Embryonic-stem-cell research has provoked more controversy—political, religious, and ethical—than almost any other area of scientific inquiry. This week the field suffered a legal blow with U.S. District Judge Royce Lamberth's ruling, which blocks the Obama administration's 2009 regulations expanding embryonic-stem-cell research.

Today, National Institutes of Health director Francis Collins weighed in, saying he was shocked that the court had issued an injunction against the research. "I was stunned, as was virtually everyone here at NIH," Collins told reporters during a telephone conference call. The ruling, Collins said, has the potential to do "serious damage to one of the most promising areas of biomedical research."

Numerous NIH grants and millions of federal dollars will be immediately affected. Fifty new human embryonic-stem-cell grant applications waiting for peer review have been put on hold, Collins said. About a dozen other grants involving human embryonic-stem-cell research that are further along in the approval process and total about $15 million to $20 million cannot move forward. And a freeze must be put on the renewal of 22 additional grants that had already been approved, equaling $54 million. The consequences, Collins said, are "dramatic and far-reaching." The Department of Justice, the Department of Health and Human Services, and others are taking this very seriously, Collins said, and are "working very hard" to figure out what steps will be taken next.

As yet another new chapter begins, we look back at the evolution of the field.

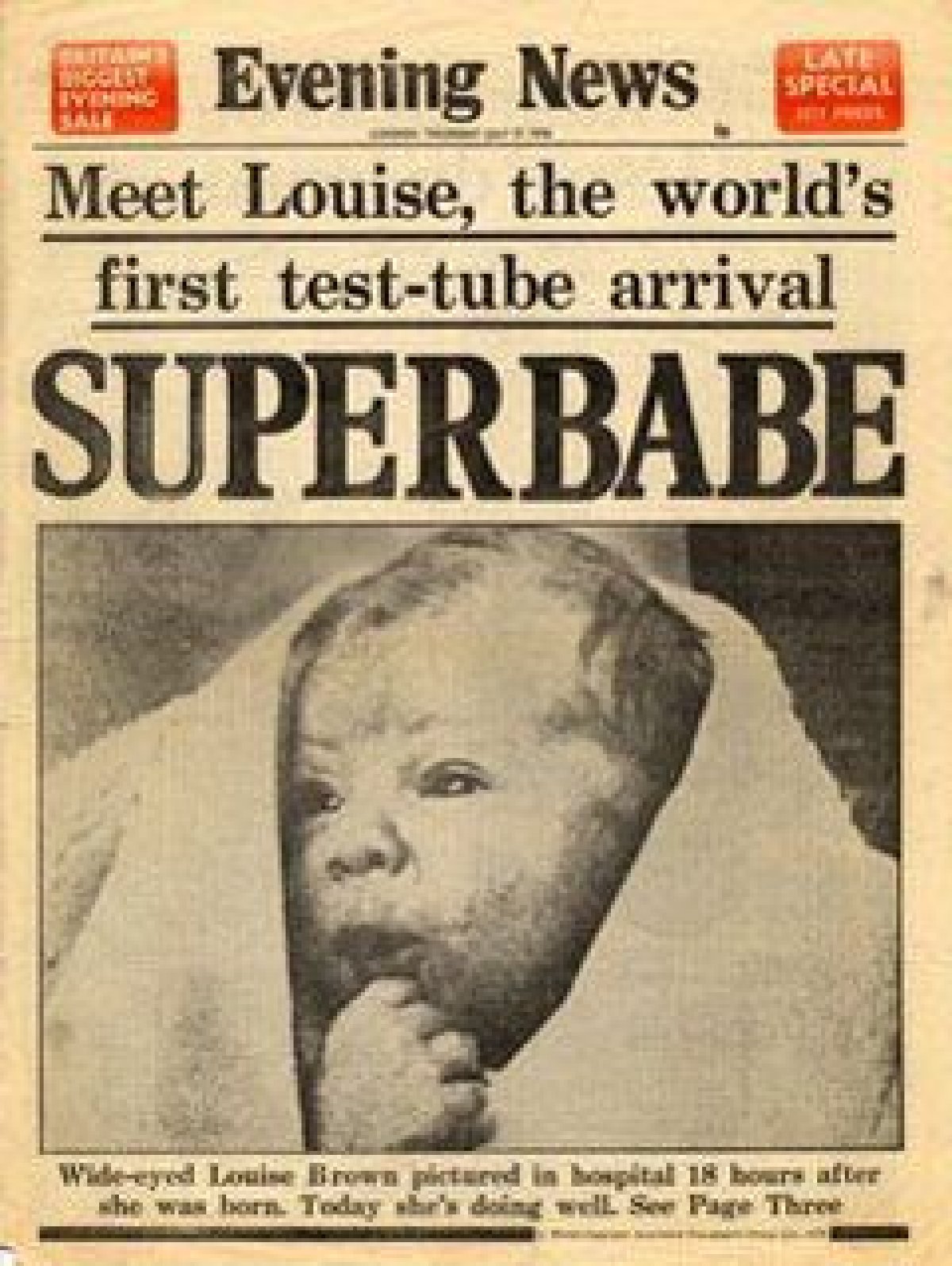

Louise Brown, a.k.a. the "test-tube baby," is born in England. Brown, pictured on a newspaper cover soon after her birth, is the first baby in the world to be conceived by in-vitro fertilization (IVF), a procedure that combines egg and sperm outside the mother's womb. Today, assisted reproductive technology is responsible for an estimated 250,000 babies born every year, but there is much debate about the fate of unused embryos, which play a vital role in stem-cell research.

Zoe Leyland, seen here as an infant, is the first baby born from a frozen IVF embryo, enters the world in Australia. An estimated 400,000-plus frozen embryos are now stored in fertility clinics across the U.S. Some will become babies one day; others will be discarded or remain frozen for years on end.

