Normally the White House likes to take credit for freeing an American citizen from foreign captivity. Then again, there's been nothing normal about the case of Sabrina De Sousa, a former CIA officer who was convicted by an Italian court over six years ago for her part in the agency's kidnapping of a terrorist suspect in Milan in 2003.

De Sousa, who was freed Tuesday from a Portuguese prison where she was awaiting extradition to Italy, has always maintained her innocence in the case, which was the subject of a sensational 2009 trial. She and 25 other Americans, all but one CIA employees, were convicted in absentia for their roles in snatching an Egyptian cleric off a Milan street and transporting him to Cairo. Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr, known more widely as Abu Omar, says he was repeatedly tortured while under interrogation there. He was released in 2007 and convicted of terrorism charges in absentia by an Italian court in December 2013.

De Sousa, the subject of an international arrest warrant since her conviction, was detained as she tried to transit the Lisbon airport from the U.S. en route to visit her mother in India in October 2015. (De Sousa was born in the former Portuguese enclave of Goa.) She was freed shortly afterward but ordered to stay in Portugal pending a decision on her extradition.

That transfer appeared imminent on February 20, when De Sousa, 61, was picked up by Portuguese police and taken to a prison three hours north of Lisbon. Nine days later, she was transferred back to Lisbon for the handover to Interpol agents and transport to Italy.

"The guards came to get me late at night, saying I had to call my lawyer," De Sousa told Newsweek. He told her, "I was still going to Italy in the early morning, but not to prison."

Italian President Sergio Mattarella had shaved one year off de Sousa's four-year sentence, essentially reducing it to a misdemeanor and requiring only a term of community service, which she can carry out in Portugal.

De Sousa is the only CIA operative to see a jail cell in connection with the capture of Abu Omar, just one of hundreds of such so-called "renditions" that landed terrorist suspects in secret interrogation facilities, called black sites, and the U.S. military prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

She maintains she was a "scapegoat" for an unnecessary and ill-planned operation that was pushed by the CIA's then–station chief, Jeffrey Castelli, and green-lighted by Condoleezza Rice, President George W. Bush's national security adviser.

"There's one burning mystery," she told me in a 2012 interview for Foreign Policy magazine. "What case did Castelli make to render Abu Omar? He was under investigation by Digos," the Italian counterterrorism police. "He was not a clear and present danger, or they would've picked him up. And why did Egypt agree to take him, and why did they [the CIA] give him to a state sponsor of terrorism?"

Part of the answer, she said, was that Castelli had a "burning ambition" to impress superiors by capturing Omar. The spy agency's silent complicity in his disappearance unraveled when Omar called home to Milan when he was released and described what had happened to him. Italian police, eavesdropping on the conversation, quickly used records of cellphone tower communications to trace the calls to the CIA kidnapping team.

Castelli, who was sentenced in absentia to seven years in jail, is no longer a CIA employee; he has not responded to several previous attempts for comment and could not be reached Wednesday.

As is often the case involving the CIA, the U.S. government had nothing to say about De Sousa's reprieve this week. The CIA has consistently refused to comment on the case. A State Department spokesman referred Newsweek to the White House for comment, but officials did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Yet Pete Hoekstra, a former Republican representative and ranking member of the House Intelligence Committee who took up De Sousa's cause, claims she would not have been released "without extraordinary help from the Trump administration." Hoekstra told Newsweek he began lobbying officials in the Donald Trump campaign, and later the transition, to do something about the former officer's predicament. He had a number of friends in the national security apparatus from his time on the House Intelligence Committee—people like Michael Flynn, the recently departed White House national security adviser, fellow former Representative Mike Pompeo, now director of the CIA, and former Senator Dan Coats, the new director of national intelligence. And it didn't hurt that he had chaired Trump's Michigan campaign.

"I just said this was terrible that she should go to jail for something that was approved by the National Security Council and probably President Bush himself," Hoekstra said. "They recognized this had to be a front-burner issue," he said. "The optics" were bad. "You don't want a CIA case officer sitting in an Italian jail."

Hoekstra said he kept administration officials apprised of De Sousa's situation "in real time" as the day, and then hour, for her extradition grew near. "I was convinced that Wednesday morning she would be transported back to Lisbon and onto a plane to Italy," he said. And so was she. Her husband, a retired Department of the Army employee who had joined her in Portugal, packed her suitcases with only the light clothing she had. "It was warm here," she said, "and I dreaded freezing in Milan."

The next morning the guards came. She was handed over to Portuguese Interpol officials, who gave her the news: She would not be going to Italy after all.

Hoekstra gives all credit to Trump. "They got done in six weeks what Obama couldn't get done in seven years," he said.

A former Obama administration official rejects that claim. "The notion that anything was suddenly solved in the last month is inaccurate," he told Newsweek on condition of anonymity to discuss the still-highly classified case. "The U.S. government has been working with the Italians on pardons for certain individuals for years."

