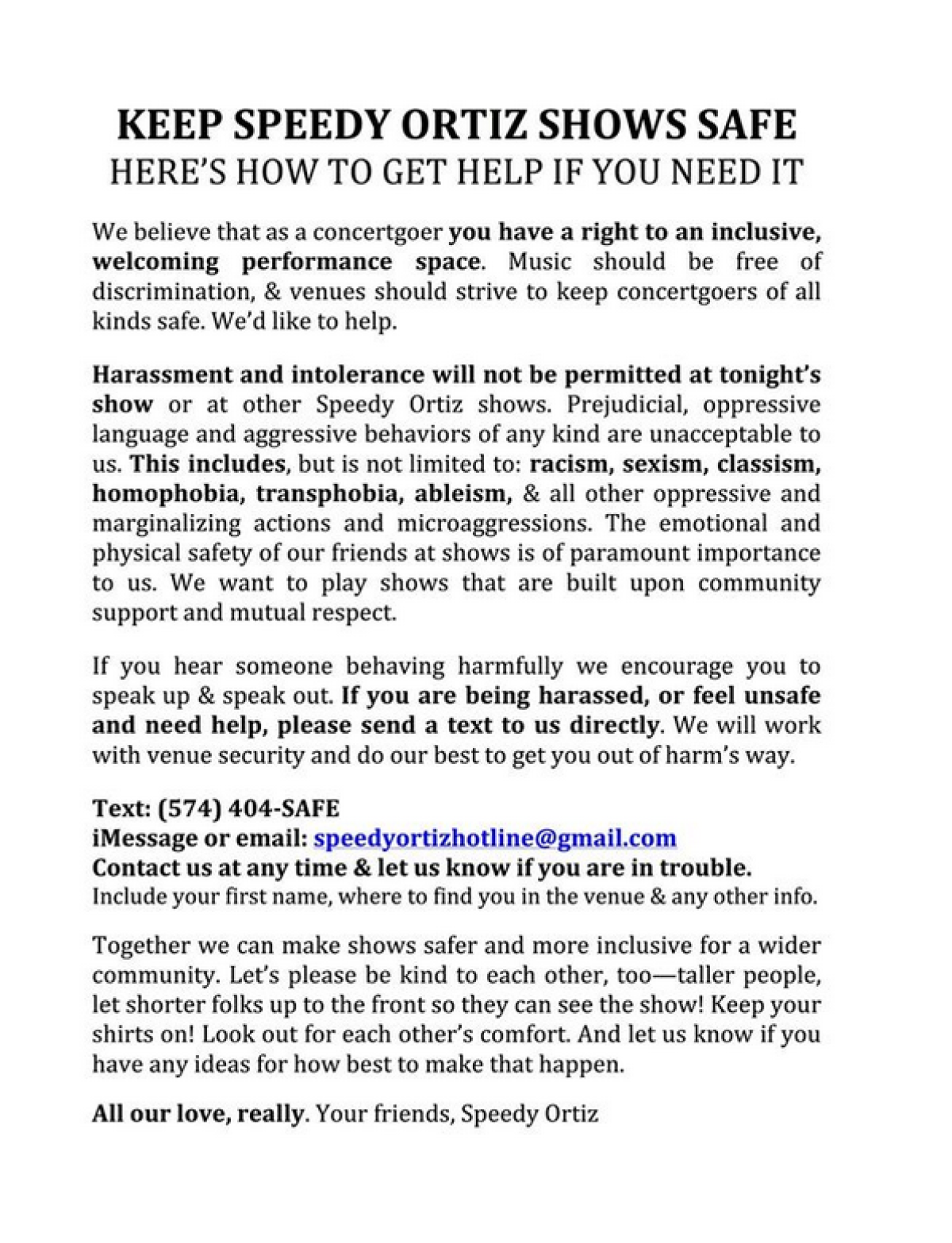

On Monday night, indie-rock band Speedy Ortiz offered a new service at a show in Ithaca, New York—a service it will continue to offer throughout the remainder of its fall tour to support its latest album, April's Foil Deer. The band announced yesterday on its Facebook page that it would provide a "help hotline" for fans who feel they have been harassed, disrespected or in any way victimized at Speedy Ortiz shows. Here's the full description:

The need for such a hotline may come as a surprise to some—namely, white males—but to others, some sort of measure to combat the various forms of harassment that transpire routinely at indie-rock shows is long overdue. For Speedy Ortiz frontwoman Sadie Dupuis, the decision to institute an outlet for victims came after an unfortunate experience at a festival this summer.

"We played a big festival and I went out and about for maybe an hour and a half, and there were maybe three different instances where I had to tell someone to stop disrespecting me," Dupuis tells Newsweek. "I was like, 'If this happened to me in the hour and a half I've been outside, I can't imagine all the people that have been dealing with this all day long and have nowhere to go.'"

There's a commonly held and largely tacit assumption that at concerts, where hundreds and often thousands of people huddle together in a confined space in the name of rock, one is permitted to shed every inhibition and indulge in every urge. Anything goes! Free expression! Free love! Look at the Sixties, man! It's what rock 'n' roll is all about! Sadly, over time, some fans have interpreted these aphorisms to mean that casually, or "incidentally," groping someone in the middle of a venue—only one of many forms of harassment the hotline aims to mitigate—is permitted.

For many, the rules of what constitutes acceptable behavior are loosened as soon as the first chord is struck at a show, and because so many people are present—literally, a mob—there aren't likely to be any consequences for passing acts of sexism or other forms of discrimination, both physical and verbal. As a veteran of the industry, Dupuis knows how to respond when she is victimized, but for most, silence is the easiest option.

"I'm lucky that I'm good at calling people out or finding someone to take care of it, but not everybody feels so bold," Dupuis says. "There are people who might be stuck in a dangerous situation and fear that going to security might further enrage the person that's causing the problem."

"If this happens to someone else who has no idea who to contact, they'd just be left feeling violated," she adds.

The response to Speedy Ortiz's announcement has been overwhelmingly positive, but there are still some who have said they can't imagine this type of harassment occurring at the band's shows—a common misperception is that the type of music being played dictates whether or not harassment is taking place (it doesn't)—and even some who, as Dupuis said, worry the hotline would be "getting rid of the fun."

In addition to offering an outlet for victims, part of the purpose of the hotline is simply to make those who are surprised by or disagree with the need for the service aware of the prevalence of discrimination at indie-rock shows. Last month, music journalist Jessica Hopper had the same purpose when she asked her Twitter followers to post instances in which they have experienced harassment or discrimination in the music industry. Hopper's call is the latest example of a dialogue around the issue that has sprung up in recent years, but it's not nearly enough, and in reality little has changed. "I can say that that for the amount of time since I started going to shows, I experience the same amount of [harassment] today as I ever have," says Dupuis.

Awareness is the first step toward action, and Speedy Ortiz's hotline is maybe the first practical example of the latter the industry has seen. Hopefully it will lead to more of both.

If you are being harassed at a Speedy Ortiz show, or feel unsafe and need help, text us directly: (574) 404-SAFE. https://t.co/ETCihzN9FU

— speedy ortiz ÷ haunted painting (@sad13) September 7, 2015

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Ryan Bort is a staff writer covering culture for Newsweek. Previously, he was a freelance writer and editor, and his ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.