This article first appeared on the Dorf on Law site.

I'm a little ashamed to admit that I already miss the Mooch.

Unlike Spicer, Huckabee Sanders, Conway, and the rest of that robotically mendacious crowd, Anthony Scaramucci, the effervescent but sadly evanescent White House communications director, appears to be occasionally capable of unprogrammed, human-like opinions.

Nevertheless, only after the Mooch was dismissed for delivering his must-read interview-rant, could I (momentarily) pull myself out of reach of the daily splattering of untreated sewage that passes for White House communication.

I decided to try to think about where Trump and the Republicans are heading.

I started by pondering the already trite Presidential conundrum: "Who would you rather have as President, the incompetently evil and deranged Trump or the competently evil and theocratic Pence?"

For the purposes of moving on, I accepted Frank Rich's sunny prediction that, in the wake of a Trump impeachment or resignation-under-scandal, the newly sworn-in Pence would be so tainted that he would be rendered ineffectual, with potentially cleansing elections around the corner.

It's not about Trump, stupid

The real story has been, since day one, not Trump but the Republican Party's enabling and facilitating of Trump's destructive behavior and policies.

On one hand, there are numerous op-ed articles noting the Republican Party has become so ideologically extreme in the last 30 years that it is doomed for extinction. While the shedding of long-term conservative party members such as George Will and Joe Scarborough provides some hope in that regard, their departures appear to be more anti-Trump than disagreement with the Party's increasingly wacko positions.

Our attention must thus turn to that other political party, which will have to actually win elections instead of sitting forlornly on the sidelines wondering why its often milquetoast candidates lose even in districts Trump barely won in November.

What would the Democrats have to do to wallop the Republicans in the 2018 and 2020 elections?

The most recent official Democratic Party response has been to propose a "new vision" ideologically more to the left in an attempt to re-brand the Party. It's hard to imagine that alone will cause a significant shift in voting patterns.

What might convince the electorate that these Democrats are somehow an improvement on the previous version?

A domestic inspirational precedent

I sought inspiration from two huge electoral triumphs. Since the current Democratic share of national and state government offices by some accounts is lower than it has been since the 1920s —and because I recently finished reading the first volume of Robert Caro's biography of Lyndon Johnson--the first was the Franklin Roosevelt-led 1932 national elections.

That year, more than 30 percent of House seats turned over, in contrast to the less than 15 percent in each of the previous 4 House elections. 1932 was the first of 3 successive elections in which the number of Democratic senators went from 47, to 69, and to 76 by 1936.

It is still stunning to reflect that the Democrats crushed Herbert Hoover's Republicans so thoroughly that they established congressional majorities lasting essentially from 1933 to 1994. Within that 62-year period, the Republicans only managed to gain control of the House for 4 years, and of the Senate for a total of 10 years.

It is, of course, fatuous to expect anything remotely comparable in the upcoming mid-term, non-Presidential election, which fortunately is not occurring in the midst of a horrible economic depression. But the lesson I drew from Caro is regarding how FDR and the Democrats presented themselves to the exhausted country.

Clear goals, not programs

In Caro's telling, FDR and the Party did not simply run as "We're not Hoover," nor offered a catalog of specific programs. They outlined clear goals, but presented themselves as essentially willing to actively try anything —obviously involving massive government intervention-- to solve the country's major economic problems.

This stood in stark contrast with the single-minded passive focus of Hoover's Republicans on balancing the budget.

Democrats are currently flirting with the idea of coalescing around offering a serious national health plan, like every other single developed country has had for decades. Guaranteeing truly universal health care, and cutting costs by streamlining the ridiculous health insurance bureaucracy, with at least a public option, would be a clear goal.

While there may be disagreements about the political tactics the Party should take to get there, it seems obvious that clear advocacy of a Medicare-for-all as a goal, rather than mealy-mouthed advocacy of tinkering with the ACA (who votes for tinkering?), would start to set them apart from the Republicans.

A foreign inspirational precedent

Another, more timely example of electoral triumph is that of Emmanuel Macron and his party in France. Not only did he personally triumph over the candidates of the traditional parties, but in the subsequent legislative elections his party won a clear majority of seats.

In fact, fully 75 percent of the seats in the lower House (Assemblée Nationale) turned over. To put that figure in context, there was 40 percent turnover seen in the previous French election in (2012), and 25 and 34 percent in the two before that.

Do these numbers have any meaning in the US context, as we know that France is not the US, and that their parliamentary system differs significantly from the US system?

We might first conclude no, since in the US elections in 2016, a Soviet politburo-level 97 percent of House incumbents were re-elected.

But the French parliamentary elections have 5 year terms, vs 2 years in the US House, so a fairer comparison might be to look at how many US Representatives re-elected in 2016 had been in office 6 years earlier (i.e., in 2010). The answer is 57 percent , for a 43 percent turnover during that time period.

For good measure, the average turnover for US Senate seats (also a 6 year cycle) in the past 7 elections has been 38 percent . So in both countries about 40 percent turnover is normal every 6 years (pre-Macron).

