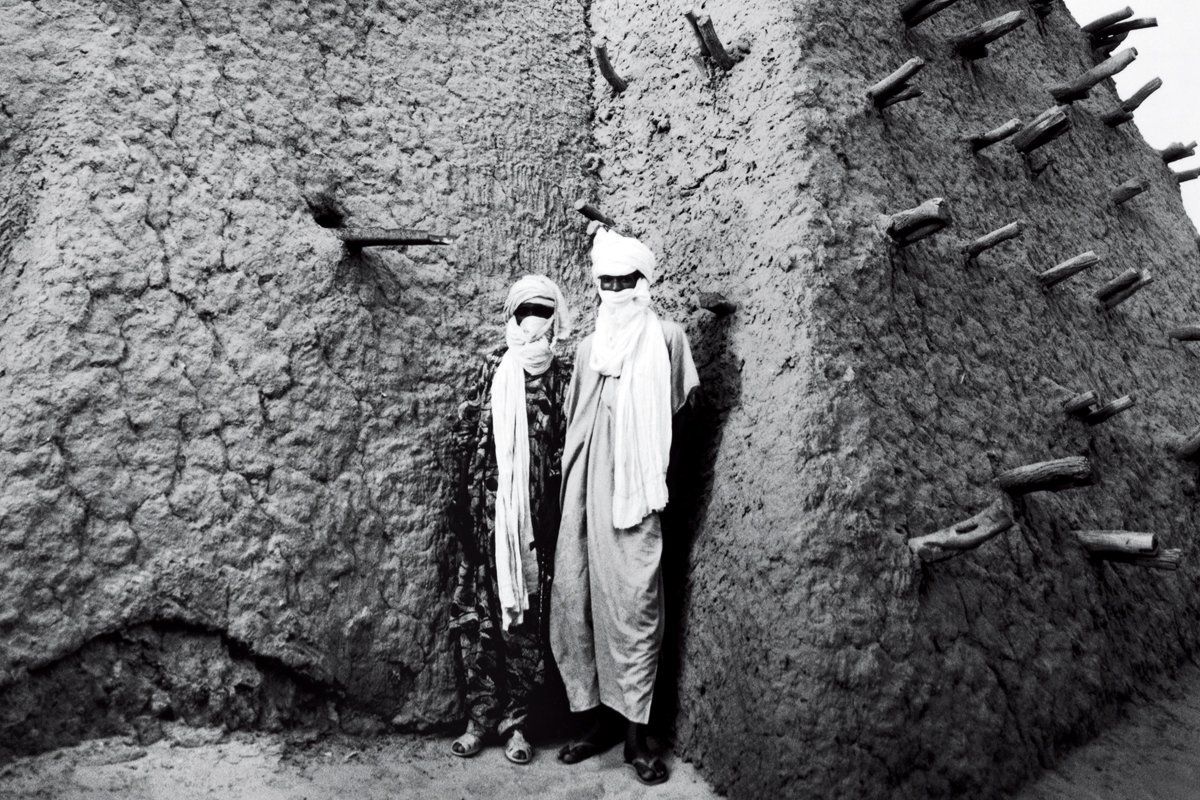

When it comes to distant destinations, no name is quite so evocative, so utterly haunting, as Timbuktu. Used by us all to connote a far-flung spot off all the maps, it's somewhere that a great deal of Americans don't realize actually exists. Or, rather, they didn't realize it existed until earlier this year, when the region where the city lies began to spiral dangerously out of control.

Lost in the desiccated Saharan sands of northern Mali, Timbuktu has found itself front-page news, and for all the wrong reasons. In scenes straight out of Taliban-held Afghanistan, an ultra-hardline form of Islam began sweeping through the region this April, as a radical Tuareg-led militia seized control. Calling themselves the Ansar Eddine, literally the Defenders of the Faith, they are intent on imposing a draconian Taliban-style interpretation of Islam. And, as with the Afghan Taliban, they are once again backed by al Qaeda, for whom the region represents an important new western front.

The militia regime comes less than six months after a failed coup d'état in the Malian capital, Bamako, in which the nation's president, Amadou Toumani Touré, was deposed by his own soldiers. Incensed at the militia's gains in the north of the country, the rebellion led to a power vacuum that further strengthened the Tuareg hand.

For decades, the Tuareg have yearned for their own northern state and a complete separation from the government based at far-off Bamako. A realm of parched desert, one that's intensely poor, northern Mali covers an area about the size of Spain. There was never a real hope of gaining full independence, not until this year—the tipping point arriving as a byproduct of the Arab Spring.

