Donald Trump is doing something that Democrats have never been inclined to do: go after George W. Bush on the subject of 9/11, accusing him of a lack of vigilance.

A back-and-forth spat between the two archenemies in the Republican primary, Trump and Jeb Bush, lasted all of last weekend, after the Bush campaign published an ad attacking Trump for having poor judgment.

Trump responded on Friday by telling Bloomberg, "When you talk about George Bush, I mean, say what you want, the World Trade Center came down during his time."

President Bush's former White House press secretary, Ari Fleischer, retaliated on CNN, saying that "when Donald Trump implies that since 9/11 took place on Bush's watch he is partially responsible for it, he's starting to sound like a truther," referring to the conspiracy theorists who believe 9/11 was an inside job by the U.S. government. Trump, of course, wasn't saying that Bush dynamited the Twin Towers, as some conspiracists have ranted. He is charging that because the towers were attacked while Bush was in office, America was "not safe" during his presidency.

On Monday morning, Trump wasn't ready to end the feud, unleashing a tirade in a string of tweets.

"@rdpaga: @JebBush we were attacked on ur brothers watch. That's not safe. I have respect 4 GW but truth is no WMD in Iraq & 911

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 18, 2015

Jeb is fighting to defend a catastrophic event. I am fighting to make sure it doesn't happen again.Jeb is too soft-we need tougher & sharper

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 19, 2015

Jeb Bush, who has opted to campaign as just "Jeb!" and doesn't use his last name in advertising (the exclamation point "connotes excitement," he told Stephen Colbert), clearly doesn't want to answer questions about his brother. He has mostly failed to differentiate himself from George ideologically because there are very few discernible differences (just look at how he responded to Colbert's question on the subject).

