Dreamy and distracted, Meital Guetta struggled through high school in the small town of Shoham, Israel. Her mind wandered to home décor, clothes, dinner plans—anything but schoolwork. "Teachers would say it was a shame, because I was so smart but I wasn't trying," she says. "I was trying."

When she was 23, a neurologist diagnosed her with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, and prescribed Ritalin, a stimulant. It helped, but Guetta didn't like the idea of medicating herself. "I don't want to feel the need to take something every day to be OK," she says. "I just want to be OK."

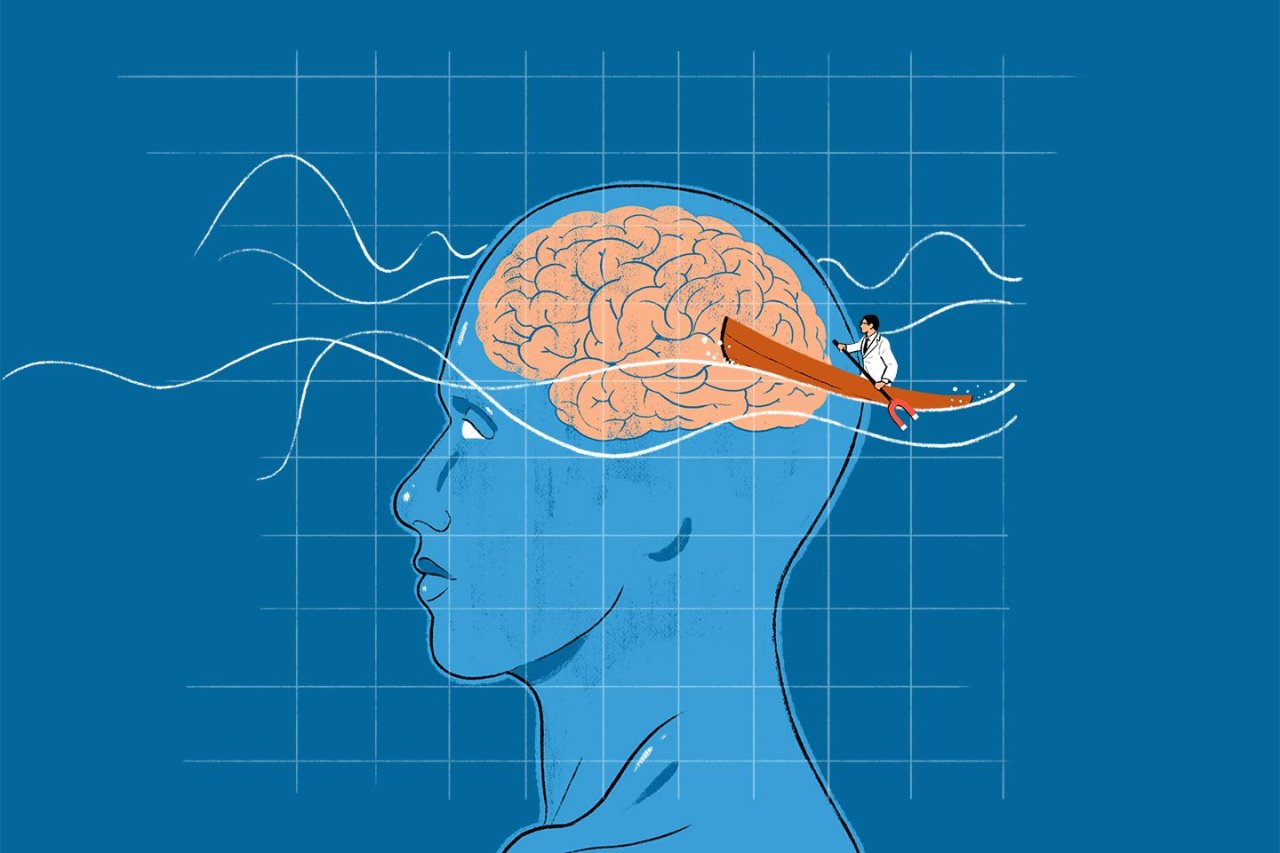

In 2015, she enrolled in a clinical trial at Ben Gurion University. Doctors put a cap with an electromagnetic coil on her head and administered brief, intense magnetic pulses, generating a mild electrical current deep inside her brain. Unlike electroconvulsive therapy, which induces seizures while the patient is under anesthesia, this treatment, known as transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, rarely provokes seizures and is performed while the patient is awake. The treatment was administered to Guetta for half an hour a day, five days a week, for three weeks.

