In late July, a 21-year-old online-gaming addict was found dead in his home in Inchon, South Korea. He'd played intensely since graduating from high school, rarely sleeping or leaving his room, according to family members. Two months prior to his death, he'd begun complaining of difficulty breathing but had refused to seek medical attention.

The Inchon death hasn't been the only sensational gaming case to scare South Korea. In 2005 a 28-year-old man collapsed and died from organ failure after playing for 50 hours straight. He had apparently just lost his job because of his online-gaming habit. The most high-profile case happened in 2009. A married couple from Suwon immersed themselves in a game where they took care of a virtual infant while their real baby starved to death. The couple was charged with negligent homicide and sentenced to two years in prison. (The wife's sentence was suspended due to her being pregnant again.)

South Korean authorities think that these fatalities are part of a much larger national problem: gaming addiction. Over the past year, two big surveys—one by Seoul's National Information Society Agency, the other by Korea's Ministry of Gender Equality and Family—found that more than one in 10 Korean adolescents are at high risk for Internet addiction and that one in 20 are already seriously addicted. Next month the government is getting tough on the problem: a Gaming Shutdown Law, also dubbed the Cinderella Law, is set to go into effect. The law would prevent underage gamers from playing online, whether via PCs, handheld device, or in "PC bangs"—Korean gaming arcades—from midnight until 6 a.m. Just how the government will enforce the law is a subject of debate. One possibility would see minors registering their national identification cards online, a requirement already enforced in China. But in China, kids simply use stolen ID numbers, and many suspect hard-core Korean gamers will do the same.

