A super-sensitive, accurate spit-based test to detect HIV could be around the corner. Stanford researchers have developed a test that was 100 percent accurate in one study involving a handful of patients, according to findings published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). If these results are confirmed in much larger studies, the test's proponents believe it could be an important tool in the fight to eradicate HIV.

Multiple oral HIV tests are already on the market, including one that can be done at home. However, researchers say theirs is far more sensitive and can detect infections sooner—possibly as soon as two weeks after a person is exposed.

The advantages of using spit rather than blood to diagnose HIV is obvious—you can't be infected by the spit of a person who is HIV-positive. People are also generally much more willing to give you their spit than their blood, Dr. Nitika Pant Pai, an HIV testing researcher at McGill University who was not involved in the research, told Newsweek. "The beauty of oral testing is the non-invasive part of it," she said, especially for people who might be particularly hesitant to have a blood draw done like children, young adults and pregnant women. (The paper noted the test might be useful for population screening in contexts where blood-based collection might be ill-advised, like prisons, or among people who might be particularly difficult to draw blood from, including infants and people whose veins are compromised due to repeated injections.)

Blood and saliva are actually related. You can find most of the stuff you find in your blood—in very low levels—in your spit. (The reason HIV is not transmissible through spit is because saliva itself can mess with the virus.) However, the levels of HIV antibodies that are detectable in spit are so, so low—and there's no getting around that. "You can't amplify a protein. There's no way to amplify a protein. But if you can somehow convert a protein to a DNA signature, then you can amplify the DNA," study author and Stanford University chemist Carolyn Bertozzi said. (Bertozzi is also a researcher at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.)

Thankfully, we've got a way to amplify DNA—the polymerase chain reaction, also known as PCR. That part is something that any biology student with a properly equipped lab could do. However, Bertozzi's lab is currently the only place where the rest can be done.

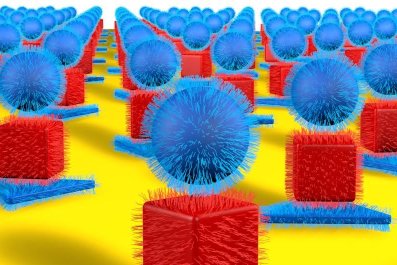

Her team's technique sticks a piece of single-stranded DNA onto proteins, called antigens, to which HIV antibodies will bind. If antibodies to these proteins are present in a person's spit—meaning if they are infected with HIV—the antibodies will stick and start to form a clump of antigens. Because these antigens have pieces of DNA on them and because they're so close together, Bertozzi and her team can actually make the single strands of DNA bind together—giving the PCR something to amplify and eventually for the test to detect. (The technique is properly called antibody detection by agglutination-PCR.)

Being able to amplify even the smallest indication that a person is infected with HIV could translate into earlier detection and diagnosis. However, this study is far from conclusive proof that the test works. Though the accuracy of the test was 100 percent, it was only tested on about four dozen cases. There would need to be much, much larger studies before it could be used more widely. ("I would be happy to collaborate with them!" Pai laughed.)

And if you're not directly looking for the virus, there's a chance you might miss it. In order to find antibodies, the immune system has to produce antibodies; people whose immune systems have a particularly weak response or whose immune systems haven't had enough time to react to the virus wouldn't get a positive result. The time it takes for a test to be able to detect the immune system's response to a virus is called a "window period;" the current window period for oral tests can be up to several weeks long.

"This is a very intriguing protocol that they have developed. I think it's exciting, I think it has a lot of potential," said Dr. Daniel Malamud, director of the HIV/AIDS research program at NYU's College of Dentistry who was not involved in this research. (Malamud did sit on the scientific advisory board to Epitope, which developed another oral fluid test for HIV, Orasure. He once held stock in that company, which he has since sold.)

However, Malamud said he did not believe it would replace the current oral screening tests "based on cost and ease of use." Instead of replacing current oral tests, some of which are designed to be used at home, Malamud said he could see it being a tool geared mostly toward scientists at public health laboratories.

In theory, this technique could work for more than just an HIV screening tool. The Gates Foundation is interesting in using it to develop a test for measles, Bertozzi said, and she and her colleagues have a few other applications in mind and have started a company, Enable Biosciences, to develop them. Optimistically, Bertozzi thinks they may be ready to bring the HIV test to the wider world in the next 18 months.

In theory, a screening test could be extremely important to any efforts to completely eliminate HIV. However, what would need to come first would be an effective vaccine—and we don't have that yet. "We just need a good vaccine, and we need to understand how to deploy it," Bertozzi said. "And having a good oral test is part of the deployment."