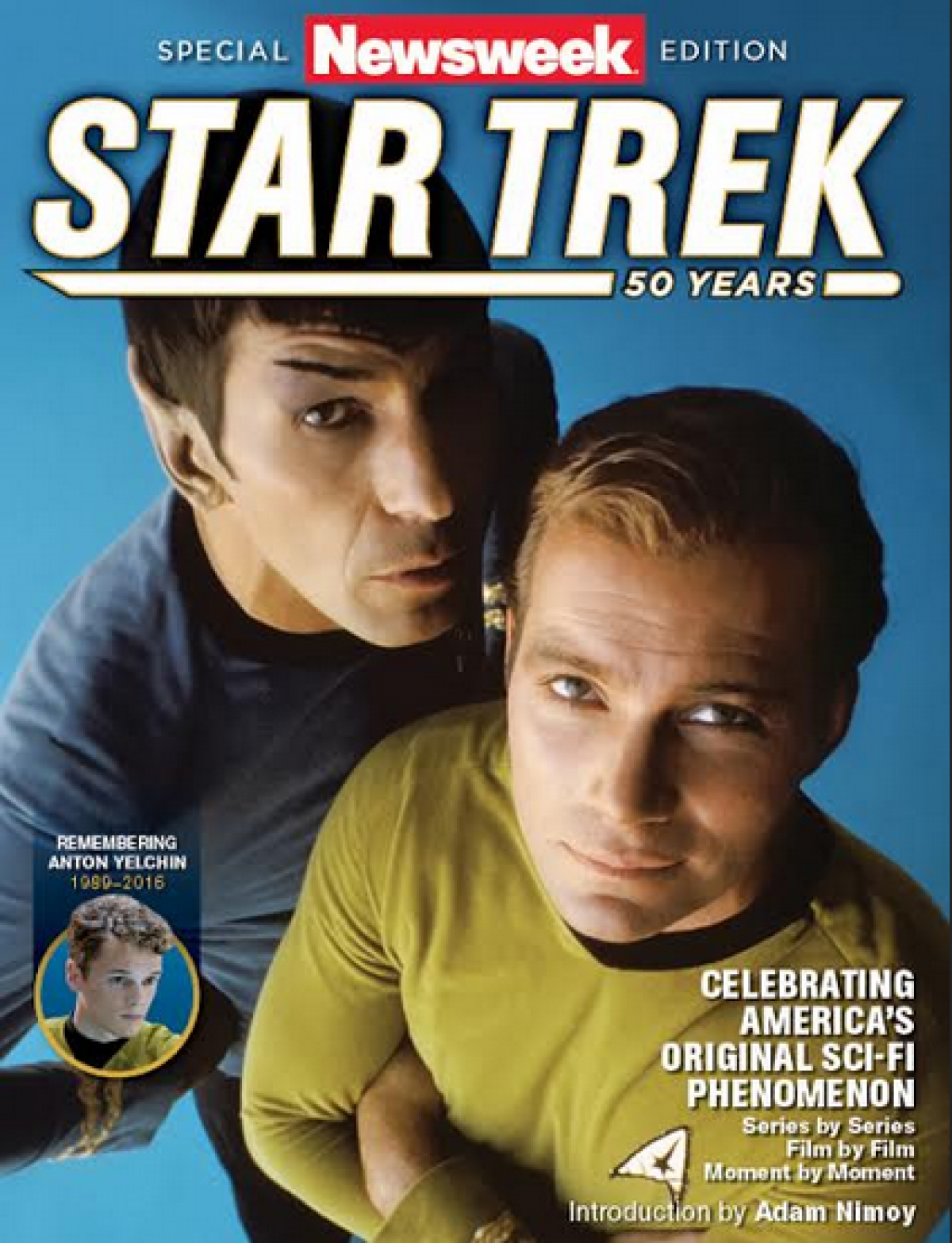

Star Trek began as a network failure, then became one of the most lauded scienc fiction fanchises of our time. This article, and others that honor the space saga, is featured in Newsweek's Special Issue Star Trek 50 Years: Celebrating America's Original Sci-Fi Phenomenon, by Issue Editor Tim Baker.

