (or his PR team) responded with reassurances that "I share your concern about this matter," but "the FBI has no control over material published through the mass media." Internally, however, the teletype machine came alive. "Urgent" correspondence flew between senior members of the White House, the Department of Justice, and the FBI, including President Nixon's lawyer, John Dean (who later did time for the Watergate cover-up), and Hoover's associate director, Mark Felt (later revealed as the informant known as Deep Throat). The conclusion: this is "a manual for revolutionary extremists," and "the effects on a civilized society could be devastating."

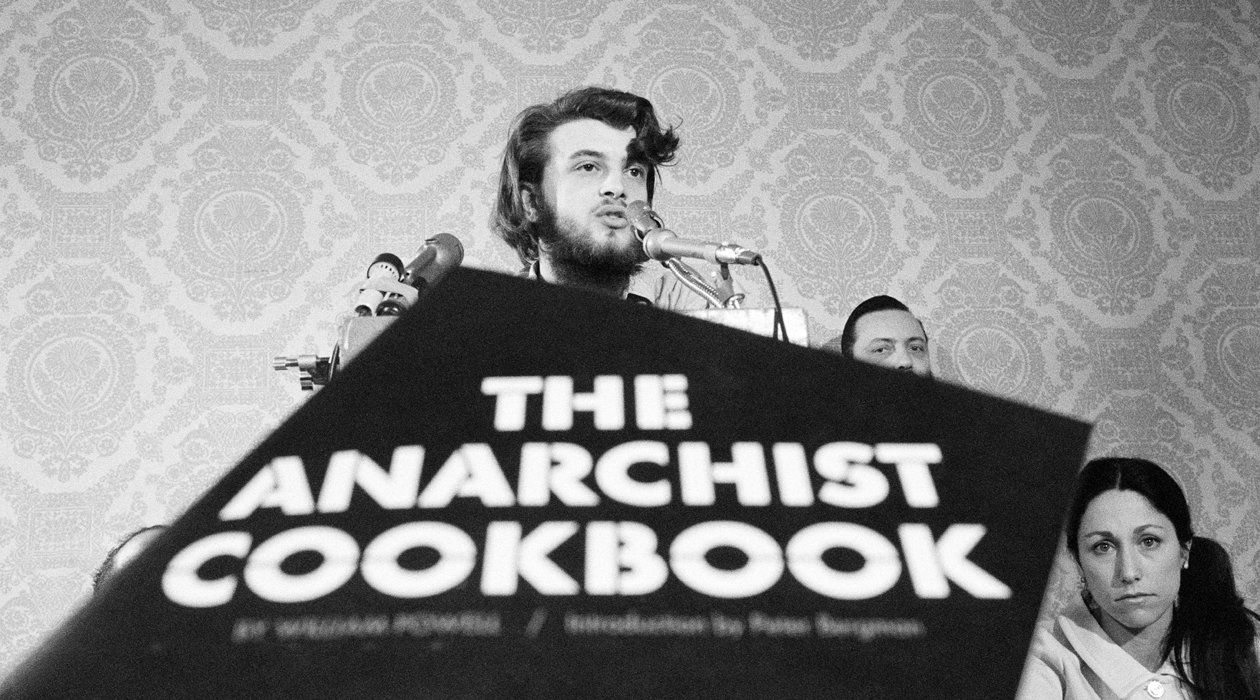

The effect on Powell was devastating, too. In the 12 months after the book was published, bombings increased to an average of five a day, according to FBI data. Citizens who blamed Powell stuffed his Vermont mailbox with death threats. Anarchists weren't happy, either, accusing him of war profiteering, and setting off stink bombs at his only press conference in New York. The FBI never bothered Powell personally (deciding that he would leverage it for publicity). But they questioned his father and his father's colleagues at the U.N., and they tracked which stores were selling the book. He drew increasing publicity—NEWSWEEK and others profiled him and attacked his work—but he shrank from the limelight. "I can't say I enjoyed the notoriety," he says, "and I didn't expect it." Amid it all, Powell himself soured on the book, purging his home of copies and declining to discuss it with friends. "I didn't anticipate the ramifications," Powell says. "I don't think I was as emotionally intelligent as I might be now."

Powell dropped out—way out. He signed on as chief timekeeper on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. He volunteered as an English instructor in a home for disturbed boys. In 1975 he moved back into his parents' house in Westchester, volunteering as a special-ed teacher, earning a master's degree in English, and eventually landing a paid teaching job upstate. He met the woman who would become his wife. And he tried to forget about the destructive cultural force that bore his name. "Actually, the book had stopped selling and the royalties at this point were negligible," he says, unsure why sales ever picked up again. "I just assumed that the book would go out of print."

Powell reinvented himself as an educator on the international stage. He lectured at the University of Riyadh in Saudi Arabia (he wrote a history of the royal family that got him banned from the kingdom), and rose through the ranks to attain top positions in schools packed with children of the international elite in Dar es Salaam, Jakarta, and Kuala Lumpur. He was commissioned to write three books by the Office of Overseas Schools. But even as his star ascended, he never completely escaped his past.

In 1991, interviewing to become headmaster at a Tanzanian school, a member of the parent board asked Powell how to make a Molotov cocktail. Powell swallowed hard. But the chairman, who knew about the Cookbook, had his back. He dismissed the work "as a youthful folly or symbol of protest," according to the school's official history. Powell got the job. A similar incident occurred two years later; on the strength of his record, Powell again prevailed.

The spread of the Internet only triggered more questions from students and colleagues. A senior asked Powell to sign a copy of the Cookbook on his graduation day. Then Al Qaeda bombed the U.S. Embassy in Tanzania, and another in Nairobi. The Anarchist Cookbook played no known role in the attacks, but anonymous mudslinging ensued, with parents warning the board of "a secret organization within the school." Powell resigned the following year (not, he says, because of pressure). But he struggled to land another job.

He decided to go on the offensive—in a modest way. In the hopes of preempting critics and relieving "the discomfort of pretending it's not there," Powell added reference to the book to his résumé. He also posted an eight-paragraph note on the book's Amazon.com sales page, calling it "a misguided and potentially dangerous publication" and expressing his wish that the book be taken out of print. Yet his views don't hold any sway: the rights belong to the publisher, and always have, so Powell has been a helpless observer, forced to watch his work inspire new generations of evildoers.

"I don't like to think that I contributed to people being killed," he says—taking no responsibility for the deeds associated with the book (because "I did not do them"). He believes that serious terrorists would have found a way to wreak havoc without him. Friends, family, and colleagues obviously agree. (A State Department spokesperson says they've "known for several years" about Powell's past.)

Earlier this month, almost 40 years to the day after he became a best-selling author, Powell flew from Beijing, where he and his Chinese wife often work as education consultants, to San Francisco. There, in the Grand Ballroom of the downtown Hyatt, some 500 members of the Association for the Advancement of International Education gathered to give Powell a lifetime-achievement award. Powell and his wife are "both highly, highly respected," says Elsa Lamb, executive director of the group. "He's awesome!" adds Toni Mullen, an American-born alumni director at one of the schools where Powell served as headmaster. The day after he received his award, the FBI released documents containing an honor far sweeter: a memo clearing Powell's name. "We have studied the contents of the book itself, as well as the information contained in the Bureau reports," the 1971 memo states, and "we have concluded that the book does not urge 'forcible resistance to any law of the United States.'?" There is also "insufficient evidence that the author or anyone else used the book as a guide," and "we cannot establish necessary intent." For these reasons, "no further action is in order."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.