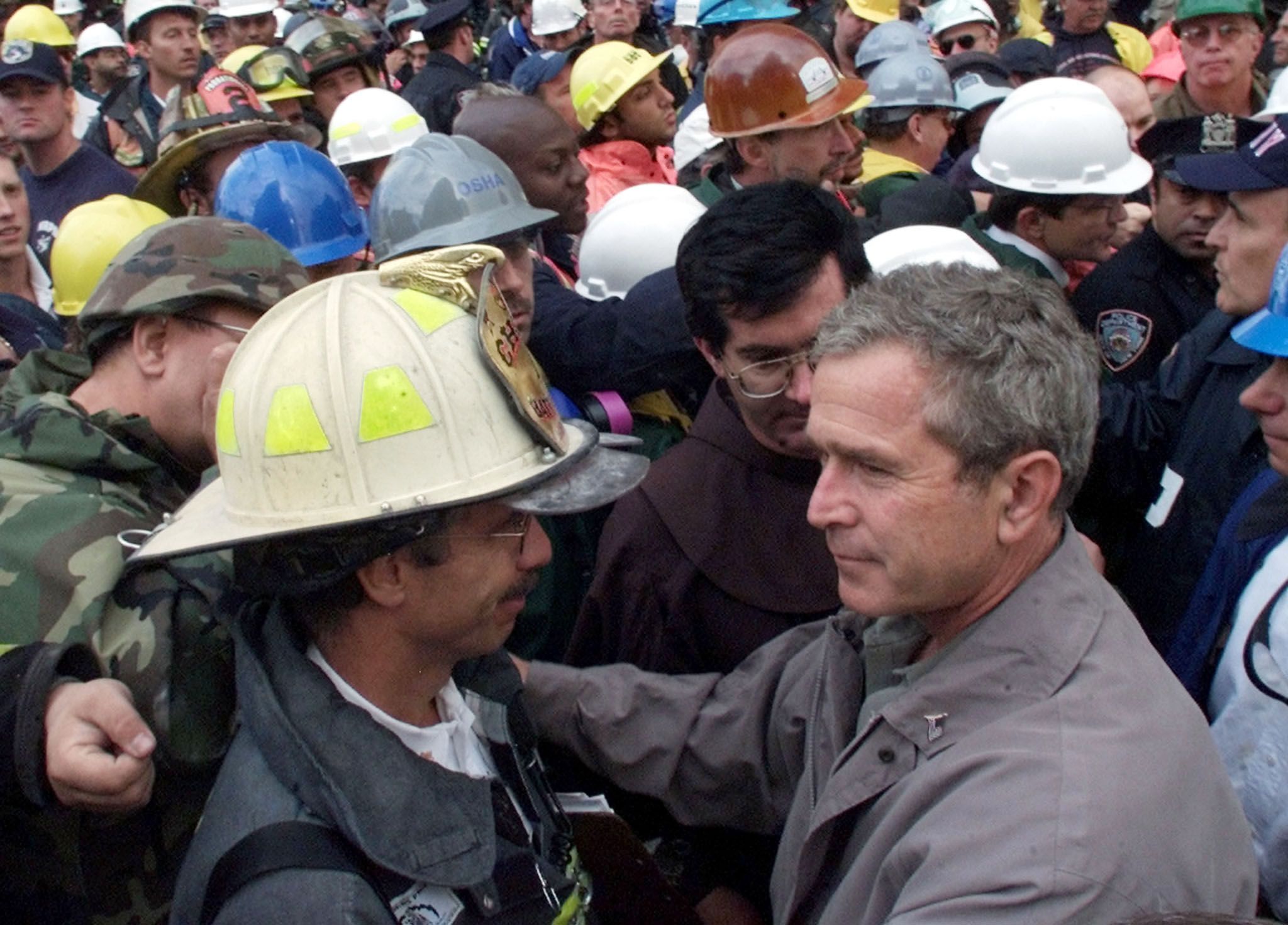

Despite other criticisms of George, his response to 9/11 is supposed to be one area where the 43rd president shined. Forget the approval ratings spike he enjoyed after the attacks. Forget the first pitch at Yankee Stadium. Forget the speech at Ground Zero where he put his arm around a firefighter and told the assembled crowd that "the people who knocked down these buildings will hear from all of us."

Until now, no nationally known figure has pointed to why he was standing on the rubble in the first place.

Nobody in politics wants to ask how much responsibility George Bush shoulders for the attacks, because the widely accepted narrative is that he couldn't have done anything. Even former Democratic National Committee Chairman Howard Dean told MSNBC on Monday morning that it would be ridiculous to blame the president, saying that anyone who takes such a position is wading into dangerous political territory. American politicians have tended to treat the 9/11 attack as immaculately conceived.

That it took the brash Trump to plunge into this turf says a lot about how the country continues to wrestle with this tragedy. The truth is that the question of responsibility has already been addressed in a we're-all-to-blame sense. The 9/11 Commission report, which the Bush administration initially opposed, tells a sobering story about American vigilance prior to the attacks.

In the closing months of the Clinton administration, Richard Clarke, the head of the National Security Council's counterterrorism efforts, prepared an Al-Qaeda policy analysis that he presented to the incoming Bush administration. According to the 9/11 Commission, Clarke found that Bush's national security and foreign policy team "had a steep learning curve" to overcome when it came to transnational terrorism. The team had largely been carried over from eight years before, when many of them had served in the administration of George H.W. Bush. Partially as a result of this, they were more focused on the threats posed by aggressive states like North Korea. National security officials didn't hold a Principals Committee meeting on Al-Qaeda until September 4, 2001.

Clarke's continual urging of administration officials to take a closer look at Al-Qaeda didn't absolve the Clinton administration of blame. He criticized U.S. foreign policy "past and present" and told the new leaders to imagine a future in which hundreds of Americans were killed by terrorists at home and abroad. The bombing of the USS Cole in 2000 had raised awareness about potential attacks on military targets, but Bill Clinton's efforts to capture bin Laden had failed, his rocket strikes against Al-Qaeda bases didn't hit the terrorist leader, and he did not pursue a declaration of war from Congress. Military retaliation against Al-Qaeda bases, something that Clarke agitated for, hadn't materialized. Perhaps the state of things should not come as a surprise: In the 2000 presidential campaign, George had run a campaign based on domestic issues and character. The neocon foreign policy advisers he inherited from his father were thinking about Iraq's Saddam Hussein.

There's no indication from the 9/11 Commission that U.S. intelligence had a lack of information in the months leading up to the attacks, only that there was a failure to "connect the dots." Terrorist threat advisories that summer warned of impending "spectacular" terrorist attacks. Condoleezza Rice, then the national security adviser, suspected that a car bomb would be the weapon of choice. Clarke wrote desperately to Rice on several occasions, saying that the Al-Qaeda network was lighting up with communications anticipating an attack. On August 6, George was briefed on bin Laden's determination to strike inside the U.S., as Newsweek's Kurt Eichenwald reported for The New York Times in 2012. The government was monitoring sleeper cells in the U.S. and terrorist networks abroad, but it was not anticipating an attack from foreigners who had infiltrated the U.S.

Meanwhile, domestic agencies like the FBI were in disarray. The 9/11 Commission report paints a picture of a counterterrorism bureaucracy hampered by a lack of leadership and unprepared to mount an effective response to the increasing threats. The report identifies "at least two mistakes" made by Al-Qaeda operatives that could have been tip-offs.

Somewhere amid all the communications, information and actors, there was a fundamental disconnect between the story being told by the intelligence community and the prevalent mindset that the U.S., the world's only remaining superpower, could not be hit at home.

For the rest of the Bush presidency after 9/11, the average American walking through an airport would hear PSA announcements declaring that the national aviation "threat level" was at orange—a perpetual danger signal that defined a politics of fear. The color orange came to represent the conviction held by conservatives that preventing another 9/11 justified everything from the Patriot Act to enhanced interrogation to pre-emptive military action.

But in the weeks before 9/11, the threat was there, and no announcements were made.

Trump's attacks on Jeb's brother essentially postulate that the world was not safe during the first year of his presidency. The official record bears out that narrative, although whether the Bush administration could have identified the hijackers and broken up the plot is still a difficult question.

