It is one of the great contradictions of the American psyche that we embrace nostalgia but shun history. The 1960s are the perfect example of that paradox. We have learned all the easy lessons of that era, whether from Barry Goldwater or Jerry Garcia, while largely neglecting a sober, self-critical assessment of that age, when so many different segments of society—movement conservatives, ethnic minorities, suburban women, the restless young—clamored for revolution. For some crucial but ill-defined reasons, most of those yearnings remained unmet and, in fact, remain so to this day. Someone spiked the punch, maybe. When we awoke, a peanut farmer from Georgia was hectoring us about malaise from the Oval Office.

"The Summer of Love Experience: Art, Fashion, and Rock & Roll," a new exhibition at the de Young Museum in San Francisco that runs until August 20, is an earnest and generally successful attempt to treat seriously, and somewhat critically, a decade that continues to define American life. Conservative columnist John Podhoretz, for example, called the 2016 presidential contest between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton "the election of the Sixties Throwbacks." The de Young show is a throwback too, but a far more pleasant one than last fall's political slog. With its fringe vests, Grateful Dead posters and disorientingly trippy videos, "The Summer of Love Experience" is less a show of fine art than anthropology, a testament to how curious we remain about the varieties of Homo sapiens that converged in San Francisco in the late 1960s.

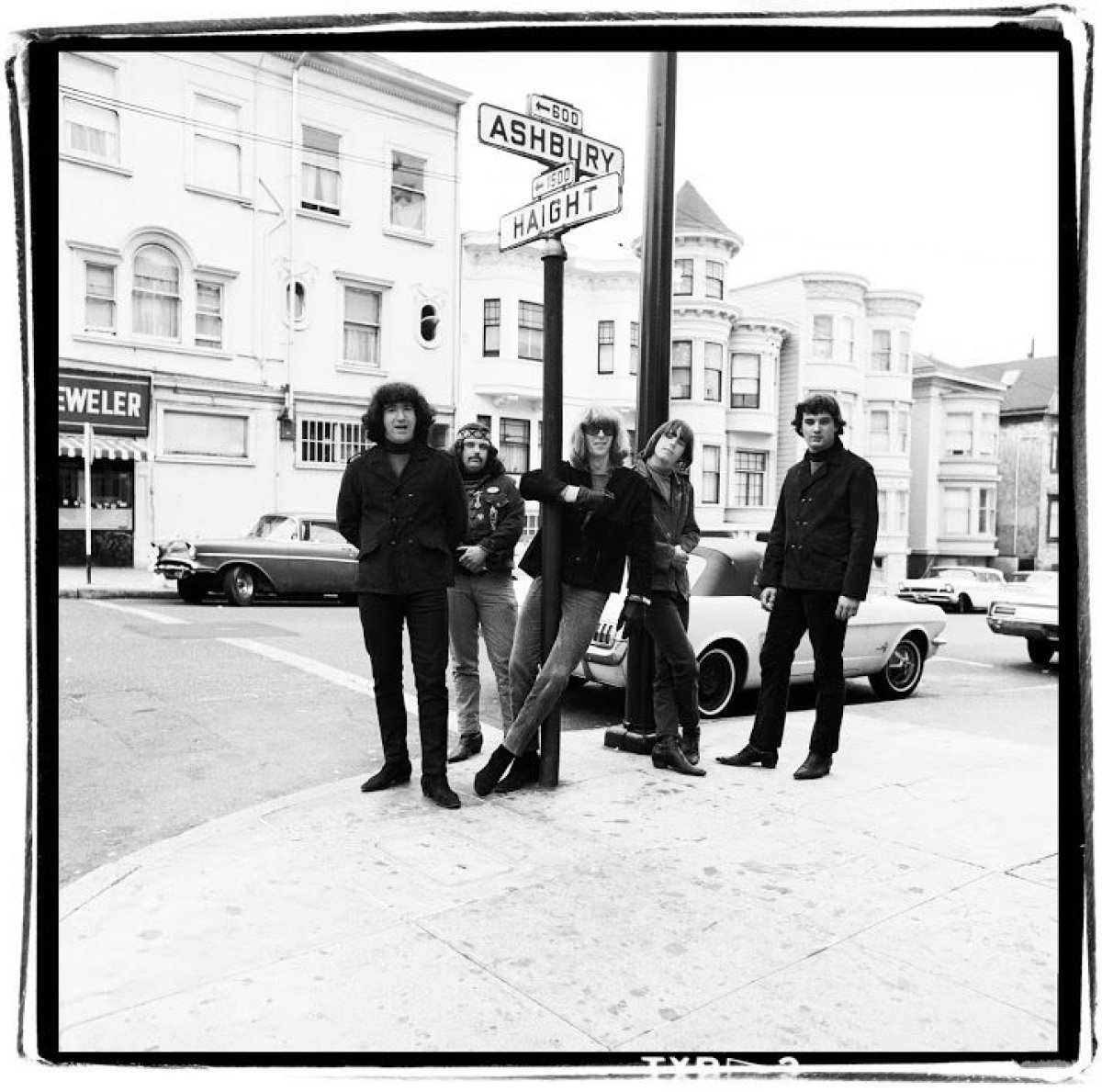

The Summer of Love wasn't a precisely defined event like Woodstock, though the Human Be-In that took place on January 14, 1967, in Golden Gate Park—not very far from where the de Young stands—is widely thought to be the starting point of that strange, enchanted season. The Grateful Dead played, Allen Ginsberg performed his shambolic dance, Timothy Leary issued his famous edict to "Turn on, tune in, drop out." If the movement didn't have a beginning, it did have an epicenter—at the intersection of Haight and Ashbury streets, where that summer some 100,000 young people converged to overthrow capitalism or just get laid.