The change for Mali's northern region, and for the ancient city of Timbuktu, began last year across an ocean of sand, in Libya. After becoming an outcast in the Arab world and beyond, that nation's late leader, Col. Muammar Gaddafi, played the African card. Having seduced the continent's dictators, a clutch of them proclaimed him as Africa's "king of kings." Gaddafi recruited scores of Tuaregs into his army from across the Sahel, including from Mali. He trained them, armed them to the teeth, and employed them in his conflicts in Chad and elsewhere.

All was well in Mali until Gaddafi's ignominious demise. Then, heavily armed, different factions of Malian fighters seeped back south toward their homeland. War-ready and battle-hardened, they took with them small arms, antiaircraft missiles, and everything in between.

With the shock waves of the Arab Spring traveling across the Sahara, the upheaval has spelled catastrophe for the fragile outpost of Timbuktu. As much as half of the city's populace has fled. Some have sought refuge in neighboring countries, such as Mauritania and Burkina Faso. Those without the means to escape fled into the desert and hid. Unable to venture into the area, journalists and aid organizations, like Amnesty International, have to watch from the sidelines as the situation becomes more critical by the day.

In the searing summer heat, and against a stifling climate of fear, the Ansar Eddine is ratcheting up the pressure. In late July the group gave the order for the city's centuries-old Sufi mausoleums to be leveled, declaring them to be at odds with their own hardline blend of Islamic faith.

A UNESCO World Heritage site, Timbuktu has for centuries been associated with Sufis, a mystical and spiritual fraternity, themselves closely connected with Islam. More than 200 Sufi saints are buried in free-standing mausoleums and within the compounds of mosques, tombs that have become the latest target of the Defenders of the Faith.

Regarding them as idolatrous, the Islamist militia has taken hammers and shovels to their baked-mud adobe walls. They even destroyed a pair of ancient tombs set in the compound of the city's celebrated Djingareyber mosque.

For all intents and purposes Timbuktu has been sealed off from the outside world just as it was through history. No foreign journalists are permitted anywhere near the city, and all Western aid workers have long since been evacuated.

Speaking from Bamako, one newly arrived refugee there, named Lassana, recounted his last afternoon before fleeing with his family: "A pickup truck arrived at a mausoleum near my home," he said. "In the back were five or six young men with guns. They were laughing and jeering, waving their weapons in the air. I told my wife and children to stay inside and to make no noise. Then I went out and watched as they broke down the shrine, whooping as they did so.

"Before they left, they beat one of my neighbors, an old woman, because they said her veil wasn't covering all of her hair. It was at that moment I realized we had to escape, because time had stopped in Timbuktu."

Another refugee, Mohamed, last week reached London, where I met him. Dressed in the flowing pale blue robes of the Sahara, he asked for his identity to be concealed for fear that his family, which is taking refuge to the south in Burkina Faso, would be sought out and harmed.

"Timbuktu is like a cemetery now," he told me, his eyes glazing over with tears. "You wouldn't recognize it. Anyone who knew it before would weep. So many people have left. There's very little food at all and hardly any fuel or water. Ordinary people are being harassed and whipped, and the Sharia law being practiced is extreme. The people of Timbuktu have always been easygoing and have never known this kind of oppression. We need to tell the world what's happening, but who will listen to our cries?"

As I learned, the only way to fully understand the distinctive tragedy of what's happening in Timbuktu now is by slipping back in time and by examining the city's role and culture to generations past. And, oh, how things have changed.

Situated nine miles north of the Niger River's flood plain and on the southern edge of the Sahara, Timbuktu had for many years been an exotic destination on the jet-set tourist trail. Visitors would fly in and out, often in a single day, once their passports had been stamped and they had been photographed beside the towering adobe mosques and madrassas for which Timbuktu is so famed.

The tourists brought money, and the money brought security and comparative wealth to the souvenir sellers, the guides, and the owners of a few modest hotels. Not bad for a place trading purely on its name.

After traipsing past the great adobe structures, which look strangely futuristic, tourists were cajoled to shell out plenty of cold, hard cash for Tuareg knickknacks. And after that, if they weren't totally parched by the heat, they would be taken on a tour of houses where, supposedly, the first Christian explorers had stayed—most of them heavily in disguise.

The best known is a rather new-looking house where the indefatigable German explorer Heinrich Barth sought refuge during his stay in Timbuktu in 1853. Another, equally pristine and rebuilt, was where French explorer René Caillié is said to have put up during his two-week sojourn in Timbuktu, in 1828. Fortunately for the Frenchman, an English explorer named Alexander Gordon Laing, who reached the legendary city two years before him, was slain en route home, allowing Caillié to claim a 10,000-franc prize for being the first Christian to reach Timbuktu and live to tell the tale.

Generations of European explorers had set out to locate, and then to sack, far-off Timbuktu. Most of them never returned alive. They perished in the infinite and unrelenting dunes of the Sahara, long before they ever got close to the city they believed to be an African El Dorado.