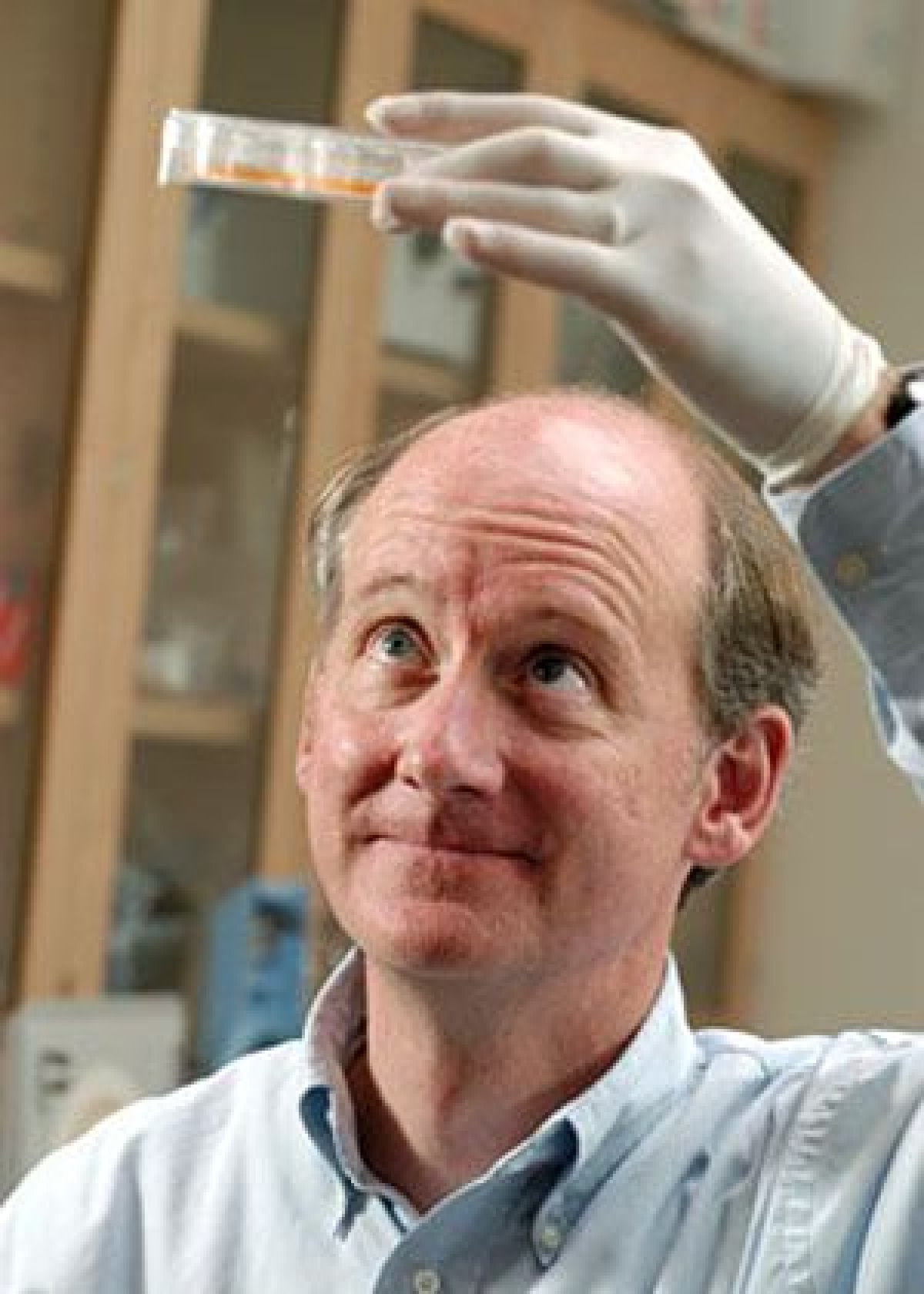

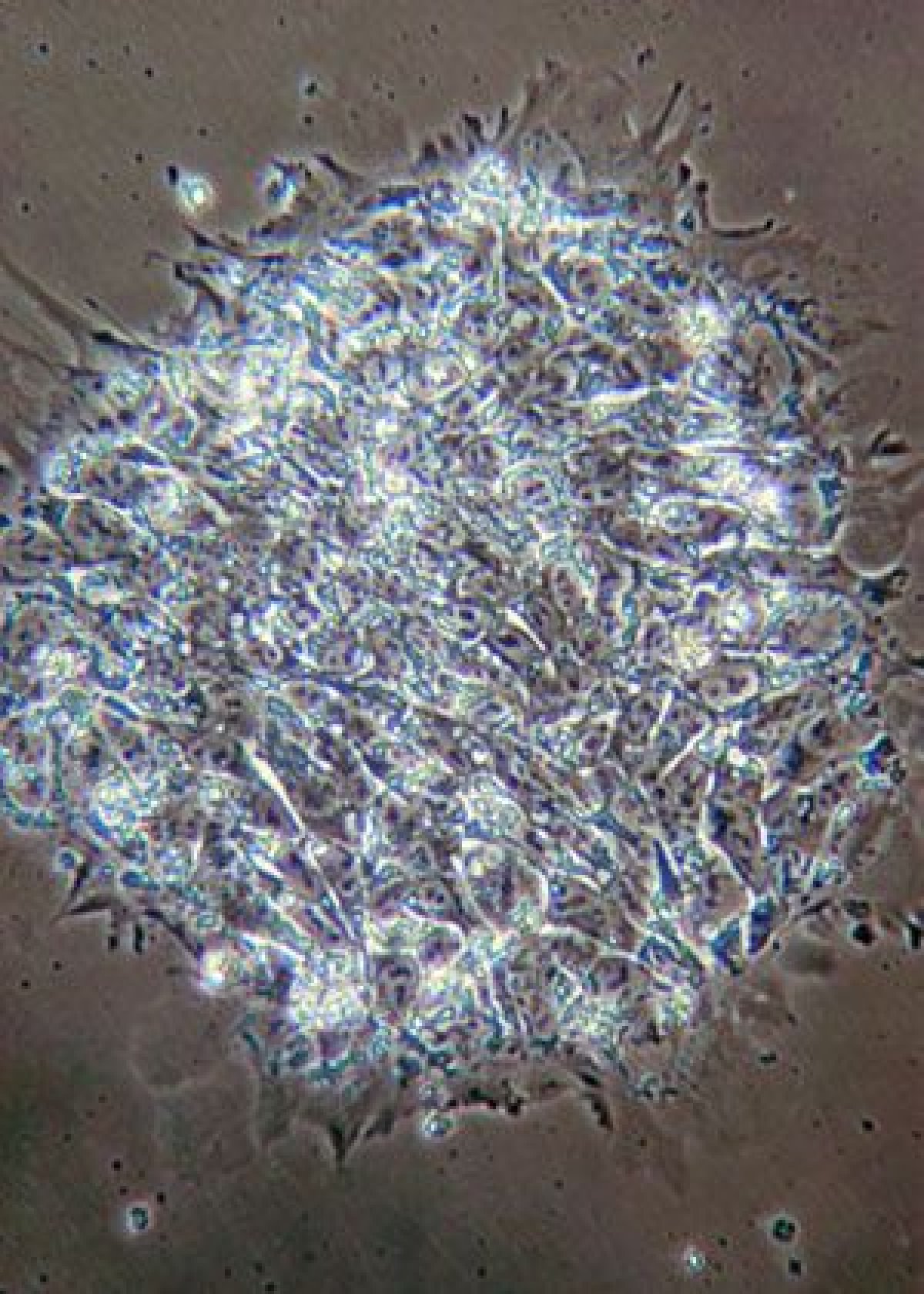

The first human embryonic-stem-cell line is isolated by Dr. James Thomson (shown here in 2003), a developmental biologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and colleagues. The team derived the cells from embryos donated by individuals who were undergoing treatment at fertility clinics.

