Does the world need a vaccine for strep throat? In a rare alignment, the pharmaceutical industry and global health advocates like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation both see such a shot as a low priority. And for the many American families for whom strep is just a routine, if annoying, feature of winter, that perspective may seem correct. But two researchers on opposite sides of the globe disagree—and in light of a recent spike in deaths, rising antibiotic resistance and a litany of other issues caused by this seemingly manageable infection, they may just be right.

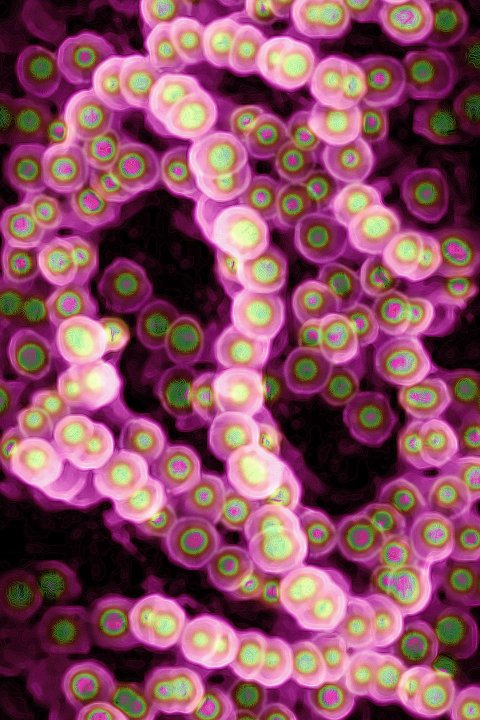

The group A streptococcus bacterium, the microbe responsible for strep, causes 616 million cases of sore throat each year worldwide. An untreated infection can lead to scarlet fever, flesh-eating infections and toxic shock syndrome. Streptococcus can also trigger rheumatic fever, a leading cause of heart disease around the world.

The financial cost is high too. One 2008 estimate, published in Pediatrics, placed the total dollars spent on sore throats due to strep infections between $224 million and $539 million per year in the United States.

A vaccine against group A streptococcus would prevent these complications. Just like the successful immunizations against the bacteria that cause measles, mumps and tetanus, a shot to prevent streptococcus infections could save lives and reduce health care costs. And although creating a strep vaccine is a trickier proposition than it was for those other pathogens, evidence is mounting that it isn't impossible.

Fragmented Efforts

Most immunizations work in the same way: using tiny pieces of the proteins found on an invader's surface. These pieces of proteins can act like a wanted poster for the immune system, telling it what to look for. The next time the immune system senses an invader that looks like these proteins, its cells can produce antibodies to contain it more quickly.

But strep is challenging. Different strains of the bacterium can cause disease, each with slightly different versions of a protein—called M protein—that the bacterium uses to infect people.

Dr. James Dale thinks he's figured out a solution to that problem. An infectious disease specialist at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Dale has been refining an extremely complex strep vaccine. To protect people against as many strains as possible, Dale's vaccine uses pieces of different M proteins. "In the early days, we didn't know how to do that because it seemed daunting," he says. Technological advances have made things easier—though not necessarily easy.

Three dozen volunteers at the Canadian Center for Vaccinology, located at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, recently received a version of Dale's vaccine. The study is based on previous evidence that an earlier version was safe and effective. It will take another few months for Dale and the CCV team to know if this new version is also safe, but the preliminary data look good.

Halfway around the world, Dr. Michael Good and his colleagues at Australia's Griffith University are developing two vaccines against strep bacteria: one to prevent skin infections and another to prevent throat infections. Good and his team are using just one fragment of an M protein—a fragment that looks the same among strep strains—to work against most of the strains seen around the world. They await results from a pilot study with 10 people.

Strong results don't ensure the vaccine will ever become available. Food and Drug Administration approval requires that a pharmaceutical company invest tens of millions of dollars, with no guarantee of a profit. Of the 238 vaccines for all diseases that began Phase I trials between 2005 and 2016, just 16 percent were eventually approved.

Only established companies and major international foundations can make the kind of investment required; none have done so for strep yet. "You would think that a lot of parents and most people would be interested in a vaccine to prevent strep throat," Dale says. "The pharmaceutical industry does not believe that's the case."