That the irresistible texture of the name drew adventurers toward it through history is something for which we must be thankful. Were it not for the enduring preoccupation with the legend of Timbuktu, the current events there would be regarded as merely another forgotten skirmish in deepest, darkest Africa.

The myth of a city crafted from gold came about from a mixture of exaggeration and good publicity. The seed of the legend seems to have been sown by the caravan of Sultan Mansa Musa, ruler of the Mali Empire. In the first quarter of the 14th century the magnificent cortege made its way eastward to Mecca on the Muslim pilgrimage. Jaw-dropping by any standards, it was said to have contained as many as 60,000 people—among them soldiers, courtiers, and servants. The grand procession boasted 15,000 camels, each one laden with perfume and sumptuous foods, with ivory and gold.

It's clear that a great many of the early accounts of the "golden city" were actually penned by people who had never experienced the place firsthand. In 1620 an English explorer in West Africa named Richard Jobson was informed that Timbuktu was abundant in gold. He wrote: "The roofs of its houses were represented to be covered with plates of gold, the bottoms of the rivers to glisten with the precious metal, and the mountains had only to be excavated to yield a profusion of metallic treasure."

While there is no doubt that Timbuktu was an important center, and one connected by the pilgrimage routes to Mecca, it is unlikely that it was ever an African El Dorado. Instead, it was primarily known for its trade in salt—cut by hand in great blocks from an ancient dried salt lake at Taoudenni, deep in the Sahara—and its learning.

In the 16th century, the golden age of Timbuktu, the city was one of the most important centers of Islamic scholarship anywhere on earth. There were well over 100 madrassas, where students mastered the Quran and Islamic jurisprudence, and the sciences as well. In the secluded retreat of the desert, scholars devoted their lives to study and to committing their knowledge to paper. The libraries they created from centuries of learning were the real treasure of Timbuktu.

The extremely dry conditions have ensured the preservation of a great many ancient manuscripts. Some estimates put the total number at as many as 700,000. Many thousands were buried in times of conflict and uncertainty, only to be excavated in the relative security of recent times. Until this year's conflict, work continued at several centers in Timbuktu, to scan, archive, and study as many of the documents as possible.

There is no accurate information on whether the Ansar Eddine has yet begun to destroy this precious resource. But there are reports of the libraries and the research centers being pillaged, their contents sold on a thriving black market.

Thomas Fessy, the BBC's correspondent in West Africa, sees the future for the region as grim. "Until the political imbroglio is solved in Bamako, no decision will be made regarding the north," he says. "West African states are thinking about military intervention, but this isn't bound to happen any time soon. Mali is a destination tagged as a red zone by all Western governments to their nationals. Several people are still held hostage in the region. So I think in the short and mid-term, it is very hard to see anything but a picture that will grow darker and darker."

The result: northern Mali is being plunged back in time. At its core is Timbuktu, an ancient city that's bearing the brunt of grinding social devastation. Intent on achieving its own form of Year Zero, the militia announced that it will enforce the stoning of adulterers, as well as the punitive mutilation of thieves and the veiling of all women.

And that's just the start. The city's historic monuments and shrines are being leveled, its cultural heritage being ripped to pieces, all this as the traumatized population flees.

There's not enough in the way of food, water, or basic medicine, and most vestiges of modern society are being targeted. Soccer, recorded popular music, television, and even videogames have been on the militia's hit list, too. Men and women who are unmarried or unrelated are forbidden to walk down a street together or even to sit beside each other on a bus.

Eager to instill fear as a way of exacting the letter of the law, the leaders of the Ansar Eddine are making an example of anyone who dares to disobey them. In one atrocity in recent days, an unmarried couple in the northern town of Aguelhok were stoned to death for infidelity, having first been buried up to their necks in sand. With a large crowd watching and armed with Kalashnikovs, the Islamist militia hurled stones at the pair until they were dead—a stark warning to everyone present that Islamic Sharia will be enforced at all costs.

Of the murder, Paule Rigaud, Amnesty International's deputy director for Africa, said: "This killing is yet another human-rights abuse committed by the combatants who control the north of Mali, and illustrates the climate of fear that armed opposition groups have created within the areas they control."

In the wake of the stoning came the first public amputation for theft at the small town of Ansongo. The accused man had his hand held down on a makeshift block. Then, with a crowd of onlookers in an arc around him, the militia's self-appointed law enforcer cleaved it off with a sword, before holding it up as a grim trophy, exclaiming, "Allahu akbar!" ("God is great!")

A year and more since the Arab Spring began, Timbuktu and its surrounding region have become the latest realm to be plunged beneath the veil of darkness. One can only hope that this latest, bleakest era in the history of Africa's most elusive destination will soon pass, opening the way for it to join the more promising future emerging elsewhere in the Islamic world.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.