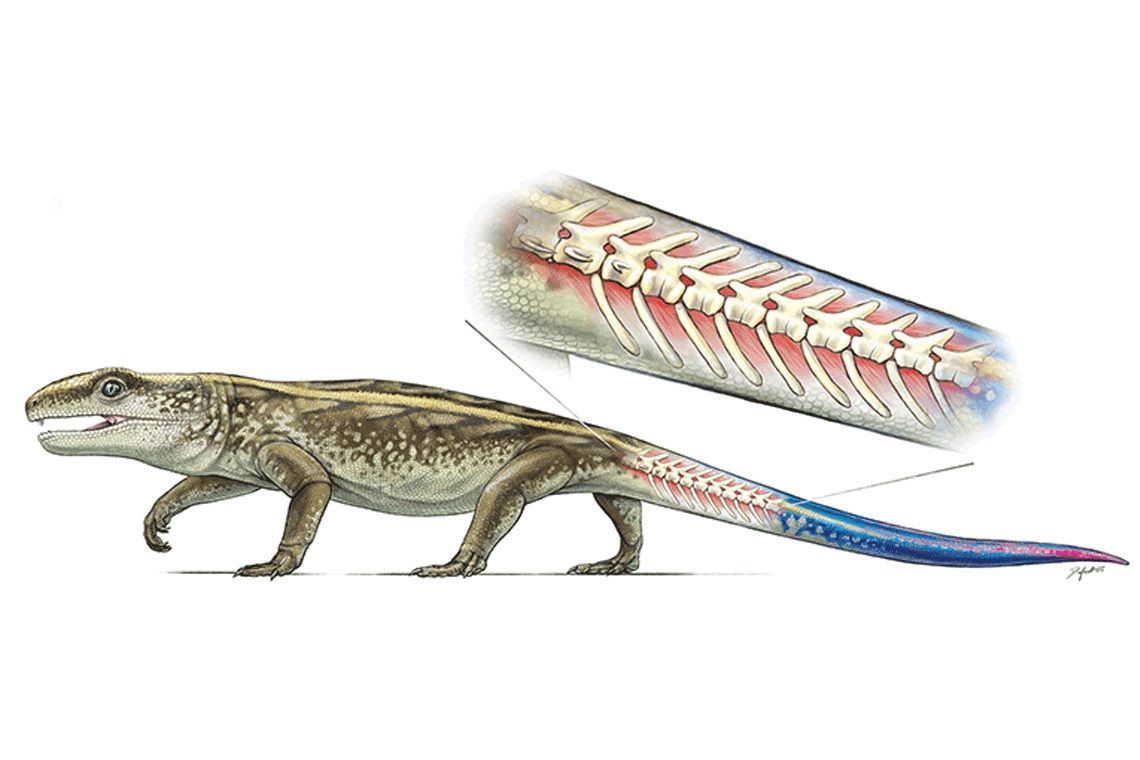

An analysis of 70 chunks of tail bones has uncovered a special characteristic of an ancient reptile known as Captorhinus. The ancient fossils reveal it had an escape trick to get away from its larger, meat-eating predators: it detached its tail and scurried away.

University of Toronto researchers led the study, which was published Monday in Scientific Reports. The tiny reptile—a mere 4.5 pounds—lived 289 million years ago, but the so-called "cracks" in its tail helping it run away made the reptile rather successful. By the end of the Permian period 251 million years ago, captorhinids could be found across Pangaea, the ancient supercontinent.

The feature that aided its success is comparable to a paper towel. The perforated line keeping paper towels attached but easily pulled apart is how the bone structure of these reptile tails were built. "If a predator grabbed hold of one of these reptiles, the vertebra would break at the crack and the tail would drop off, allowing the captorhinid to escape relatively unharmed," Robert Reisz, biology professor at University of Toronto Mississauga and co-author, said in a statement.

Though the trait is beneficial for survival, it died out out of the fossil record eventually. Some 70 million years ago, the trait reappeared in lizards and many current species have the trait, too. "Like many present-day lizard species, such as skinks, that can detach their tails to escape or distract a predator, the middle of the tail vertebrae had cracks in them," lead author and postdoctoral student Aaron LeBlanc said in a statement. This small reptile, however, is the oldest known species to have this tail trait.

The researchers also discovered that the reptiles' tails differed as they aged. Adults would grow out of the detachable tail characteristic—the cracks often appeared like they were fused together. Researchers say this is logical since the youth were most at risk of being eaten. So it seems, per the evidence from these fossils, the small size didn't stop captorhinids from becoming the most common reptile of their time across Pangaea.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Sydney Pereira is a science writer, focusing on the environment and climate. You can reach her at s.pereira@newsweekgroup.com.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.