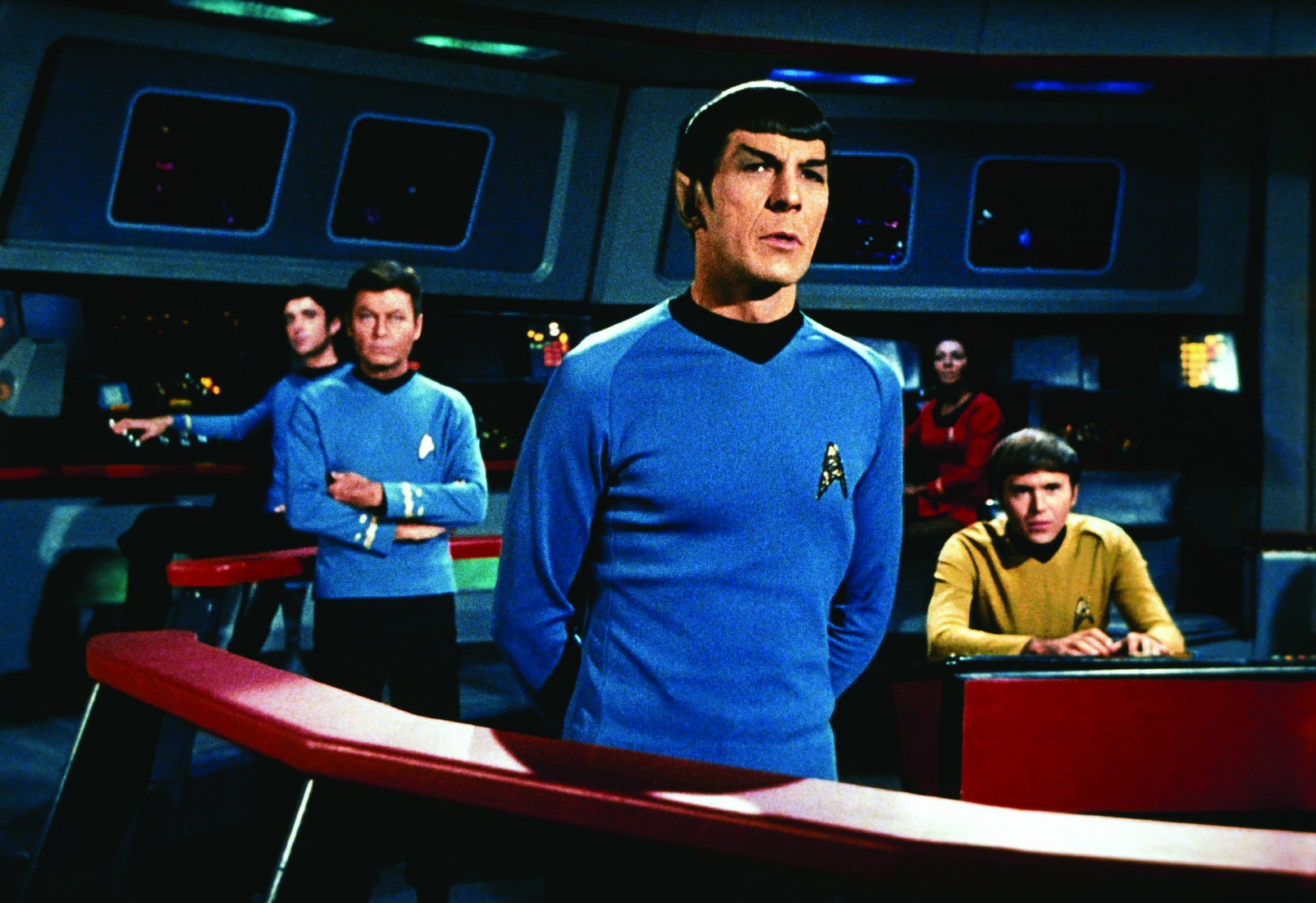

When CBS announced they would bring Star Trek back to TV in 2017, it came as a surprise to precious few observers. The adventures of Starfleet's finest have enthralled viewers with their hopeful predictions for the future and mankind's ability to endure since Captain Kirk and his crew appeared on-screen in 1966. When "The Man Trap"—the first aired episode starring William Shatner as James T. Kirk—premiered on September 8 of that year, it was the result of more than two years of constant work from Gene Roddenberry and his team. Space: the final frontier. The USS Enterprise, the flagship of the United Federation of Planets, glided into the silent and endless void on a five-year mission of exploration. It wasn't September 8, 1966, anymore; it was stardate 1513.1, and the greatest story in sci-fi history was just getting underway.

