"I don't believe in welfare," Nebraska governor Jim Pillen said in December 2023 in response to questions regarding the Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer.

His state was one of 15 that had declined to take part in the federally funded scheme, which will give families struggling with poverty additional money over the summer to help them feed their children.

In the run-up to the January 1 deadline for states to confirm participation in the program, Nebraskans took the fight to feed hungry kids direct to Pillen's door. Protesters held signs outside of the Governor's Residence in Lincoln, reading, "Why allow children to go hungry?" and "Food is the most important school supply."

Less than two months later, after pressure piled on by advocacy groups and ordinary Nebraskans, Pillen, a Republican, announced the state would backtrack on the decision.

Having spoken with children from low-income families, he said: "They talked about being hungry. And they talked about the summer USDA program and, depending upon access, when they'd get a sack of food. And from my seat, what I saw there, we have to do better in Nebraska."

Newsweek reached out to Pillen's team for comment via email.

Food banks in Nebraska have said the reversal means there will be less pressure on poverty aid services when schools are out for the summer.

"We continue to see record numbers of families coming to us to access food and this need always increases during the summer months when kids are out of school," Mike Hornacek, president and CEO of Together Omaha in Nebraska, told Newsweek.

But despite Nebraska's backtrack, there are still 13 states that have declined to join the program.

What Is the Summer EBT?

The program will provide additional funding to help feed children from low or no-income families. Those eligible will receive an additional $40 per month, a total of $120 per child, to pay for groceries when school is out for the summer this year.

The program, which was approved by Congress with bipartisan support, is expected to cost the federal government $2.5 billion.

It is a full-scale implementation of plans introduced in the coronavirus era. "The experience of the pandemic showed us that when government invests in meaningful support for families, we can make a positive impact on food security, even during challenging economic times," said Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack.

The Summer EBT comes at a time when food insecurity among families with children is rising.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 12.8 percent of all U.S. households were food insecure in 2022, amounting to 17 million households altogether. Food insecurity is defined by the USDA as when a household has difficulty providing enough food for family members due to a lack of resources.

Of households who suffered from food insecurity in 2022, the USDA found that 3.3 million of them have children—up by one million in 2021.

Feeding America, one of the country's leading charities combating hunger and poverty, said the Summer EBT will help feed around 20 million children in participating states.

"This new program could not be starting at a better time. In 2022, more than 13 million children in the U.S.—one in five—were living in food-insecure households," Vince Hall, Feeding America's chief government relations officer, told Newsweek. "This is a 44 percent increase from the prior year and the highest rate of child food insecurity since 2014."

Of the 37 states that have opted to participate, including Nebraska, 23 are led by Democratic governors and 14 are led by GOP governors. All states that declined the opportunity are led by Republicans. Those states are: Alabama, Alaska, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas and Wyoming.

On the January 1 deadline for the program, Louisiana was run by Governor John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, who stood down from his post over the new year. The Louisiana governor is now Republican Jeff Landry.

After initially declining to participate due to administrative costs, Vermont has tentatively joined the program after requesting a waiver from the USDA that would allow the state to administer the federal benefit without having to adhere to rules around data collection.

"It's sad," Vilsack said of states who opted out. "There isn't really a political reason for not doing this. This is unfortunate. I think governors may not have taken the time or made the effort to understand what this program is and what it isn't."

Why Have Some States Opted Out?

The opted-out states have given a variety of different reasons for declining the program, including costs—even with the federal government paying the entirety of the benefit and half the administrative costs. Other governors have said they don't want to continue with pandemic-era aid, while some have expressed they don't have faith in the federal government to administer the program. Still, the states that will not participate have faced criticism.

Some, like Iowa, already have their own state-run benefits programs for those struggling with the means to feed their children. But poverty experts and advocacy groups have laid the blame on political beliefs.

"South Carolina is one of 15 states proudly rejecting new federal funding from the USDA that would help feed hungry children over the summer," Dr. Annie Andrews, CEO of Their Future, Our Vote, told Newsweek prior to the U-turns.

She said the choice for South Carolina and other Republican states to decline the program is "politics at its very worst" and is being used to score "partisan political points."

South Carolina, according to the USDA data from 2021, has an overall child poverty rate of 19.7 percent. In some counties, this rate goes as high as 39.5 percent, over a third of all children.

South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster said in a press conference in January: "That [Summer EBT] was a COVID-related benefit. We've got to get back to doing normal business. We just can't continue that forever, but we're still continuing all the other programs that we have."

Newsweek reached out to McMaster via email for comment.

"This is not the time to make an argument about the need for smaller government, especially considering that South Carolina has no problem growing the government if it means they can tell a woman what to do with her body or tell the parents of a transgender kid that lawmakers know better than they do what is best for their kid. Kids are being harmed by these cynical political games," Andrews said.

In Iowa, Republican Governor Kim Reynolds blamed the government. "If the Biden administration and Congress want to make a real commitment to family well-being, they should invest in already existing programs and infrastructure at the state level and give us the flexibility to tailor them to our state's needs," she said in a statement released in December.

Newsweek reached out to Reynolds via phone call for comment.

In the same release, the Iowa Department of Health and Human Services said that Iowans can use food banks and charities if they are struggling for food. Iowa had a child poverty rate of 12.4 percent in 2021, according to the USDA's data.

Oklahoma, which is in the top 10 for highest child poverty rates in the U.S. with a rate of 20.5 percent, also declined the program. However, tribal nations within the state opted in. According to the Food Research & Action Center, approximately 403,000 would stand to benefit from the Summer EBT if it were implemented across the whole state.

Republican Governor Kevin Stitt said the state will not join due to a lack of clarity over rules that have not yet been finalized. "I think you need to ask the feds why they are wanting everyone to opt in before they even finalized the program," Stitt told reporters in January. He also said he is "satisfied" with current programs in the state.

Newsweek reached out to Stitt for comment via the contact form on his website.

Some Republican states that opted in for summer 2024 will not continue with it next year. Tennessee has said it will only participate for one year. Missouri has opted in for now—but not without sending a non-binding letter of intent. Officials said a lack of final guidance from the USDA "poses potential unforeseen challenges to the implementation of this new program for the 2024 summer."

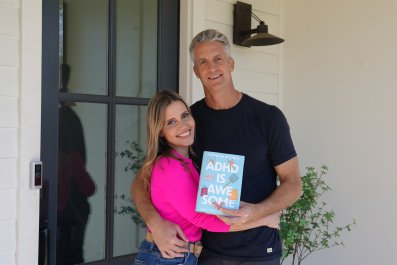

Not all Republicans hold the same line, however. Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders said the Summer EBT is "an important new tool to give Arkansas children the food and nutrition they need." Arkansas is confirmed to be taking part in the program this year.

In Nebraska, while the reversal by Pillen is welcome, the state still faces considerable challenges to ensure children are adequately fed in the coming months. "The food bank continues to face the largest hunger crisis in our history," Stephanie Sullivan from Food Bank for the Heartland told Newsweek.

While she admits that Nebraska's backtrack will have a "positive effect" on the families that use the service, the state's neediest will still be facing a troubling summer. "One in eight children in our state faces hunger and that number is unacceptable. We know that for many Heartland families, summer means one thing—hunger."

Are you in a state that has declined Summer EBT and have children who qualify for the assistance? Get in touch with a.higham@newsweek.com to share your opinion.

Update 4/8/2024, 9:17 a.m. ET: This article was updated to include comment from Stephanie Sullivan and to reflect Vermont joining Summer EBT.