Work on New York City's Second Avenue subway began in 1972. After decades of false starts, the first phase was opened to the public in January 2017. It runs about 2 miles.

Compare that to Switzerland's Gotthard Base Tunnel, the earth's longest at 35.47 miles (roughly three times the length of Manhattan), which opened in 2016. That required the Swiss to drill a hole through the Alps; it is, in parts, one and a half times deeper than the Grand Canyon. In all, the tunnel took 14 years of round-the-clock work. "When you're the world's biggest laundering device, it's easy to get things done quickly," says Tom Sachs.

The American conceptual artist has long been fascinated by the efficient Swiss, including references to the country in work as far back as the early 1990s. His first visit, at 16 or 17, was on a ski trip. "Even at that age I was so impressed by the precision and cleanliness of the place, the vast expanses of natural beauty," says Sachs. "But there's an illusion going on there. Nature is a wild, violent place where death and chaos rule. In Switzerland, it's been mitigated by man—manicured and cultivated." And while nature is obviously revered, "this is also a country that has devoted incredible resources to particle physics"—a science, he adds, that has a finite risk of causing global destruction.

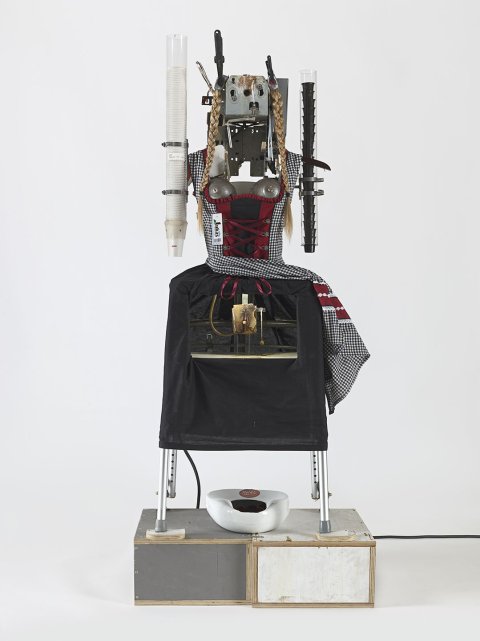

Over three decades, Sachs's art has been devoted to his "desire to remake the world not as it is but the way it ought to be." Through his signature technique of bricolage, he repurposes collected materials into objects that populate elaborate and wittily inaccurate alternative universes—crafty comments on consumerism, violence, cultural icons and societal systems. His NASA-tweaking "Space Program: Mars," for example, filled New York's Park Avenue Armory in 2012 and required (and achieved) an extraordinary suspension of disbelief; the show had viewers rooting for astronauts traveling in plywood capsules operated with Atari joysticks.

In his new show, "The Pack," at the Vito Schnabel Gallery in the Swiss town of St. Moritz, Sachs takes on Switzerland as an idealized brand, pointing up the inconsistencies in the country's self-image, including its wholesome archetype, Heidi, from Johanna Spyri's 1881 novel. Is it the globe's largest bank, birthplace of the Red Cross, a neutral political and humanitarian model, and an archetype of perfection? Or is it a corrupt, self-centered power that implies more generosity than it delivers?

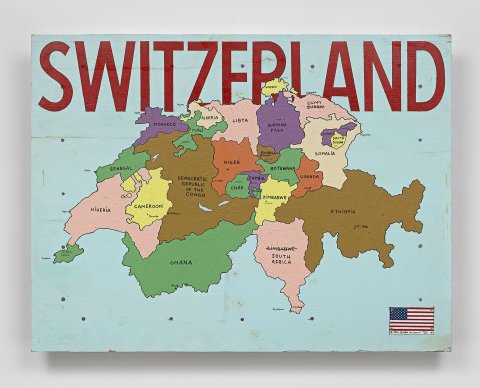

"I want to make it clear: This isn't about bashing Switzerland, it's about understanding all sides of it at once," says Sachs. But the work within the show is clearly spoofing the folly of perceived utopias, particularly in a world riven by poverty and injustice. In the painting Switzerland, for example, the 26 cantons of the Swiss Confederation are renamed for Africa's sovereign states. What, the piece slyly suggests, might the enormous resources of Zug (Switzerland's wealthiest canton) do for a devastated country like Burundi?

"Careful planning and unlimited funds versus bricolage and doing what it takes to get by, which is the struggle of every African country, without exception," says Sachs. "It's about the most organized and least soulful place versus the least organized and most soulful place. Certainly from a cultural standpoint, Africa has always been a global generator of everything meaningful in art."

The show and central work take their title from a seminal 1969 installation by German artist Joseph Beuys that had 24 wooden sleds emerging from the back of a VW bus, each equipped with supplies for primitive survival in an emergency. Sachs's Pack swaps the sleds for three working electric motorcycles. When activated in a ritual joy ride, they symbolize the Pontifical Swiss Guard, one of the world's oldest intact military units and the Vatican's army since 1506.

"Those are the guys who wear those ridiculous purple and yellow outfits that Michelangelo supposedly designed," says Sachs. "But they are no joke—they're Switzerland's Navy SEALs. They might carry halberds and swords, but they've got Glocks underneath."

A final irony for a country espousing neutrality. Then again, says Sachs, "I kind of admire that. If we're going to have police, we want the best—no bad apples here. This isn't people being pulled over for driving while black in America."

"The Pack" will be at the Vito Schnabel Gallery in St. Moritz from December 28 through February 3.