Just four major companies sell most vaccines: Merck, Sanofi-Pasteur, Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). The reasons for that limited interest are economic. Unlike blood pressure drugs, for example, vaccines—administered just a few times over a person's life—offer no steady revenue stream. They also tend to cost more to develop.

This doesn't mean there isn't a viable market for vaccines. An improved shingles immunization was approved earlier this year, and a new cholera vaccine was approved in 2016. It's just been a tough road for the strep vaccine. In 2005, GSK bought a company called ID Biomedical, which held the license for an earlier version of Dale's vaccine. GSK soon dropped the program, and eventually the license wound up with Dale's own company, Vaxent.

That decision, Dale says, may have been because the company didn't see a market in the United States. American parents might prefer doctor visits to a vaccine when it comes to treating their child's strep throat. After all, the serious complications that come with strep are exceedingly rare in the U.S., as are invasive strep infections like flesh-eating bacteria. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), only about 12,000 people suffer from invasive strep in the U.S., and most make a full recovery. Approximately 1,100 Americans die from the infections or related complications each year.

The real need lies outside America, where money is tighter. A group of researchers estimated that at least 319,400 people died from rheumatic fever–related heart problems in 2015, mostly in Asia. Over 100,000 people died in India alone, the most of any country. "The major need for a vaccine is actually in low- and middle-income countries where a significant burden of disease exists," Dale says. Some vaccines balance these needs; the hepatitis B shot costs more for people in higher-income countries than in lower-income ones, for example. But if parents in higher-income countries don't get the vaccine, the math may not look good to a pharmaceutical company.

It's possible that the industry is underestimating the American public's readiness for a strep vaccine. "We're moving into an era where vaccines are being developed for diseases that don't kill people but cause frequent infections or frequent disease, or are troublesome or annoying in one way or another," says Dr. Mark Sawyer, a pediatric specialist at the University of California, San Diego, and the Rady Children's Hospital San Diego.

Many parents follow the advice of their pediatricians, who in turn generally follow the advice of the CDC. The agency sets the recommended vaccination schedules for children and adults, and a strep vaccine would likely be added to this roster. "Were there to be a vaccine that would be safe and effective, it would be recommended universally for children here," says Dr. Paul Offit, an infectious disease expert at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia who served for years on the CDC committee.

Becoming Deadly

Whether the vaccines being developed by Good and Dale will prove safe and effective remains to be seen. If a vaccine doesn't provoke a strong enough immune response, it will be useless. And if the immune reaction to a vaccine is too strong, a person can die.

Death isn't the only problem. The antibodies involved in that immune response, if turned against the body that made them, can damage the heart—that's what causes rheumatic fever. History supports this concern: A 1970s strep vaccine project wound up giving two of the 21 test subjects rheumatic fever. Sixteen others developed strep infections. "This experience indicates the need for extreme caution in the use of streptococcal vaccines in human subjects," the researchers wrote in their publication of the failed study. The high risk, combined with a not necessarily high reward, may help explain why no company has jumped into the fray with some funding.

If pharmaceutical companies aren't interested, organizations dedicated to global health would seem like the next obvious option. The Gates Foundation, for example, has supported a variety of global health projects that develop vaccines for, among other diseases, malaria, dengue and meningitis. "It would make a huge difference to the field if Gates got behind it," Good said.

But a spokesperson for the Gates Foundation said it hasn't supported a group A strep vaccine because it falls outside the organization's central goal: reducing child mortality. The disease doesn't often kill children under 5 years old, and rheumatic fever usually strikes young adults.

Both the Gates Foundation and the pharmaceutical industry may now have a reason to re-examine their stance on a strep vaccine. Dangerous infections are re-emerging, even in parts of the world with a relative abundance of medical resources. In England, the number of cases of scarlet fever has tripled over two years, researchers reported in The Lancet. A 2016 outbreak of strep killed at least nine people around London, Ontario.

It's showing up in U.S. hospitals too. Offit recently saw a child with pneumonia as a result of strep infection, as well as knee infections and cases of toxic shock syndrome due to the strep bacteria. It nearly killed someone in New York City last summer.

In the world of vaccines, death is one thing the commercial powers can't ignore.