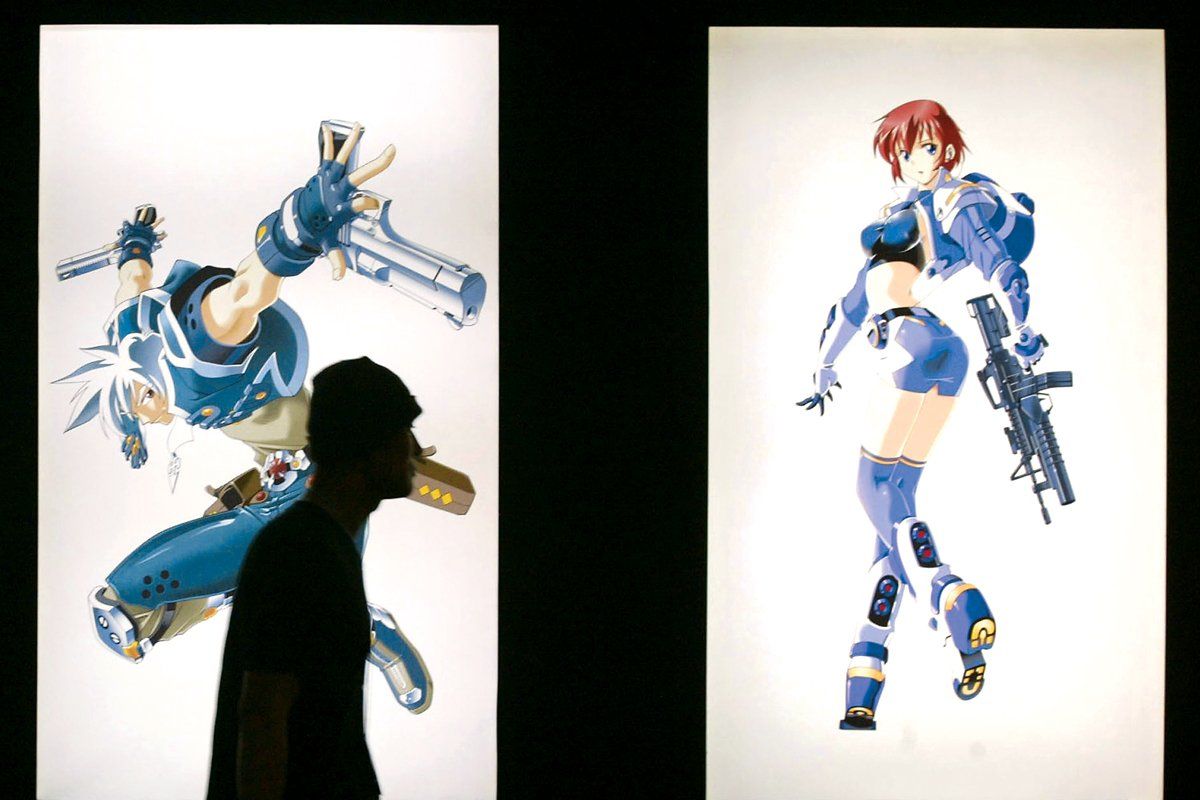

Jung Hwan-jeon sees hard-core gamers every week at his job at a PC bang in Seoul's Sogang University district. At the arcade—typically a single smoke-filled room with 20 computers, a vending machine selling coffee and soda, and a snack bar stocked with instant ramen—patrons sit side by side and play for hours on realistic bloody avatar games such as Halo, StarCraft, and TERA. Once, Jung says, a customer played StarCraft, one of South Korea's oldest and most popular games, for 85 hours without stopping. "On the third day," says Jung, "he ran out of money. He gave me his cellphone as a deposit and never came back."

Jung's tale is familiar in South Korea, the most-wired country in the world. Schoolchildren face extreme academic pressure, and they have few after-school activities to participate in—so online gaming is one of the few places where the average student can excel or escape. And superstars have been born from the gaming world. Players like Jung Myung-hoon and Yo Hwan-lim earn close to $400,000 a year battling it out in professional StarCraft leagues (one of 10 major gaming leagues in the country). They are watched by millions of fans in competitions broadcast by two of Korea's major TV channels. The gaming leagues are sponsored by big corporations such as SK Telecom and Samsung. The popularity of the competitions has spawned the World Cyber Games, the Olympics of the gaming world—held this year in Busan. South Korea has won the grand-champion title for the past three years.

In a nation where more than half of the nearly 50 million people play online games, the industry has become a cash cow. In 2008 the online-gaming industry earned $1.1 billion in exports, according to the Ministry of Culture—more than half of the country's entire overseas revenue. Games like StarCraft, first published in 1998, have sold 11 million copies worldwide (4.5 million in South Korea alone). Understandably, it's going to be difficult to regulate such a massive industry. But the government is intent upon trying. In 2002 it opened one of the first treatment centers for Internet addiction. Game companies, such as NCsoft, based in Seoul, also finance private counseling centers and hotlines. Today, hundreds of hospitals and clinics have installed government-subsidized programs to treat gaming addiction, such as the Save Brain Clinic, opened in 2011 at Gongju National Hospital, 120 kilometers outside Seoul, specializing in treating the disease.

Dr. Jaewon Lee, the program's director, has seen a range of addictive behaviors among young gamers. "One kind of person is afraid of social interactions, so they talk with online-game users. Other people seek an omnipotent feeling, gaining more power over others." Certain types of online games—multiplayer role-playing games, and first-person shooter games—are considered the most addictive. Whether these games draw in kids who are already "socially awkward loners," as one psychiatrist puts it, or whether they enforce such tendencies, the result is the same: "It's very hard for [addicts] to be with other people when they're offline." The clinic treats patients with a mix of medication, therapy, and, in extreme cases, magnetic stimulation of the frontal cortex, which is hyperfunctional in gaming addicts—much like that of cocaine addicts.

Joo Mi-bae, a representative for the Korean Youth Counseling Institute's Internet addiction group, says that while the shutdown law isn't perfect, many parents appreciate the government's intervention efforts. Adults work late and are often unable to take the necessary steps to control their children's Internet or online-gaming behavior. And maybe even some young gamers themselves will appreciate it. Kyong Min-kim, a student majoring in economics in Seoul, says, "One time five summers ago, I played World of Warcraft five hours a day ... but then I thought, that kind of life isn't really good for me. So I just quit."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.