President Bush limits federal funding of embryonic-stem-cell research to cells that were derived prior to his announcement, pictured here. Scientists, patients' advocates, religious leaders, politicians, and the public begin taking sides in the great embryonic-stem-cell debate. At one end: those who find the research morally unacceptable and oppose it altogether. At the other: those scientists and supporters who say Bush's criteria will handcuff research and stall medical advances.

The premiere journal Science publishes an eye-popping paper by Korean researcher Hwang Woo Suk. Hwang and his team report that they have created a single human embryonic-stem-cell line through cloning. A second report published one year later claims the creation of 11 additional "patient-specific" lines, carrying the genetic signature of patients with diabetes, spinal cord injury, or a genetic blood disorder. The notion that human embryonic-stem-cell lines can be derived from eggs alone—and not human embryos—creates a major buzz. But a report released by a Seoul National University panel two years later finds that Hwang fabricated evidence for his research. In this photo, Hwang is seen arriving for a 2006 court hearing in Seoul. In October 2009 he is convicted of falsifying his papers and embezzling government funds, and is sentenced to a suspended two-year prison term. The scandal rocks the stem-cell-research world.

Embryonic-stem-cell research polarizes voters in the 2004 presidential election. On Election Day, Californians vote to allocate $3 billion in state funds over 10 years to stem-cell research. Here, Robert Klein, chairman of the "Yes on Prop 71" campaign, is shown celebrating with allies. Other states—including Maryland, New Jersey, and Massachusetts—and private institutions begin investing in embryonic-stem-cell research as well, sidestepping federal restrictions.

President Bush vetoes a bill that would allow federal funding for stem-cell research on embryos discarded by IVF patients. In a press conference, shown here, he is joined by children produced by "adopted" embryos, often referred to as "snowflake" families. "These boys and girls are not spare parts," he says. Most couples, however, do not want to donate their embryos to other couples.

Two teams of scientists report that they have created "induced pluripotent" stem cells (iPS cells), which have similar properties to embryonic stem cells, without human embryos. One team, led by Kyoto University researcher Shinya Yamanaka, uses adult human skin cells to derive the iPS cells; the other, led by the University of Wisconsin-Madison's Dr. James Thomson, uses newborn foreskin cells. (Pictured here is Junying Yu, an associate scientist on Thomson's team who was the lead author of the study.) Both sides of the embryonic-stem-cell debate hail the advance but disagree on what it means. Opponents say researchers no longer need to conduct research on human embryos; scientists say embryonic stem cells remain the gold standard and the science must proceed on all fronts.

