This article first appeared on the London School of Economics site.

For years, the Republican front-runner and New York billionaire Donald Trump has actively investigated, propagated or defended many conspiracy theories. He is perhaps the most publicly conspiratorial presidential contender in recent U.S. history.

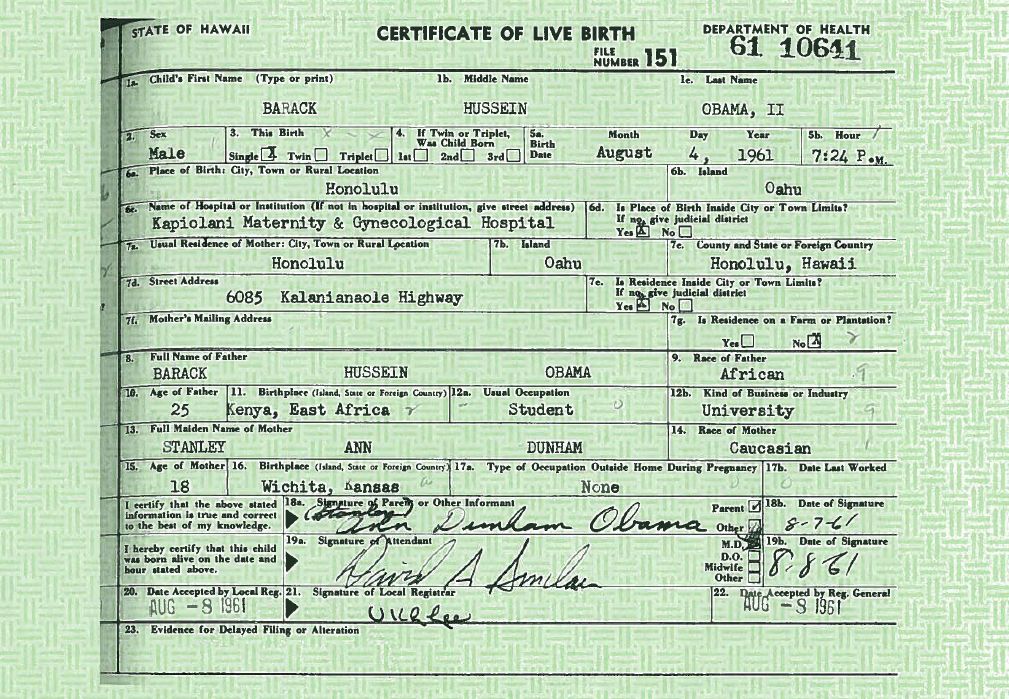

Trump's foray into the conspiratorial began with birtherism, the idea that President Barack Obama was born outside of the United States. When Trump's investigation failed to provide evidence of a foreign birth, he moved on to suggest conspiracies about Obama's college transcripts and more recently the 9/11 attacks. He is also dancing around the government's role in potentially covering for accomplices in the San Bernardino, California, shootings.

Given the current electoral landscape, there is a significant possibility that Donald Trump will become the next president of the United States. With his tendency to publicly endorse or condone conspiracy theories, how might he lead the country?

Conspiracy theories scapegoat a group and accuse them of committing evil acts. When this powerful rhetorical device is used by the state against the vulnerable, they become dangerous because the scapegoating is now backed by the threat or use of force.

If we look outside the U.S., Hitler, Stalin and Mao propagated conspiracy theories targeting vulnerable domestic groups. This led to the deaths of millions. The current Castro and Kim Jong-un regimes in Cuba and North Korea, respectively, use conspiratorial rhetoric to maintain control.

It goes without saying that the political arrangements in World War II–era Germany, Russia and China and contemporary Cuba and North Korea are very different than those in the U.S., but what they do suggest is that consolidated power and conspiracy thinking don't mix well, particularly when the leaders are the ones levying the charges of conspiracy.

We have witnessed smaller-scale incidents in U.S. history. Even before independence from England, innocent women were tortured and murdered because local governments thought they had conspired with Satan.

In the 1950s, the House Un-American Activities Committee pitted the full power of Congress against Hollywood actors and writers. Many laws were passed during the Red Scare violating the rights of millions.

Conspiracy theories about Japanese-Americans during World War II led to internment camps. These incidents are telling of what can happen when the powerful use conspiracy theories to target the vulnerable.

Conspiracy theories have been long intertwined in our politics. Since the Revolution, Americans have been alerted to conspiracies by the Illuminati, Freemasons, Catholics, monopoly trusts, Communists and many, many others.

Conspiracy theories are not confined to a pathological fringe: Polls suggest that all Americans believe in at least one, and many believe in several. Despite their generally bad reputation, conspiracy theories can alert people to coming dangers, encourage good behavior by the powerful and hold leaders accountable for wrongdoing.

In this context, conspiracy theories can be a net positive: Just consider the two cheeky journalists at The Washington Post who followed a conspiracy theory to bring down a corrupt president.

But such benefits are not sometimes without grave costs. Conspiracy theorists act on dubious information, engage in scapegoating and, worse, have attempted and committed murder.

Take Timothy McVeigh, for example—he believed the government was plotting to take away rights, so he conspired against the government by killing 168 and injuring more than 600.