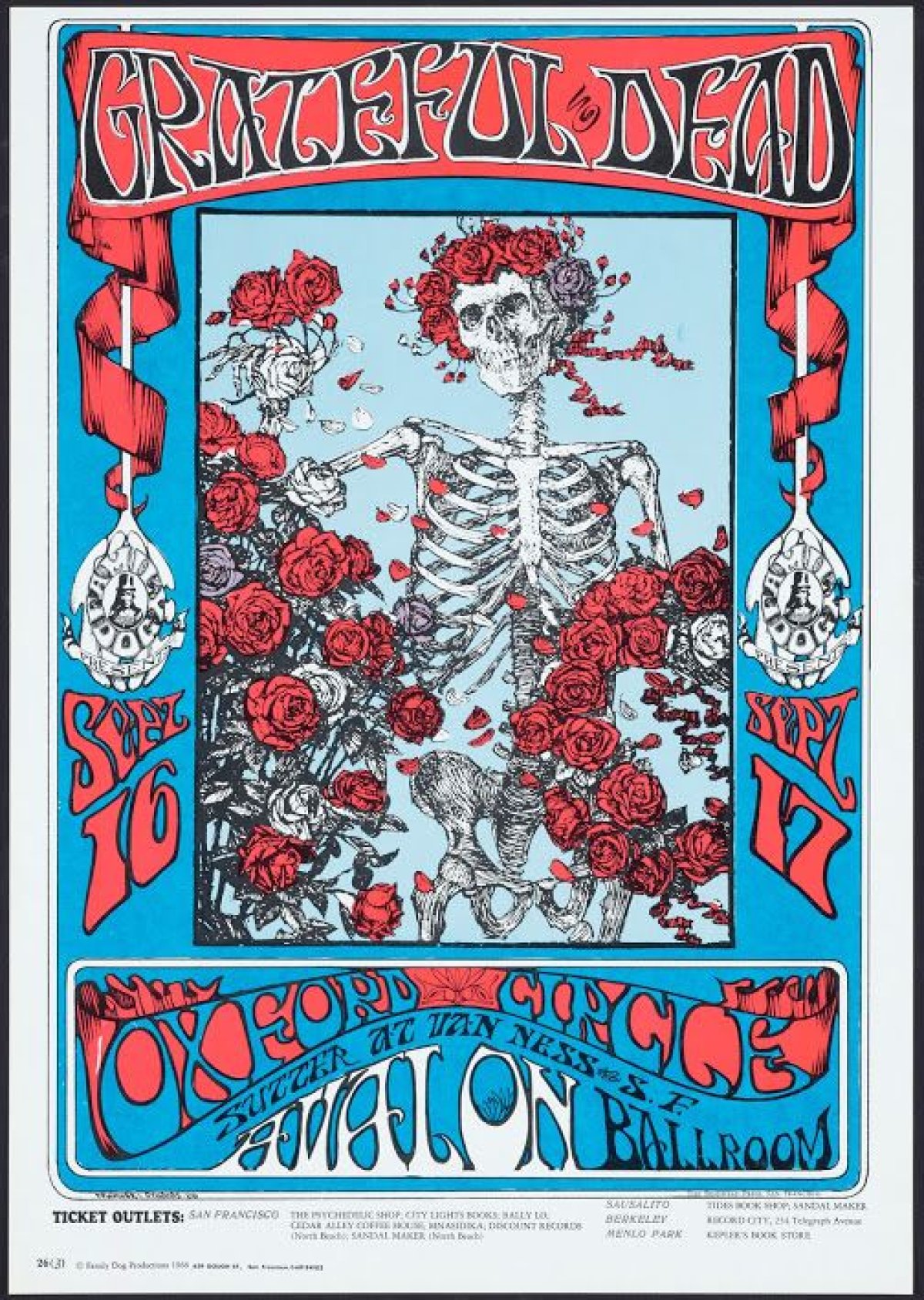

Music was central to the Summer of Love, a fact that would seemingly pose a challenge to an art exhibition. It happened, however, that the anti-corporatist revolutionaries of the Haight managed to turn the most corporate of practices—that is, advertising—into an art form for music. This was done almost entirely through ubiquitous posters that borrowed freely from surrealism and art nouveau to advertise shows by Janis Joplin or the Grateful Dead. The best of them, particularly those done in the service of the Dead by Stanley Mouse and the Wes Wilson posters for shows at the Fillmore Auditorium, achieve an original aesthetic. Many do not, however, especially when presented in relentless collage, threatening to turn the exhibition into a giant head shop.

Related: San Francisco Gets Gooped

Clothes were central to the San Francisco experience of the 1960s. In the years since, hippie style has devolved into loose robes and tie-dye, a stoned sloppiness that is a kind of anti-style. "The Summer of Love Experience" makes the case that the fashion associated with the Haight-Ashbury scene was more varied and complex than popular culture today suggests. Designers borrowed from Native American culture by incorporating leather and fringed ends. A port city, San Francisco also had access to Asia and Latin America, from which designers borrowed colorful, nonlinear designs. A homegrown clothes company that once outfitted the Gold Rush—Levi's—supplied the denim that is perhaps most closely associated with that movement.

Although the exhibit's swirling, loopy colors practically demand social-media sharing, the exhibition curiously downplays the connection between the idealism of the hippies and the idealism of the techies, who now claim San Francisco as their own. For an exhibition that wants so badly to posit the Summer of Love as a lastingly relevant phenomenon, this is an inexplicable omission.