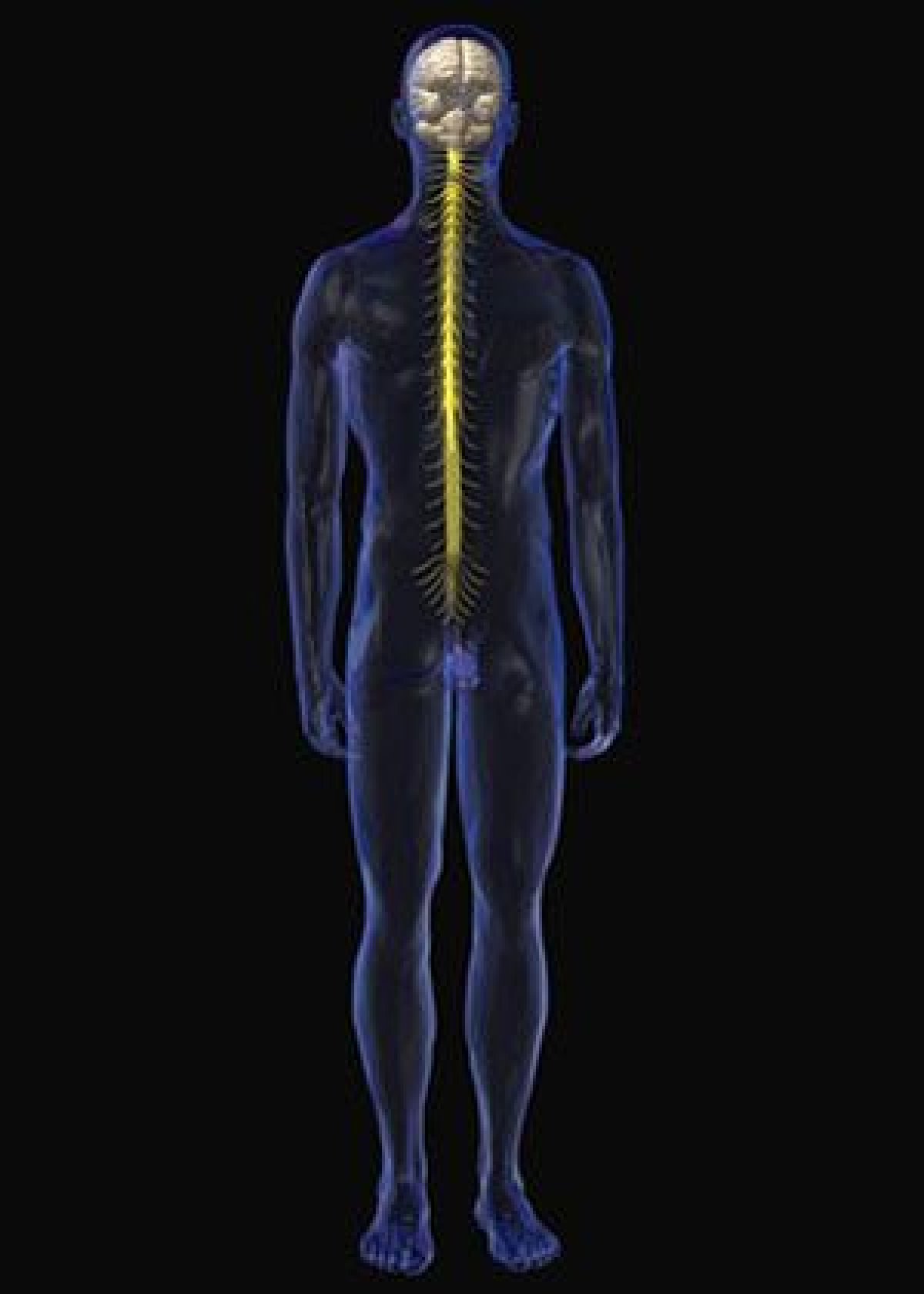

California biotech company Geron announces that it has received FDA clearance to launch the world's first human embryonic-stem-cell clinical trial. Geron, which plans to test an embryonic-stem-cell-based therapy in patients with acute spinal-cord injuries, hoped to begin recruiting patients in 2009, but the trial was initially put on hold by the FDA following preclinical results in animals that showed a higher frequency of cysts. In July 2010, Geron announced that the FDA hold had been lifted and the clinical trial would proceed.

President Obama signs an executive order lifting Bush-era limitations on human embryonic-stem-cell research (pictured here). The National Institutes of Health (NIH) crafts new draft guidelines for scientists, then receives 49,015 comments in response. NIH publishes its final guidelines in July.

The NIH approves 13 human embryonic-stem-cell lines for federally funded research. NIH director Dr. Francis Collins, an evangelical Christian, tells reporters in a conference call that even people who believe in the inherent sanctity of the human embryo can ethically support research on embryos that would otherwise be discarded. "Many people who've looked at this have come to that conclusion, including me," he says. Two weeks later, 27 additional lines are approved. The total for 2009: 40.

Chief Judge Royce Lamberth issues an injunction blocking the Obama administration's 2009 regulations expanding embryonic-stem-cell (ESC) research. Lamberth's ruling comes down in favor of two scientists who work exclusively with adult stem cells and are opposed to the research. The main point of contention is a law known as the Dickey-Wicker amendment, which prohibits research in which a human embryo is destroyed or discarded. The NIH allowed federally funded research to be conducted on embryonic-stem-cell lines that had already been created. But Lamberth writes that the government's guidelines violate Dickey-Wicker's prohibition "by allowing federal funding of ESC research because ESC research depends up on [sic] the destruction of a human embryo."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.