Or examine the events at Ruby Ridge. Government agents believed that groups in the northwest were conspiring, among other things, to overthrow the government, so they conspired to infiltrate and subdue these groups. These groups, ironically, believed that the government was conspiring against them. This toxic mix ended with the U.S. government paying out $3.1 million for killing Randy Weaver's wife and son and then conspiring to cover up the circumstances of those deaths.

These two cases are extreme and unusual; the vast majority of people who believe in conspiracy theories do not commit either violence or conspiracy-inspired violence. But when such cases do arise, they are of little surprise to social scientists, who find that those who are the most drawn to conspiracy thinking are also the most accepting of violence and the most willing to conspire themselves to reach their ends.

But now imagine if we were to put a conspiracy theorist into the presidency, sitting at the most powerful desk in the world, complete with the codes to a nuclear arsenal and control over a military apparatus more powerful than any other.

In the U.S., conspiracy theories resonate most when they originate from the least powerful and accuse the most powerful. Those without power use conspiracy theories to close ranks, stay alert, point out potential dangers and call for action against a more powerful opponent. In modern party politics, this has usually taken the form of the out-of-power party accusing the in-power party of conspiring.

For example, as President George W. Bush left office, the public became less interested in theories that pinned 9/11 conspiracies on him and instead became fascinated by the new president's birth certificate.

Using a time series of 120,000 letters to the editor of major newspapers, we have shown that this pattern goes back at least to the 1890s. After reading these letters and picking out the ones that espouse a conspiracy theory, we found that during the years a Republican is in the White House, conspiracy theories about the right occupy about 16 percent of our conspiracy theory letters each year, but they decrease to 5 percent when a Democrat is in the White House.

Conspiracy theories about the left occupy about 6 percent of our yearly sample during Republican administrations, but increase to 15 percent during Democratic ones. This trend is the same for both elite and nonelite letter writers. Who controls the White House invites conspiracy theories to themselves and their party.

While this pattern has led to overheated rhetoric and occasional gridlock, the effects are usually benign because the accused are usually powerful and well protected. When powerful actors attempt to use conspiracy theories to attack the less powerful, those conspiracy theories generally fail to resonate because Americans view them as unseemly; we don't like to see the weak be attacked by the strong with conspiracy theories.

For example, President Bill Clinton received little sympathy when his wife blamed their troubles on a "vast right-wing conspiracy." That this conspiracy theory became a punch line is a good thing; we would not have wanted the president to rally public support for hunting down and bringing to justice those supposed "right-wing conspirators."

This is one reason why having a conspiracy theorist in the White House becomes dangerous. Should the president be able to rally support around a conspiracy theory, it could lead to the violation of rights on a massive scale.

Many of Trump's more popular conspiracy theories accuse powerful, well-protected actors of engaging in conspiracies (e.g., Barack Obama). Trump's conspiracy theorizing becomes more dangerous when he bucks usual trends and turns his attention away from the powerful and to the more vulnerable.

He has suggested that Mexican immigrants are murderers, rapists and drug dealers, and that they are part of a plot by the Mexican government. He has suggested that Syrian refugees and Muslims more generally are secret terrorists of the Islamic State militant group (ISIS), and that there are giant networks of Muslim-Americans who aided, abetted and continue to cover up attacks.

On top of his conspiracy theories, Trump's rhetoric blames foreigners and immigrants for taking our jobs and our money, usually with allusions to violence: "They're killing us!"

Trump may or may not believe his own rhetoric; it's hard to know. If he truly does have a conspiratorial mindset, then his actions—if he were to become president—would be partly driven by his dubious beliefs.

Richard Nixon's time in office provides a preview. Nixon believed that journalists, Jews, Democrats and intellectuals were conspiring against him. So he used the power of the federal government to conspire against them. Recent admissions about the origins of this country's drug war claim that it was part of Nixon's plot to go after anti-war protesters and blacks.

But even if Trump's conspiracy theorizing is merely an act, he has shown not just that he knows how, but also that he is very willing to use, conspiratorial rhetoric to rally (sometimes violent) support. Note that whether Trump believes this or not, many of his supporters do, and his past rhetoric will entrap him, bending his behavior toward their expectations.

Conspiracy theorists are often tactically brilliant in climbing the greasy pole to leadership, but they're often strategically daft when they get to the top. It's hard to sustain fear for extended periods of time, and it's hard to maintain credibility or craft effective policy when relying on conspiratorial arguments. (See, for example, Venezuela.)

Stalin's paranoid purges almost cost him his state (Nazi Germany attacked after he had destroyed much of his officer corps); Hitler's obsession with Untermenschen conjured up an unwinnable war Germany couldn't escape; Nixon's dirty tricks booted him from office in disgrace.

Should Trump become president, his current conspiracy-driven policy views could either force him to act or leave him with the consequence of his followers acting where he does not.

Joseph E. Uscinski is an associate professor of political science at the University of Miami's College of Arts and Sciences and the co-author of American Conspiracy Theories with Joseph M. Parent.

This article gives the views of the author and not the position of USAPP–American Politics and Policy nor the London School of Economics.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.