There may be some lessons here, because Macron, like the Democrats, was trying to portray himself as "something different." Without being reductionist in explaining why Macron won, I think it is valuable to look at three of the wholesale changes Macron made in the party and how it chose its nominees for parliament.

A new party. Or at least a new name

First, he created a whole new party out of disaffected individuals from other parties.

The renaming and restructuring of political parties seems to be a French speciality. For example, the political party of Jacques Chirac and Nicolas Sarkozy (L'Union pour un mouvement populaire [ UMP]) was only created in 2002, and Sarkozy himself led its subsequent re-branding as "Les Républicains" just a few years ago.

This doesn't seem likely to happen with the Democrats, although maybe it should. And in fact, in the US, when long-established companies really want to change their brand perception, whether to escape the taint of scandal, following acquisition of another company, or to reflect that their core business really has changed, they change their name.

More women

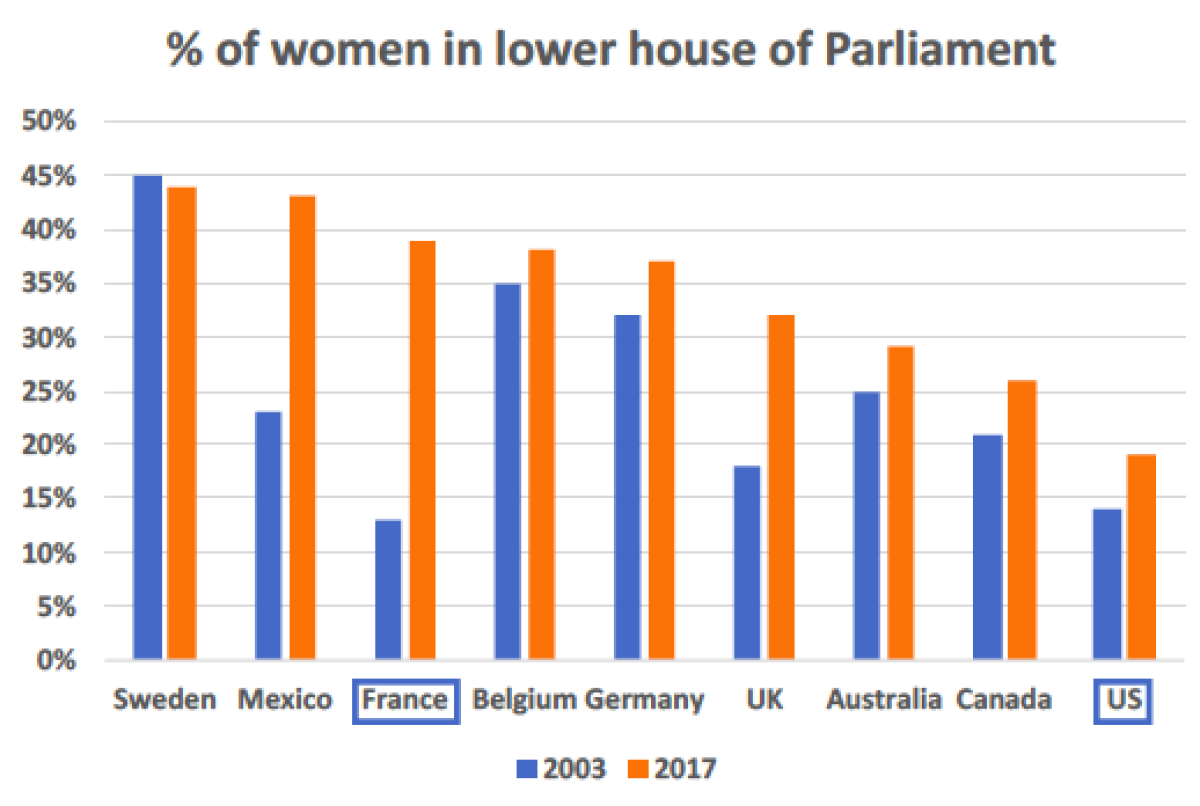

Secondly, and more concretely, Macron was fully committed to gender parity for his party's candidates to parliament (as well as in his cabinet ). The following figure depicts the male-female ratios in selected lower house of Parliaments and the US House of Representatives in 2003 and 2017.

Unfortunately, the US, unimpressive 14 years ago, today looks pathetic compared to France or its other peers in this rather fundamental measure of progressiveness.