De Sousa's spirits have brightened considerably since her release, but she remains bitter at Obama administration officials. Since she was under cover at the Milan consulate as a State Department officer, she said they should have invoked diplomatic immunity in her case and defend her. (Actually, consular officials do not have the same level of immunity as diplomats, according to the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training.) In 2009, she sued the department and then–Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, saying she had suffered "significant emotional, professional and economic harm, including, but not limited to, possible criminal or civil liability."

The State Department—just like the Italian prosecutor in her case—denied she was covered by diplomatic immunity, and she lost the suit. In 2013, in an interview with McClatchy, De Sousa finally publicly acknowledged she had been a CIA employee, earning the wrath of her former employer.

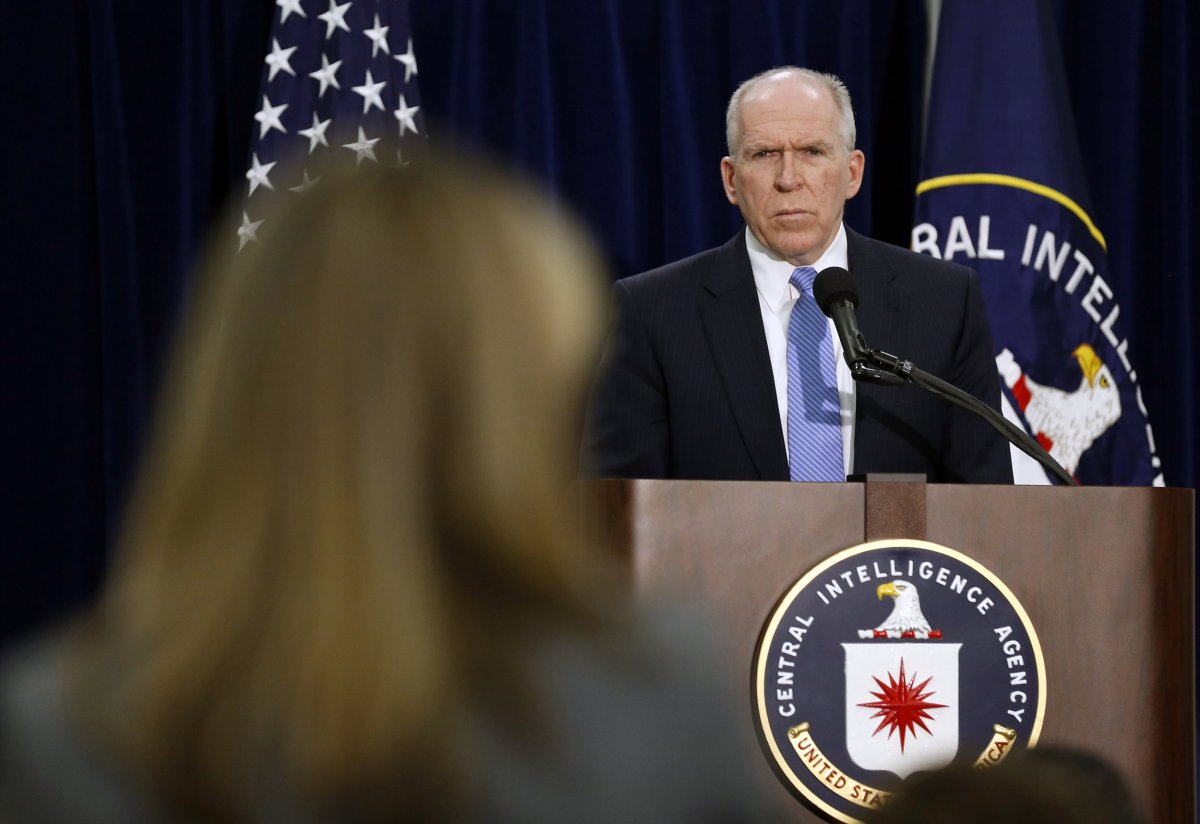

Neither President Barack Obama nor his CIA Director, John Brennan, tried to intervene with Italy to get her a pardon, she and Hoekstra maintain. "The message is that the president can throw you under the bus," she said in the Foreign Policy interview. Hoekstra said his Portuguese contacts told him that Brennan met with officials there twice last year and did not bring up her case.

The former administration official declined to concede that the CIA was in any way involved with the widely publicized case, but said, "Former Director Brennan worked this issue—an inappropriate Italian government criminal action against a U.S. diplomat—while he was at the White House and at the CIA. Hoekstra is dead wrong."

De Sousa doesn't see it that way: "S.O.P for CIA," she said in a typed message Thursday. Standard operating procedure. "Punish those who push back."

For whatever reason, the agency disavowed her, she thinks. Just like with the fictional CIA, in Mission Impossible. "As always, should you or any of your I.M. Force be caught or killed," the boss always said, "the Secretary will disavow any knowledge of your actions."

Turns out, it's the only spy movie that was really true.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.