The opening scene of Sully, the new Tom Hanks/Clint Eastwood movie about the "Miracle on the Hudson," takes place in a midtown Marriott, in the mind of U.S. Airways Captain Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger, and the image is pretty much what every New Yorker expects when they see an airplane flying way too low over Manhattan.

The title character wakes from his fiery nightmare in a cold sweat, only to find himself in another dream—that of an average man transformed into a hero. Except that it's not a dream.

I went to see Sully expecting it to be the film version of patriotic doggerel. Instead, there were parts of it that moved me to tears. It's a terrific disaster movie that is not a disaster. It is packed with gorgeous aerial footage of New York City's architectural contour—soaring works of brick and steel framed against the January sky, so gorgeous and, as we now know, also so fragile. Even the desperate "water landing" itself looks more graceful than terrifying.

It's a love letter to the city and to the men and women who every day drive the commuter ferry boats and serve on the little NYPD boats and drive Coast Guard cutters around New York Harbor, and the courageous "scuba-cops," as Tom Hanks calls them, who don rubber gear and oxygen tanks and leap from helicopters into freezing, deadly waters. It celebrates these people do their jobs every day, not just on that strange, frigid afternoon of January, 15, 2009, when they came together and in a mere 24 minutes saved every one of the 155 souls on board the bird-stricken, sinking US Airways flight 1549.

Besides being a paean to New York, and life-saving New Yorkers—the ultimate 9/11 movie topic—Sully also is about what happened behind the scenes when federal bureaucrats at the National Transportation Safety Board start trying to figure out if Sully really needed to ditch his plane in the Hudson. First of all, they disagree on the nomenclature: The investigators want to call it a crash. Sully insists it be called "a water landing." But since millions of dollars of Airbus A320 hardware was lost, and something did indeed go very badly wrong in the air, the NTSB and the airline need to know if anyone is to blame besides the geese.

At this point, the movie treads into vaguely Republican political territory—not surprising since director "Make My Day" Eastwood is a well-known fellow traveler in Trump world. The conflict at the heart of the movie is man against faceless, machines of bureaucracy. The antagonist is the computer simulator that tells the investigators Sully could in fact have made it over to La Guardia or Teterboro Airport in Jersey, with two dead engines.