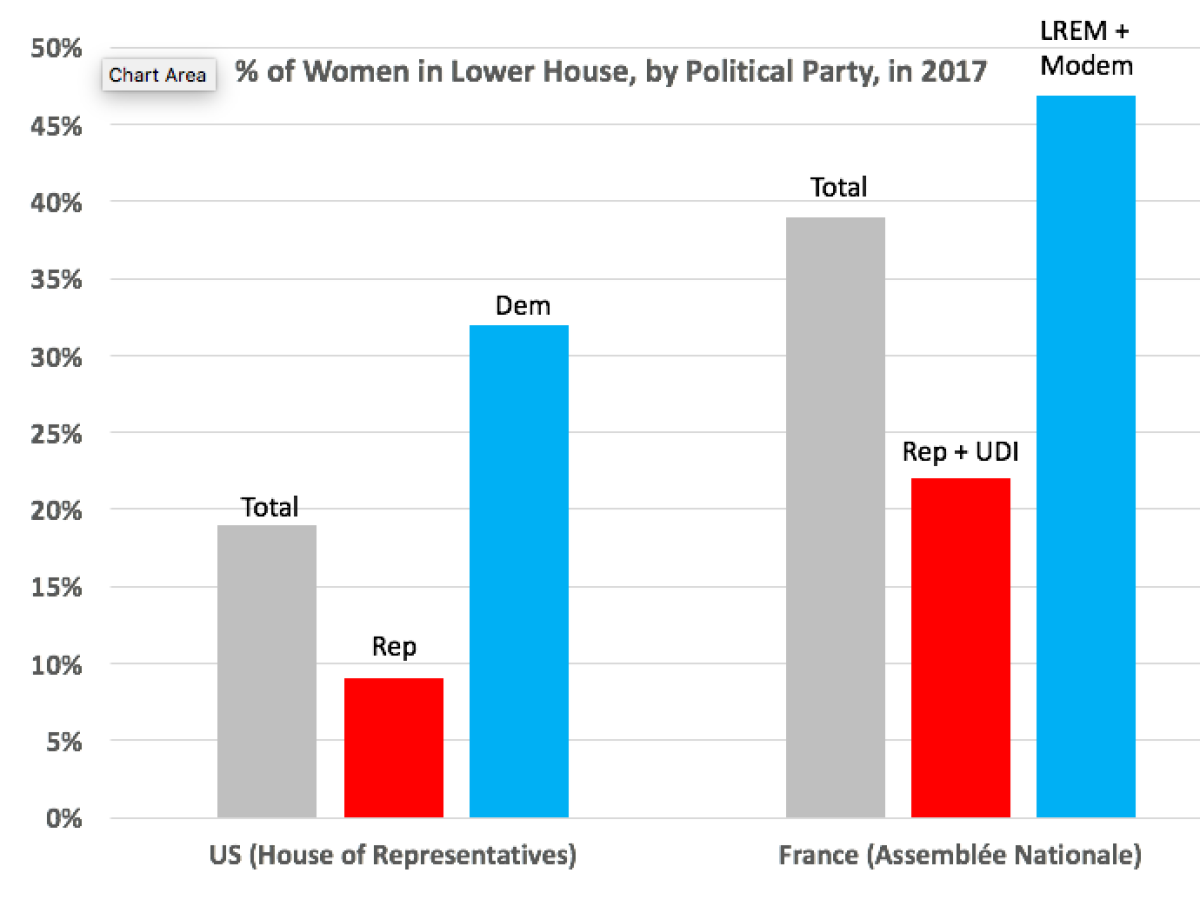

I would be delighted to attribute this solely to the Republican house members. But the following figure shows the male-female ratios in the US House of Representatives vs those of the French Assemblée Nationale in 2017, by political party (Macron's coalition is LREM + MoDem, and Les Républicains campaigned alongside the UDI):

It is likely no coincidence that the meager proportion of Republican representatives who are women is similar to the proportion of Trump cabinet members who are women (2/15 = 13 percent). But with 2/3 of their representatives being male, the Democrats also have a way to go to reach parity.

There are, of course, fundamental differences in how parties choose their candidates in various countries, and there is even a law in France mandating male-female parity in parliamentary nominations (the Républicains + UDI have preferred to pay million-euro fines rather than achieve that). Plus the US frenetic election cycle of every 2 years makes it quite difficult to abruptly change the House nominees.

But if the Democrats are serious about being a progressive party, why not openly declare a clear goal of male-female parity within the next few years?

Younger candidates

A third way in which the 39-year old Macron directly changed the face of his party was by nominating and electing a much younger set of MPs (average age 45.5 years) than the previous Assemblée Nationale (average age 54 years). This was also significantly younger than those elected within the largest opposition party, Les Républicans (average age 52 years).

There have been a series of articles contrasting how old the Democratic House leadership is (average age 71) with how young, for the most part, their counterparts in the Republican party are (average age 49). It has been surprisingly difficult, however, to find any article describing the average age of House members in 2017 by party.

After some manual calculations based on individual member birth year, it turns out that the average Democratic representative turns 61 this year, and the average Republican representative 57.

For a party looking to put on a fresh face, not to mention galvanize the younger voters (meaning under 40), this is probably not a winning strategy. I haven't read anywhere that putting up younger candidates for Congress is a priority for the Democrats.

It is too much to dream for an FDR-like or even Macron-like landslide that will send the Republicans into congressional oblivion in 2018 and 2020 for the next 60 years. But it will be nice if the Democrats make a serious effort.

Changing the name, aiming for gender parity, and recruiting younger candidates would be a start.

William P. Hausdorff works in international public health and vaccine development, initially with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control/Agency for International Development and most recently within the vaccine division of a major pharmaceutical company. He is a freelance consultant based in Brussels (billhausdorff3@gmail.com).

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.