Pennsylvania state legislator Jewell Williams had just picked up his dry cleaning and was driving home through North Philadelphia when he noticed that three police officers had stopped a car with two elderly black men inside. The officers frisked the driver, and when a cop set his cash down on the trunk of the car, the loose paper bills fluttered away in the wind and were scooped up by patrons from the nearby Red Top bar. "So I got out of the car, and I was yelling to the people, 'Yo, leave that man's money alone!'" says Williams, who is black, looking out over hardscrabble York Street as he describes how he got sucked into a landmark stop-and-frisk lawsuit that would change the city and mirror similar fights all over the country.

The cops got angry. They swore at and handcuffed the driver and passenger, a city employee and a retired tailor, and put them both in a patrol car. Williams, standing next to his black Chrysler with legislative tags, pulled out his state representative ID and even pointed to his home, which was on the other side of an overgrown lot. "Get back in your fucking car before I give you a bunch of tickets," one cop told him, according to court papers.

When Williams, a retired Temple University police officer who is now Philadelphia's sheriff, told the cops he wanted to speak to a supervisor on that March 28, 2009, day, one officer ratcheted cuffs tightly around his wrists, and a sergeant who had arrived on the scene pushed him inside a police car. The cops ferried the two handcuffed elderly men a half-dozen blocks in the back of a patrol car as another cop drove their car to the same spot. The men were dropped on the side of the road without charges, with the police returning their car and cash—minus the bills that blew away, court papers state. Williams was held for much longer as his constituents looked on and his daughter pleaded with the police to let him go. "I sat out here like I was on public auction," he tells Newsweek, echoing the experiences of countless black men who have sat on curbs in front of their families. "Then we went to the district."

Williams, a tall man, rode to the 23rd District police station handcuffed and in the back of a patrol car with his size 13 feet propped up on the seat beside him. He was released several hours later without charges. Later that evening, he met with then-Mayor Michael Nutter and his police commissioner. But Williams wasn't pacified. He sued the City of Brotherly Love in 2010, the ex-cop reluctantly becoming a lead plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit that accused the city of an illegal stop-and-frisk policy that targeted black and Latino men. The lawsuit and the ensuing 2011 settlement have slowly forced Philadelphia, home of the Liberty Bell and the nation's fourth-largest police department, to change how it stops and searches its residents. But a March 22 report written by the lawyers representing Williams found that police are violating the settlement, and the lawyers threatened to seek sanctions if no progress is made within six months.

That ugly scene outside the Red Top and the changes it sparked reflect a national push to reform stop-and-frisk, which can be either a valuable tool to catch criminals or an ugly wedge that makes minorities hate cops. "Philly is not unique. Philly is part of a larger picture around the country," says Ezekiel Edwards, director of the American Civil Liberties Union's (ACLU) Criminal Law Reform Project. "The police in city after city are targeting poor communities of color and using their discretionary and fairly awesome authority to stop somebody on the street walking to work, on the subway, on a bike, and questioning them and often frisking them to see if they come up with anything."

Police in New York City stopped almost 700,000 people in 2011, the peak year under then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg. But a class-action lawsuit almost identical to the one filed by Williams resulted in a federal order that police stop someone only if they have a reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing or is about to commit a crime. The number of stops last year fell to 23,000. That's a huge drop, but the litigation is ongoing: Earlier this year, the federal monitor said in his latest report that in over a quarter of the New York stops he reviewed, police weren't recording the suspicion that made them stop a suspect. The number of street stops in Chicago reportedly fell by 80 percent this year after a new policy made cops document their stops with a two-page "investigatory stop report." And last year, the Boston Police Department implemented a policy that bars stops based on race after a report found that cops were mostly stopping black people. In the past year, Newark, New Jersey, and Cleveland both signed agreements with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) that will revamp how their police stop and frisk.

To get a clearer picture of racial profiling, Minneapolis police last year started recording both the race of the people they stop and the reason. Ferguson, Missouri, settled a DOJ probe this year by promising reforms to its cops and courts, including stop-and-frisk, and Seattle has had a federal monitor overseeing how its police stop and search since early 2014.

Philadelphia has long had legal fights over the practice. In 1985, then-Police Commissioner Gregore Sambor ordered his officers to search for drugs on everyone who walked through 51 intersections frequented by dealers. He then invited reporters to watch "Operation Cold Turkey," and some police districts even made up rubber stamps to mark the arrest forms with the name of the operation. Over two days, the cops arrested 1,444 people, almost none of whom were doing anything wrong, including one diabetic man who was on his way to dialysis.

The ACLU filed a federal lawsuit less than a week later, and the city quickly settled it with payments of $100 for anyone stopped and $1,250 for anyone stopped and arrested—plus the promise never to stop and frisk people based on their presence in a designated area. In the late 1980s, two other federal cases rapped Philadelphia for illegal stops, and yet another federal lawsuit was settled in 1996, with a $6 million payout and a plan to monitor the practice.