No one could have been aware of the unprecedented phenomenon the show and its many offshoots would create over the next half century, except perhaps Gene Roddenberry, who had fought nonstop for the previous two years to share his utopian vision of mankind's future with the masses. His original pilot, "The Cage," had been rejected by NBC, leaving Roddenberry with a choice: He could take to heart criticisms of the pilot's cerebral nature, the Broadcast Standards Office's complaints and the antiquated ideas about who could and should hold positions of power on the show—or he could stick to his guns.

Roddenberry stood firm, ignoring all doubters, and by the time America had seen Season 1, even the daughter of sci-fi legend Isaac Asimov (author of the Foundation trilogy and inventor of the three laws of robotics) was a fan. Asimov penned an essay for TV Guide entitled "Mr. Spock is Dreamy" and eventually became a close friend of Gene Roddenberry as well as an advisor to the show. More importantly, he made one of the first steps in a cultural shift that would eventually see Star Trek and its "low-culture" sci-fi ilkbecome some of the coolest properties in the pop lexicon.

Star Trek was part of the culmination of space fascination that had begun with Sputnik's launch in 1957 and wouldn't reach its peak until Neil Armstrong made his famous lunar steps in 1969. Put simply, "The Man Trap" was exactly the 40 minutes of TV a space-crazed American public wanted, whether they knew it or not. The episode, ratings of which belied the phenomenon Trek would become, set the tone for what would follow. Arriving at a distant planet, Kirk and the Enterprise crew encounter a mysterious creature that survives by extracting the salt from the bodies of its human victims. The catch? The creature appears to be the former flame of Leonard "Bones" McCoy, the ship's doctor. The emotional conflict created when McCoy faces the monster wearing his lover's face told viewers this was no ordinary space romp. There were pathos, drama and tragedy as well, and it would be these serious elements just as much as the flashy space decor and attractive aliens in elaborately small outfits that kept viewers addicted.

By late 1967, rumors began circulating that NBC would cancel Star Trek, but a letter-writing campaign saved the show for a while. Trek fans may have suspected they were on borrowed time from the start, but few could bring themselves to the realization that the fate of their favorite program seemed to be in the hands of people who didn't care nearly as much about the story of the USS Enterprise as they did. In the end The Original Series lasted for only 79 episodes, but love of and desire for more Trek continued to smolder.

A little more than a year and a half after Star Trek's cancellation and Armstrong's fateful steps, the first Star Trek convention was held in New York City, offering a tangible representation of just how many fans of this obscure sci-fi property continued to evangelize the show's merits to create new legions of Trekkers. By 1973, Trek was making its first triumphant return to the screen for Star Trek: The Animated Series, which brought back the lion's share of the original cast to reprise their roles as the Enterprise crew. The show was even more short-lived than its predecessor, but the world was far from done with Kirk and company, and Trek still had plenty to prove.

In 1977, Paramount Studios made the long-awaited announcement that a new live-action series, Star Trek, Phase II, was in the works, but after a May motion picture release called Star Wars became a phenomenon, Paramount re-thought the TV show and announced they would bring Trek to the big screen instead. Premiering in 1979, Star Trek: The Motion Picture offered a story rooted in the real world, with Kirk and his crew meeting the spacecraft Voyager, launched by NASA during the Carter administration, on its return trip to Earth centuries later. The antidote to Star Wars and its grounding in abject fantasy, The Motion Picture nonetheless received lukewarm reviews, and it took a great deal of negotiation to get one of the film's primary stars, Leonard Nimoy, to return for the sequel in 1982.

The Wrath of Khan, Trek's second big screen foray, is widely considered to be its best. The film brought back one of The Original Series' most memorable bad guys, Khan Noonien Singh, a remnant of humanity's darkest period. The incredible reception Wrath of Khan received created a school of thought among Trekkers that would gain strength until J.J. Abrams released his re-boot, the ninth installment of the Star Trek film legacy: Odd numbers don't bode as well as evens for the quality of Trek films. By the time Spock was killed in II, resurrected in III and given a bandana to hide his Vulcan ears from 1980s San Francisco in IV, it was clear to everyone involved in Trek, from Gene Roddenberry himself to the skittish executives at Paramount, that the world was ready for more Trek than it had ever seen.

