Less than a quarter of the way into the new school year, Diane Tirado, an eighth-grade teacher in Port Saint Lucie, Florida, was fired from her position—a position, she claimed, she would still have if it wasn't for the school's "no zero" policy.

Tirado was hired over the summer to teach eighth-grade social studies at West Gate K-8 School. She's amassed almost 17 years of teaching experience across multiple grades, both online and in a classroom.

In the last five years or so, Tirado said she found that most districts had adopted a "no zero" policy whether it was written in the handbook or an unspoken rule among educators. Originally designed as a "helping hand" to keep kids from falling too far behind, the policy was to not give any student a grade of zero, as long as they turned in the assignment and tried.

However, Tirado told Newsweek that West Gate's policy is an extension of the original and prevents teachers from ever giving a student a zero, even if they never complete the assignment. The parent handbook on the school's website explained that students in grades three through 12 will receive letter grades to indicate their progress.

A grade of "I" with a percentage of zero is listed in the chart and written right below the outline of grading, in all capitalized, red letter is "NO ZERO'S—LOWEST POSSIBLE GRADE IS 50%."

Tirado claimed that she was never explicitly told about the policy, and when some students didn't turn in a two-week take-home project by the deadline, she put stars in the grade book. The stars, she told Newsweek, act as placeholders until the end of the marking period when she intended to give students a chance to turn in assignments they missed for credit. As a policy, she would deduct 10 percent for it being late, but it would still give students a chance to receive a proper grade.

"Grades weren't due for another three or four weeks. I leave things as stars which are [considered missing assignments] until a week before grades go in," she explained. "Every teacher does it. We don't want kids to fail. We want kids to succeed."

However, she said the school wanted her to automatically input a grade of 50 percent, despite having no assignment to grade, as some kids didn't turn the project in. Tirado said she expressed her opinion about the policy with the teacher's union and her assistant principals.

"If we are creating people of entitlement to the point where they're expecting something for nothing what kind of world do you have?" she wondered.

In a statement to Newsweek, St. Lucie Public Schools rebuked Tirado's claim that there is a policy that prevents teachers from giving students a grade of zero if no work is turned in. The school added that the zero on the grading scale in the handbook is there to indicate work "not attempted" or "incomplete."

St. Lucie Public Schools explained the district uses the Uniform Grading System, which has numerical grades of 100 to zero and grade point averages from four to zero. The school pointed to the work of Dr. Douglas Reeves in "The Case Against Zero" and said the five point grading scale is more accurate and better for students.

"The work of Reeves and others around effective grading practices is supported by the district; however, it is not a requirement," the school said. "This practice still results in a normal grading curve requiring student mastery of content."

When Tirado was told to input the minimum grade before the marking period was over, she argued that if students got 50 percent without turning the assignment in, a student who received 50 percent for completing the assignment should really be given 100 percent.

"Why should they work hard when they know they're going to pass?" Tirado told Newsweek. "A kid looks me in the eye and says, 'I don't have to do anything and you have to give me a 50.'"

Another issue of contention Tirado had with the school was the topic of extended time for students with Individualized Education Program. The school wanted Tirado to give students with IEPs extended time for the two-week project.

However, she explained that the extended time allowance is for in-class assignments and exams, not take-home projects. Tirado reasoned that giving students with IEPs double the time to complete the two-week assignment meant that a different project due in January couldn't be required to be completed until July when school isn't in session.

St. Lucie Public Schools told Newsweek that the school deemed Tirado's refusal to incorporate IEP accommodations, mandated by federal law, to be "defiant and put students at risk."

Tirado claimed that she was not given a specific reason she was being fired during a meeting with the two assistant principals. She deducted that her issue with the "no zero" policy was at fault since she was always on time, if not early, and had surpassed the minimum requirement for grades being entered.

"Ms. Tirado was released from her duties as an instructor because her performance was deemed substandard and her interactions with students, staff and parents lacked professionalism and created a toxic culture on the school's campus.… Her dismissal was not a result of grading issues." St. Lucie Public Schools told Newsweek.

The school added that during her time at West Gate, the school received numerous complaints and concerns from parents and college. New information shared with school administrators also prompted an investigation of possible physical abuse, according to the school's statement.

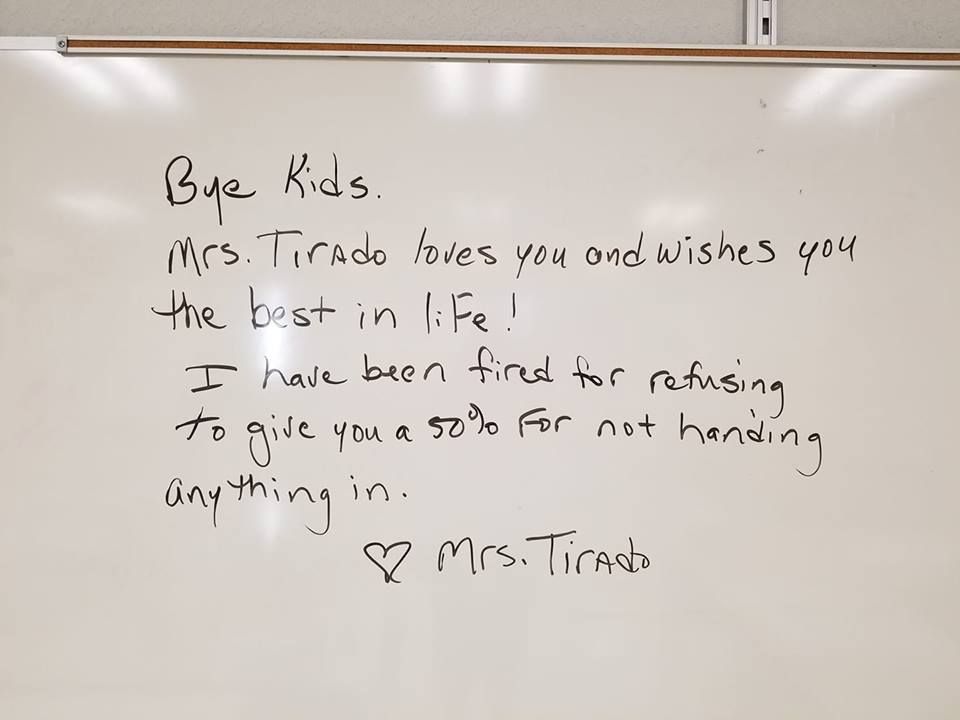

Following her termination, Tirado posted a photo on Facebook of a message she left on her classroom dry-erase board. She explained to kids that she wished them the best in life but had been fired for refusing to give 50 percent for work that wasn't handed in. After receiving support from fellow teachers and people she'd never met, Tirado posted that she took on this fight because the policy is "ridiculous."

"Teaching should not be this hard. Teachers teach content, children do the assignments to the best of their ability and teachers grade that work based on a grading scale that has been around a very long time," she wrote.

Given that she had only recently been hired and was still in her probationary period, Tirado told Newsweek that she doesn't have very many legal options available. At this point, she explained that she feels she's done everything she can and hopes the National Education Association, a nationwide labor union, picks up this fight.

This article has been updated to include the response from St. Lucie Public Schools.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jenni Fink is a senior editor at Newsweek, based in New York. She leads the National News team, reporting on ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.