"We used to be better known for police brutality than for cheesesteaks," says David Kairys, a law professor at Temple University and longtime Philadelphia civil rights attorney who brought the Operation Cold Turkey lawsuit. Kairys tells Newsweek he believed the settlement for that suit would eliminate "rampant profiling and stops-and-frisks without a basis…. But I quickly realized that it didn't and it won't."

Sitting at a conference table in his grand, wood-paneled office, Mayor Jim Kenney and his police commissioner, Richard Ross Jr., responded to Newsweek's questions about stop-and-frisk. As I ask my first question, Kenney interrupts: His police don't do stop-and-frisk—"constitutional pedestrian stops" is the term he prefers.

"There was stuff that the police did during the Rizzo years—the cops were in charge," Kenney says later in the interview, referring to Frank Rizzo, the police commissioner and then the mayor—from 1968 to 1980—who was often accused of police brutality both by himself and his officers. Kenney described the Rizzo years as a period when citizens had a choice between following police orders quickly or getting smacked. "You did what you were told, and if you didn't do it fast enough, you got your head split open. That's what we're dealing with now, the residual of that history...and it's hard to correct it in four months."

Kenney, who took office in January, says the numbers outlined in a recent report—a third of stops and almost half of all frisks were made without reasonable suspicion—reflect the previous administration and aren't "our numbers." (Philadelphia police stopped about 215,000 people in 2015, but the first quarter of 2016 showed a 10 percent drop in the number of stops compared with the same period last year, according to David Rudovsky, a lawyer representing Williams and the other plaintiffs.) Kenney also says reform is necessary to create an environment where citizens will give police information about violent criminals.

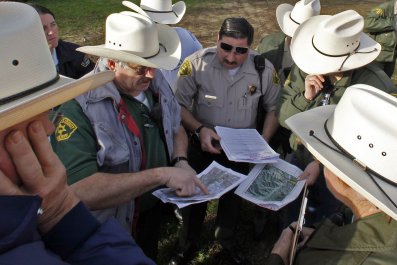

Ross, who was deputy police commissioner when Williams was arrested and attended the meeting in which then-Mayor Nutter apologized, lays out the reforms he and the mayor say will cut the number of unconstitutional stops. For the first time, police officers will face progressive discipline if they fail to fill out the reports that document their stops. The 21 captains who oversee the city's 21 police districts now examine those reports each day, instead of their bosses reviewing them once every three months.

On weekdays, the plaza outside City Hall fills with young professionals drinking iced coffee and eating $10 sandwiches. But walk north on Broad Street toward the neighborhood where Jewell Williams was handcuffed and the city changes in just a few blocks. I stroll by churches and gas stations, and the New Freedom Theatre, which has posters up for a play titled The Ballad of Trayvon Martin. There's a burst of businesses and activity clustered around Temple University, but when I reach York Street, three miles north of City Hall, there are empty lots and boarded-up buildings, and a man standing outside a gas station on one leg and two crutches asks me for a dollar.

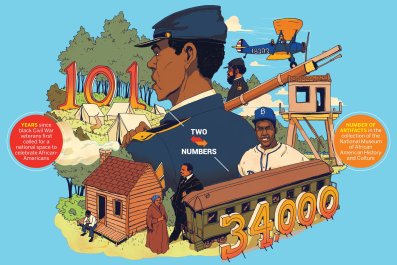

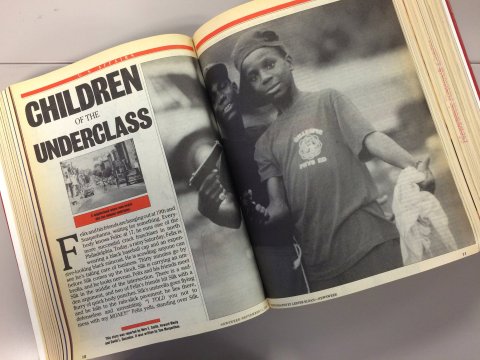

I think of a 1989 Newsweek feature story about the neighborhood that described the flourishing drug trade, showed children holding guns and called Williams an "ombudsman for a neighborhood in serious trouble." A beat cop even said the neighborhood was too crime-ridden to be saved, noting, "We lost this generation."

On the street where Williams was arrested, residents are split on the question of stop-and-frisk. Mildred Wagner, 24, an Amazon delivery driver, criticized the way the practice is carried out in terms that mirrored what Kenney told me earlier that day. "It's not the 1970s—they don't have the right to stop and frisk anybody," she says, sounding like statements in any one of the lawsuits that have been filed from coast to coast to reform the practice. Wagner described how police stopped her about 18 months ago as she returned from a Rite Aid store, then ordered her to get inside her house. "I wasn't doing any mischief. That makes me feel like I can't trust the police."

But some of the people who hate being stopped on York Street are police targets for a legitimate reason. "The last time I got stopped and frisked, I did four years," says Quadir Smith, 26, who admits that he was stopped and arrested on marijuana and gun charges.

Melvin Carter, a 51-year-old demolition worker, says, "They need to get these guns off the street. If that's the only way they can do it, I'm 50 percent for it."