The second part of Trump's attack has to do with Bush himself—did the president fail to adequately respond to the security threats or was the chain of command as a whole to blame? Just because something happened "on your watch," is it your fault? The answer to that is even more complicated.

The war on terror would initially turn to Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan, but the attacks also became a rationale for the war in Iraq, where failed intelligence about weapons of mass destruction made it look as if the administration was firing with a blindfold. That response, if not the events of 9/11, fell squarely onto Bush's shoulders.

That's where politics come in. The Democrats of 2004, including eventual presidential nominee John Kerry, campaigned on criticizing Bush's decision to invade Iraq. In the debates, Kerry pledged to wage a more effective war on terror, a promise that Barack Obama would later echo when he vowed to get out of Iraq and focus on Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. But no one went after Bush as Trump has now.

Robert Shrum, a top consultant to the Kerry-Edwards campaign, says that no one in the camp went "within a thousand miles" of trying to blame Bush for 9/11.

"You have to remember this was pre-Katrina," Shrum tells Newsweek. Bush hadn't yet been pilloried by critics to the degree that he would be after the hurricane. "One thing people gave Bush a lot of credit for was what he had done to keep the country safe," Shrum says, adding that there was "no appetite" among any significant part of the electorate for trying to broach the subject, even though much had already been written about whether the president failed to pay attention to the intelligence briefings.

Bush would frequently accuse Kerry of minimizing the threat of terrorism. In Shrum's words, his strategy was to frame the entire election as a "9/11 referendum." Blaming an incumbent whose popularity was based on his commitment to defending the homeland could have played into the narrative that the Democrats were unpatriotic, however unfair that charge might have been. In a debate in Florida, Bush was asked whether the risk of another terror attack would go up if Kerry was elected.

"No, I don't believe it's going to happen," he replied. "I believe I'm going to win."

Bush gets all the credit for uniting the nation after 9/11, but it's possible that the nation united itself. Shrum said that it's likely the public would have rallied around the president regardless of party politics. A Newsweek poll in the post-9/11 issue found that an overwhelming majority of Americans favored retaliatory bombings even at the cost of civilian lives, but before the Ground Zero rubble was even cleared there was confusion about where to strike. Polls showed that Americans simply wanted to act. In 2003, the removal of Saddam was supported by Congress, with almost no one questioning whether action against a totalitarian state was commensurate with the threats America faced at home from stateless actors. As late as 2008, the Republican nominee for vice president, Sarah Palin, believed that Saddam had been behind the 9/11 attacks. Bin Laden, the head of A-Qaeda, remained at large until 2012, long after Bush left office.

In 2004, Shrum says, putting Bush's vigilance up for debate seemed like a "fringe tactic," and the mere suggestion never came up as a viable political strategy. But back then there was no candidate like Trump, whose tactics Shrum calls "ugly."

Even if the Bush's administration wasn't to blame for the attacks themselves, there's little doubt that Bush's national security priorities told a story of unpreparedness. According to the 9/11 Commission, the narrative arguably applied to Clinton as well.

But how would an Al Gore administration have responded? Would Gore have taken the advice of a foreign policy wing headed by Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney and Paul Wolfowitz by taking out Saddam?

More important, would Gore have received the same widespread support as Bush? It's hard to imagine the Limbaughs, O'Reillys and Hannitys of the post 9/11 world giving a Democratic president a free pass for attacks that happened on his watch. "The predictable response" from those figures, Shrum says, would be to blame the president. But he adds that this type of rhetoric would be bound to backfire in the aftermath of a national tragedy.

In discussing 9/11, Jeb might have been posing the right question when he asked Trump if he remembered the rubble. Now that Ground Zero is further from the collective memory than it was in 2004 or even 2008, the number of people siding with Trump is much higher than it would have been if Kerry had made the same arguments.

Another Back to the Future scenario: What would have happened to an incumbent Gore in 2004? Would he have gotten the same free pass from Republican challengers? Would the politics of fear have been the politics of blame instead? Would avoiding war in Iraq have led to an earlier killing of bin Laden?

Whether or not he could have done more, there's little doubt that George Bush has benefited from a certain taboo in American politics. Pearl Harbor was arguably much more foreseeable in December 1941, with all of Europe engulfed in war and the U.S. having taken strong economic action against Japan. The country rallied around FDR, but there was a commission, headed by Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts, that placed considerable blame on the Navy.

Trump's attacks on Jeb have everything to do with politics and nothing to do with foreign policy knowledge, but the second debate proved that the "on your watch" rule of modern politics is what people are paying attention to. As Shrum puts it, there's a chasm of difference between saying "it happened while you were there, so it's your fault" and the reality of foreign policy. It happens to be expedient for Trump to blame George because he is the brother of a rival candidate. For everything else that has gone wrong in the Middle East and at home, the Republicans will not hesitate to blame Obama.

"I blame Osama bin Laden and Al-Qaeda," Shrum says.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jack Martinez is a writer from Great Falls, Montana. He attended Stanford University, where he studied the Classics and received ... Read more