Guetta found the treatment helpful, as did several doctors who have offered the therapy as an alternative to drugs. Besides anecdotal evidence, however, scientists have yet to confirm its effectiveness for treating ADHD in rigorous clinical trials published in peer-reviewed journals. That has put those doctors in an ethical bind: If they've seen positive results, should they still wait possibly years for studies to come out and regulators to weigh in, or keep offering treatment they believe can be helpful?

The question is relevant to the roughly 6 million children and 10 million adults in the U.S. who have ADHD. At least 15 percent of these people reportedly either don't benefit from standard medications—mostly stimulants like Ritalin—or can't tolerate the side effects, which can include insomnia, anxiety, loss of appetite, cardiovascular risks and stunted growth. Others, like Guetta, simply don't want to take drugs.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved TMS in 2007 for patients with depression who didn't respond to medication. But for ADHD, "there isn't any evidence to my knowledge showing that it's clinically effective," says Joel Voss, an associate professor of neurology at Northwestern University. Treatments for ADHD outside clinical trials "would be unethical," he says, "especially when they are so expensive."

Daily half-hour treatments can run for five weeks or more and cost as much as $16,000 total, doctors told Newsweek; without FDA approval, insurance companies will not cover TMS as an off-label ADHD treatment. Doctors who want to help their sometimes-desperate patients have to evaluate data that hasn't received the medical profession's stamp of approval. Earlier this year, Brainsway, the Israeli company that developed Guetta's treatment, released results of a clinical trial of 53 adult ADHD patients who reportedly experienced "significant" benefits. But these results are difficult to evaluate because they have yet to be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

Rustin Berlow, a psychiatrist at the American Brain Stimulation Clinic in Del Mar, California, is one of the doctors justifying their use of TMS based on anecdotal evidence. He says patients he was treating for depression reported that TMS helped them focus. He has since treated about 100 people with ADHD, the majority of whom, he says, have shown some improvement. Another doctor, who preferred to remain anonymous, tells Newsweek he considered himself a "shaman" as he experimented with TMS on some 30 patients over several years. Eventually, he settled on stimulating brain regions involved in executive functioning—including impulse control and working memory—while patients engaged in "brain gym" exercises on a computer.

"I didn't have the data to support what I was doing," he says. "But I had the opportunity of working at a boutique clinic where lots of people paid for services out of pocket. There were many desperate patients, and I argued that if we had the ability to do it, and we know it's safe, why wouldn't we go ahead with it and learn as we go?"

Most patients responded to the treatment, he says, even as colleagues "mocked" him for his faith in the therapy. He eventually stopped administering TMS for ADHD.

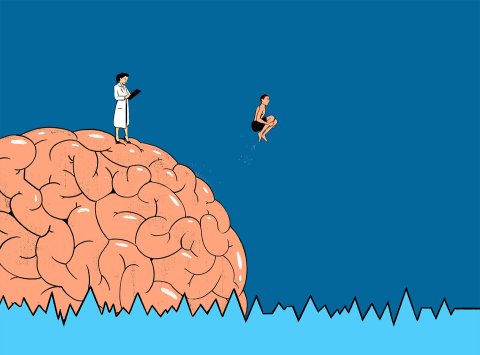

Voss and other experts think the experimental approach is too risky to justify. Better functioning of one area of the brain may come at the detriment of other capacities, they note—a particular concern for young patients, whose brains are still developing.

"Please, Lord, don't do this stuff to children!" Voss wrote in an email. "At least not without a tremendously compelling neurological rationale and an impenetrable mound of data to show that you'll at least do no harm."

TMS is not pain-free, and researchers note it can entail a small chance of seizures. Guetta described her sessions as comparable to being "hit on my head with a hammer." But she kept coming back. "It was absolutely amazing," she says. "I felt like a better person, like I could take classes and listen, like, wow, maybe I'm not lazy after all." For Guetta, at least, the risk seems to have paid off.