When The Next Generation came onto the scene, it was originally thought of as a disappointment to some Trekkers who wanted to see the aging Kirk, Spock, Bones, Uhura, Scotty, Sulu and Chekov take the bridge again. But by 1990, Newsweek was reporting that "Fans love the new Star Trek more than the original," the magazine's story "Still Klingon to a Dream" read on October 22, 1990. "For Star Trek fundamentalists, the whole idea was beyond blasphemy. It was, well, illogical. A starship Enterprise without Spock and Bones dissing each other? A bald guy with a British accent sitting in the captain's chair? A Klingon serving as a senior officer? Was this any way to run Starfleet? Few Trekkies thought so. But in the three years since Paramount Television launched Star Trek: The Next Generation, a syndicated version of the venerable original, the protests have vaporized."

So successful was The Next Generation, in fact, that yet another series was launched while TNG was still finishing its run. For Deep Space Nine, the traditional format of a meandering spaceship finding adventures throughout the galaxy was abandoned in favor of the more politically minded action of a Federation space station. In an article called "Trek Sets a Bold New Course," which ran in our January 4, 1993, issue, Newsweek praised the new series as a breakthrough for several reasons. "Strip away its 24th-century trappings and Deep Space Nine is a politically correct Western," Newsweek staffers wrote. "It will also plunge viewers into an unprecedented time warp. When Paramount launches the series on January 3 (later in some areas), three different versions of the same sci-fi concept will be riding the airwaves simultaneously. None of them, however, tries harder to be different than Deep Space Nine."

By this point, Trek was on a roll, with film properties featuring the cast of TNG continuing the even-odd pattern of box-office receipts and reviews and yet another series, Voyager, set to air while Deep Space Nine was still in its original run. It may have seemed a risky move at the time, something that had the potential to saturate the market with too much Trek, but the adventures of Captain Janeway's epic quest across the galaxy was a Star Trek first in a number of ways. Janeway was the first female captain to anchor a series, USS Voyager was smaller in size than both the Enterprise and Enterprise-D—giving the series a more focused scope than its predecessors—and the series was the first original programming to appear on the UPN network. But beneath the differences, Voyager was made of the same hearty sci-fi stuff as the first three Star Trek series. This different-yet-the-same quality was meant to offer fans of Deep Space Nine, which ran alongside Voyager for the latter show's first five seasons, another way to explore the universe Gene Roddenberry created, this time bringing the action to the remote Delta Quadrant.

The sleek and relatively small USS Voyager was built, much like the series itself, to bring Starfleet back to its original principles of exploration of the unknown, and the series fittingly begins aboard Deep Space 9, where Janeway starts her mission aboard Voyager. After the highly successful Voyager run, Trek went into a brief hiatus from TV before riding a trend toward origin stories to the production of Star Trek: Enterprise. The series told the story of Captain Jonathan Archer and his intrepid crew of United Earth crewmen and women starting Earth's galactic exploration program. From the opening song, the first of any Trek series to feature lyrics, Enterprise was an underperformer compared to its predecessors, but by the end of the 2000s, an unlikely savior would start a new Trek renaissance.

Known primarily for his work on TV shows such as Alias and Lost, J.J. Abrams was exactly the man to reboot the Star Trek franchise and end any silly talk of an even-odd curse. Offering new takes on old characters while keeping the original Star Trek universe intact through a sneaky bit of time travel writing, 2009's Star Trek was the best of both worlds as far as most Trekkers were concerned. It allowed for a fresh take on familiar ideas, new interpretations of beloved characters, and even kept the unofficial Trekker #1, Leonard Nimoy, in his original role (now known as Spock Prime due to the timeline shift that allows both The Original Series and the Abrams films to co-exist) as a bonus. With the third installment of Abrams's series due out later this year and an all-new Trek premiering in 2017 on the small screen, another boom-time for Trekkers is upon us. No longer relegated to smoky hotel ballrooms and dingy comic book stores, Star Trek is now seen as what it always was to those in the know: something for everyone.

This article was excerpted from Newsweek's Special Edition—Star Trek 50 Years: Celebrating America's Original Sci-Fi Phenomenon, by Issue Editor Tim Baker. For more about the history of the federation and the upcoming movie, Star Trek Beyond, pick up a copy today.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.