Researchers have identified a new, tiny species of millipede in 99-million-year-old amber from the southeast Asian nation of Myanmar.

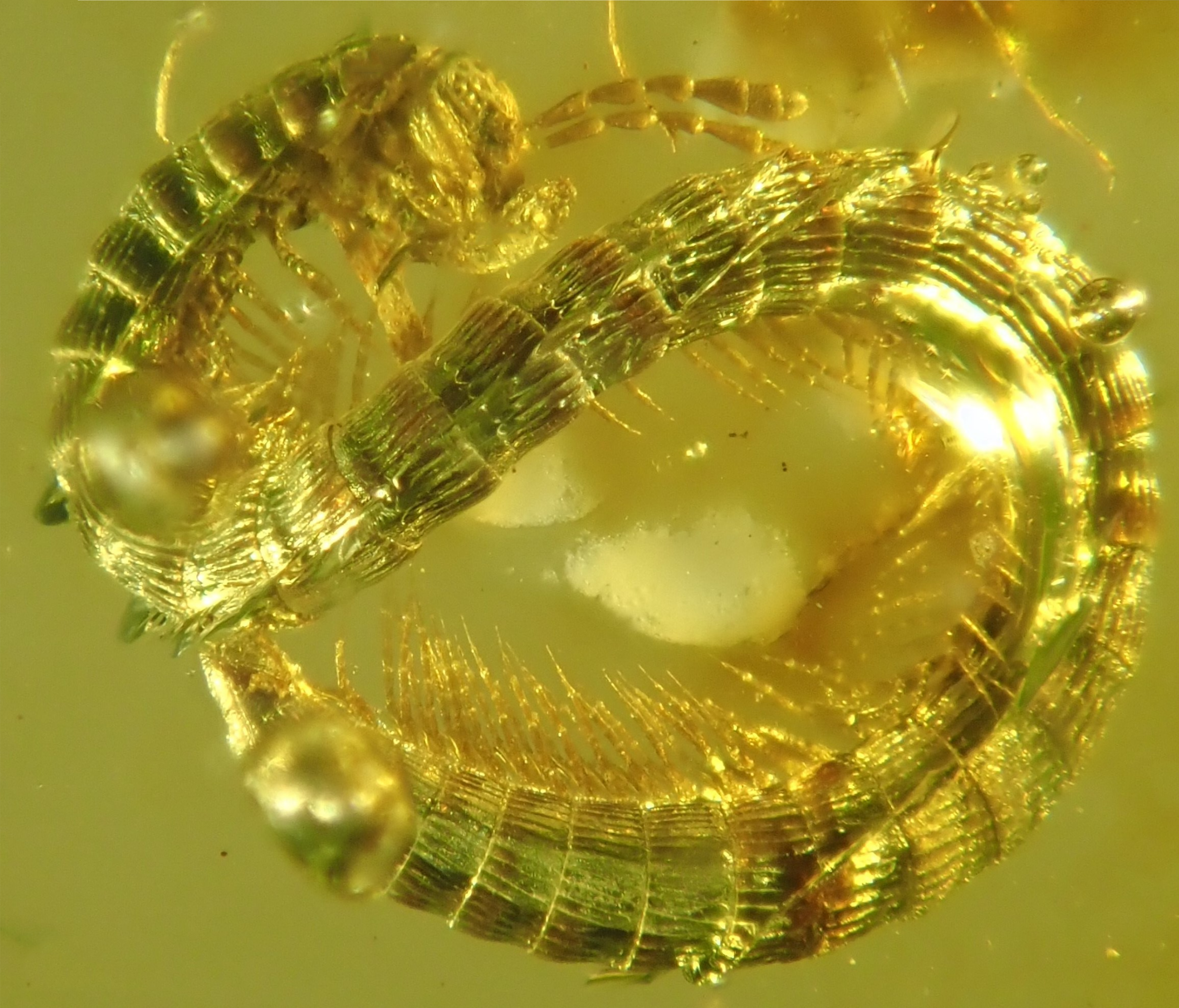

According to a study published in the journal ZooKeys, the creature—which has been named Burmanopetalum inexpectatum—represents the earliest fossil millipede of the animal order Callipodida, casting new light on the evolutionary history of these animals.

"Imagine a tiny millipede of less than a centimeter [0.4 inches]: next to its modern relatives, which measure up to 10 centimeters in length, it would be considered a dwarf!" Pavel Stoev, lead author of the study from National Museum of Natural History in Bulgaria, told Newsweek.

"Even more impressively, it lived in times when terrific dinosaurs and huge arthropods roamed the Earth," he said. "For example, ancient millipedes of the genus Arthropleura that inhabited North America and Scotland some 315 to 299 million years ago are known to have reached 230 centimeters in length. As for Burmanopetalum inexpectatum's habitat, it was most likely a ground-dweller in warm temperate forests of dense pine- and Sequoia-like trees, liverworts and ferns."

The amber containing the specimen was in the hands of Patrick Müller from Germany—who has one of the world's largest collections of animals found amber from Myanmar. In fact, the team was able to examine over 460 amber stones containing millipedes. However, Stoev says that B. inexpectatum—whose name derives from the Latin word for "unexpected"—clearly stuck out.

"As soon as we started to examine the specimen, we came to realize its scientific value, and here's how our project began," he said.

To analyze the specimen and confirm its novelty, the team used an advanced new technology known as 3D X-ray microscopy, which enabled them to reconstruct a digital model of the animal's body and observe tiny traits that are rarely preserved in fossil. The results revealed a number of unusual characteristics: so unusual, in fact, that the scientists had to create a new suborder to classify it.

"Unlike its modern relatives, the species is peculiar in having a specially shaped last segment, which would have played a role in its biology," Stoev said. "Surprisingly, it also lacks characteristic hair-like outgrowths on the back, which are present in all extant members of the order Callipodida. Another unusual feature is its very simple eyes, whereas most of its modern peers have complex vision."

The researchers say that the identification of B. inexpectatum provides new insights into the evolutionary history of its order.

"Being the first fossil member of the millipede order Callipodida ever discovered, we now finally have sound evidence that this lineage emerged at least 99 million years ago," Stoev said. "Furthermore, we now know how the morphology of these millipedes has evolved and which characteristics have undergone the most significant changes."

Leif Moritz, a co-author of the study from the Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, said that millipedes of this order seem to be extremely rare in Burmese amber.

"We looked at more than 460 millipedes trapped in Burmese amber and found only a single specimen belonging to this order," Moritz told Newsweek. "Furthermore, we can say that the basic body plan of the animals has not changed much over the last 99 million years [like] vertebrates and insects, of which several extinct groups are known from that time."

"So far, a great diversity of millipedes has been found in Burmese amber," he added. "In total more than 500 millipede specimens have been reported, which belong to 13 of the 16 today living millipede orders. Among these fossils are the oldest or even first known fossils for several orders. Besides millipedes, there have been many other astonishing animals and plants found in Burmese amber, like several extinct groups of insects or even parts of larger animals like birds or reptiles."

Greg Edgecombe, a leading fossil arthropod expert from the Natural History Museum in London, who was not involved in the research, praised the latest findings.

"The entire Mesozoic Era—a span of 185 million years—has until now only been sampled for a dozen species of millipedes, but new findings from Burmese amber are rapidly changing the picture," he said in a statement. "In the past few years, nearly all of the 16 living orders of millipedes have been identified in this 99-million-year-old amber. The beautiful anatomical data presented by Stoev et al. show that Callipodida now joins the club."

This article was updated to include comments from Leif Moritz.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.