Man Against Bureaucracy

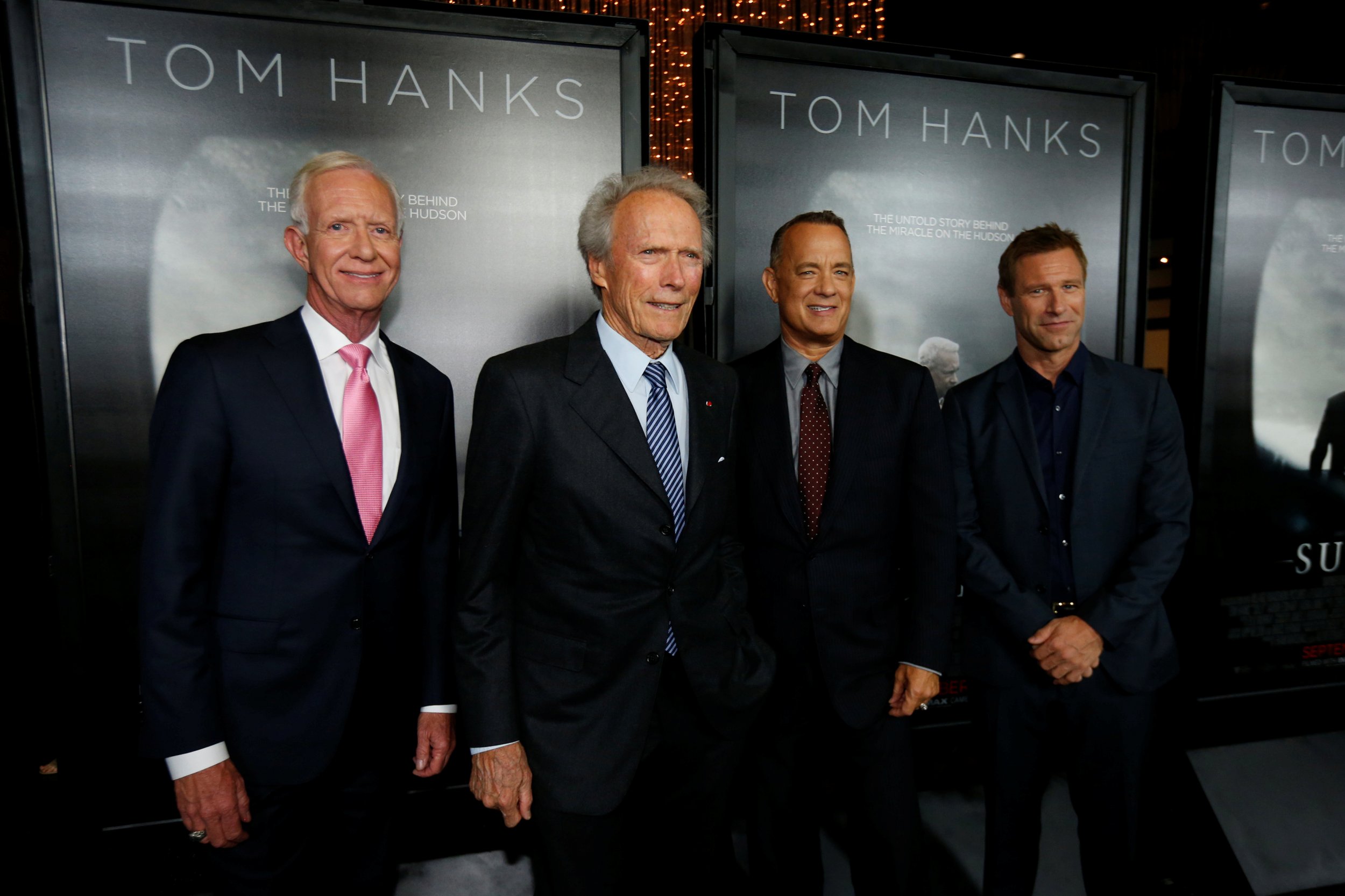

In an interview at a lunch for the movie on the Intrepid, Eastwood demurred on whether he thought his movie had any political relevance. "I don't know, I never thought of it," he said. But he agreed that federal bureaucrats were the antagonists. "It's always that way, isn't it?" he said. "A person trying to do right, and the bureaucracy is working against him. And he had to be creative to find a way to do the right thing."

On the surface, Sully is the "simple man"—that guy everyone including he can "love and understand," as the Allman Brothers once put it.

But becoming a hero—especially in a mythic city like Gotham, and especially in post 9-11 Gotham—is no simple thing. The film depicts him having to take to jogging in the frigid Manhattan night to shake off both the PTSD of the crash and interrogations with crash investigators. He stops in a Times Square bar and is recognized: the bartender proudly pours him a drink he named after the event: a shot of Grey Goose and a splash of water. Sully graciously accepts the gift, without letting on that to him, it's not funny, and Hanks perfectly conveys the combination of unease, horror, generosity and kindness in the still shell-shocked captain's face.

Eventually, the bureaucrats came around and joined the public in its assessment of "The Miracle on the Hudson."

Sully insisted that "the human element" in Sully's decision-making process—time—be added to the simulation. The computer flight simulators took off from the runway knowing that they would lose power in both engines in a matter of minutes, which enabled them to react instantly when the bird struck. Sully and his co-pilot Jeff Skiles, played by Aaron Eckhart with a mustache, had to grapple with their horrifying reality without warning.

At his request, investigators delayed the simulator's decision-making process down by 35 seconds. With that extra time for the human minds to come to terms with the situation, the simulator determined the plane could not have made it to any airport, but would have crashed in densely populated Queens or suburban Jersey.

In an interview with Newsweek, Hanks said he respected and understood the NTSB officials whose hard questions make them the movie villains.

"That's their job. They are a fact-finding body," he said. "If the facts had come out that were beyond Sully's recollection of what happened, thats their job to find out. To their credit they did everything right. Their last hearing was 'boy you were really great, you did the right thing.' "

Hanks said that the "most evocative scene" for him was one of anonymous men and women in suits around a conference table high in a New York building looking up and noticing a plane flying way too low just outside their window. The scene is underplayed, silent, grave.

"Those people in there meeting, seeing this low-flying commercial airliner coming in; what goes through their heads," Hanks said.

Eastwood may be a rock-ribbed conservative, but he's managed here—as in his other late in life films—to weave subtlety into what could have been a patriotic cartoon.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Nina Burleigh is Newsweek's National Politics Correspondent. She is an award-winning journalist and the author of six books. Her last ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.