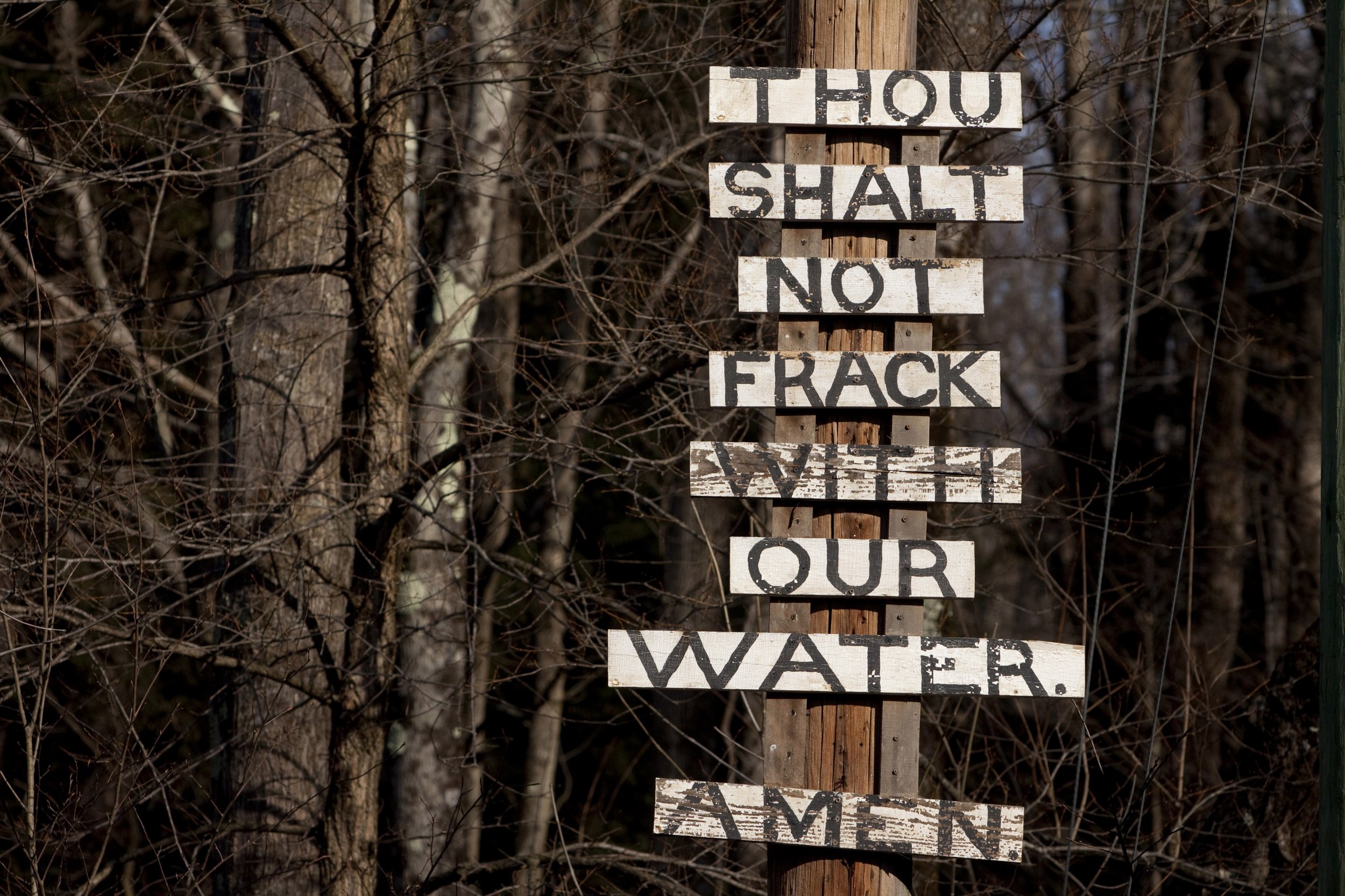

As the U.S. fracking boom continues to expand, tapping vast deposits of previously unreachable oil and natural gas, scientists, regulators and even the industry itself still do not know much about fracking's impact on human health or the environment. Study after study has highlighted the lack of toxicity information available on fracking fluid—the mix of chemicals, water and sand injected deep into the ground to fracture oil- and gas-trapping rock.

Now a new study, presented Wednesday at the national meeting of the American Chemical Society, says that out of 190 commonly used compounds, hardly any toxicity information is available for a whopping one-third of them. In addition, another eight fracking fluid compounds, the researchers found, are proved to be toxic to mammals.

William Stringfellow, an ecological engineer at the University of the Pacific and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, says he and his team embarked on the review of fracking chemical databases on reporting websites like FracFocus.org to help resolve the public debate over the controversial drilling practice's safety.

"The industrial side was saying, 'We're just using food additives, basically making ice cream here,'" Stringfellow said in a statement. "On the other side, there's talk about the injection of thousands of toxic chemicals. As scientists, we looked at the debate and asked, 'What's the real story?'"

As it turns out, many components of fracking fluids are indeed nontoxic and food-grade materials. But even these require adequate treatment before they can be disposed of without harming the environment, Stringfellow says.

Other components are more threatening.

"There are a number of chemicals, like corrosion inhibitors and biocides in particular, that are being used in reasonably high concentrations that potentially could have adverse effects," Stringfellow says. "Biocides, for example, are designed to kill bacteria—it's not a benign material."

A previous study, published in 2013, found that fracking fluids contain endocrine disruptors, which mimic estrogen and can contribute to hormonal diseases, cancer and infertility. Stringfellow's study makes no mention of endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

Part of the reason that information on the toxicity of fracking fluid chemicals is so hard to come by is that in some cases the exact composition of the fluid and the chemicals used are protected as trade secrets and therefore not reported by the company that makes them.

But that is slowly changing. More and more states are adopting rules that mandate some disclosure of fracking fluid components. California, for example, does not offer trade secret protections to fracking fluid manufacturers. However, some states are moving in the opposite direction. North Carolina earlier this year made disclosing trade-secret-protected fracking chemicals a felony.

Stringfellow's study concludes with a plea for more research on fracking fluids in all the scenarios for use during drilling, including before they are injected and when they flow back to the surface after injection. Environmental hazards, the researchers write, cannot be understood until the fate of the chemicals are analyzed in their various complex environmental contexts.

"[D]ata gaps concerning toxicity, biodegradability, physical constants, and concentrations of use should be addressed so that accurate and informed environmental and health assessments can be made," the researchers write.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Zoë is a senior writer at Newsweek. She covers science, the environment, and human health. She has written for a ... Read more