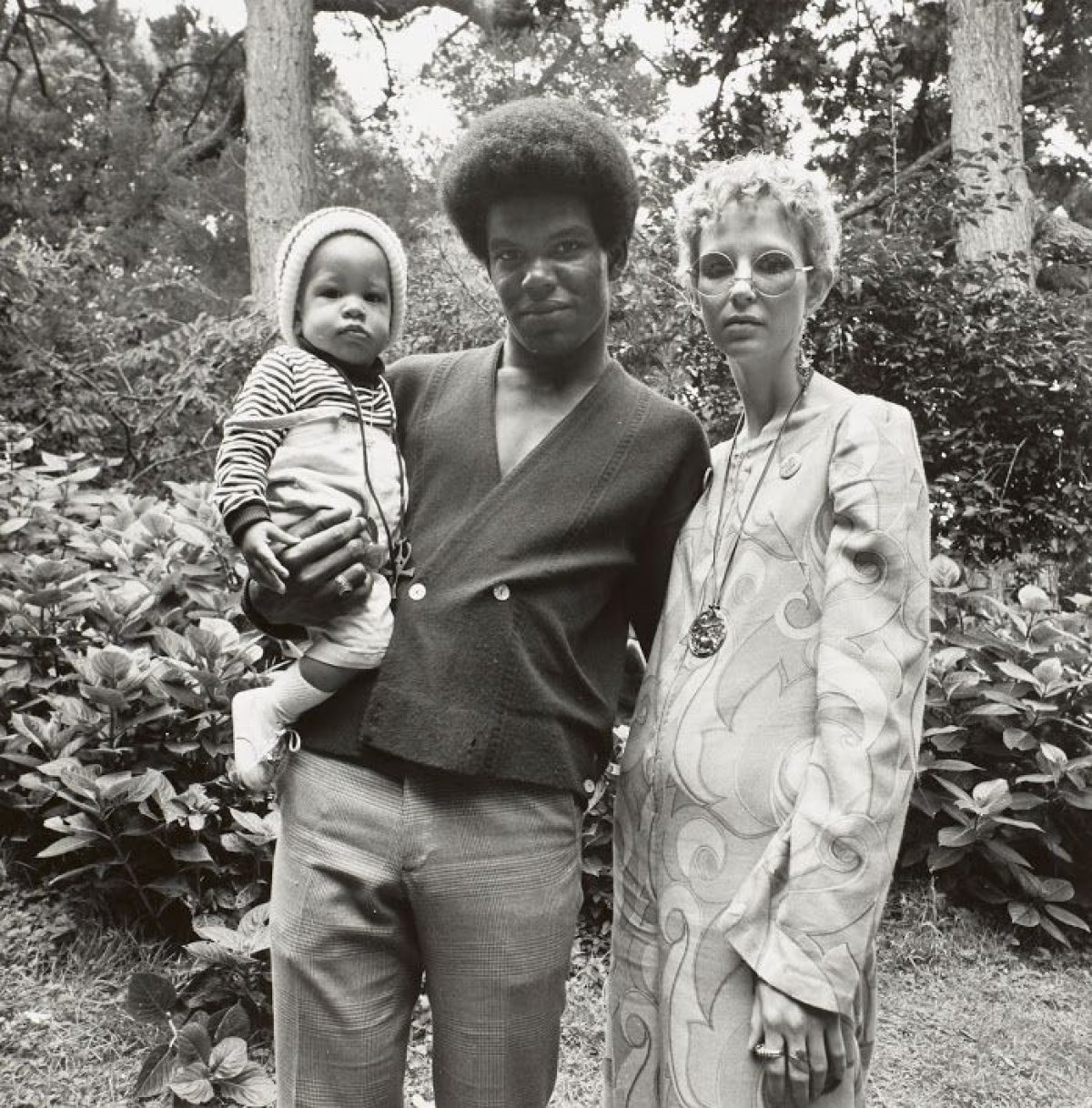

The exhibition's artistic high point is the collection of black-and-white photographs by Elaine Mayes and Ruth-Marion Baruch, which capture the complexity of the Summer of Love without any mythologizing. Mayes, in particular, seemed to convey the vulnerability of the young men and women who flocked to the Haight, only to find that it could be as cruel as whatever town they'd escaped from. Baruch provides an important chronicle of the Black Panthers, then forming across the bay in Oakland as a furious rejoinder to hippie-dippie idealism.

On the Thursday afternoon that I visited, the exhibition was crowded. Some of the well-heeled attendees looked upon the exhibits with a chuckling familiarity that suggested they were there for the real thing; others were clearly too young to remember San Francisco before the tech boom, never mind the city in its freewheeling days of yore. The profusion of languages (Spanish, German, Hindi, Midwestern) was pleasant aural proof that the fascination with the 1960s remains a worldwide phenomenon.

Outside the museum, lampposts are adorned with fake street signs meant to evoke the intersection of past movements and tropes with present ones: hippie meets hipster, civil rights movement meets Black Lives Matter. This is almost more instructive than anything else in "The Summer of Love Experience," cleverly making the argument that "woke" millennials have borrowed plenty from the angel-haired masses of Haight-Ashbury.

And there were warnings here too, on the walkways leading up to the de Young, where buttons from the 1960s have been re-created in the form of circular slogans pasted on the brick-clad path. "Equal Rights," one says. To achieve something like that would have required a sustained, collective focus immune to all forms of distraction. Yet another button offers quite different, far narrower advice: "If it feels good do it!"

Or maybe don't. The 1960s failed as a social movement because its main practitioners surrendered their moral seriousness, which is why the subsequent decade was rife with delusive hedonism: mood rings, disco, coke, self-help, jazzercise. It took a few years, but the Summer of Love soured into a cold, wet autumn.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national affairs.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.