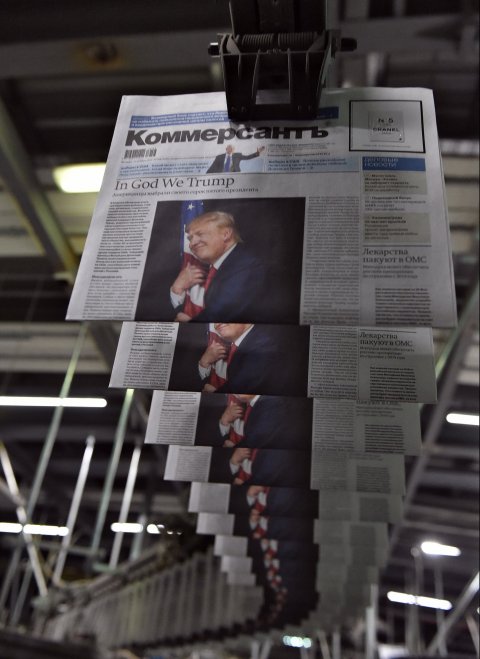

Last November, on the night of the U.S. presidential election, the mood in the Union Jack Pub in Moscow was jubilant. A select group of Russian media executives, pro-Kremlin activists and Duma members watched with mounting excitement—and joyful disbelief—as Donald Trump's Electoral College votes climbed toward victory. Reverently displayed in a corner of the bar stood a specially-commissioned triptych of oil portraits, in heroic Socialist-realist style, of Trump, France's Marine Le Pen and Russian President Vladimir Putin. A senior producer from Tsargrad TV, Russia's patriotic, Orthodox TV channel, pointed to the trio in jubilation. "Tomorrow's world belongs to them!"

Today, that new world order is nowhere in sight. The U.S. Congress has broken up the Trump-Putin bromance and forced the American president to sign the most punitive economic sanctions ever imposed on Russia to punish Moscow for meddling in Ukraine and Syria, along with its U.S. election-related hacking. And since the revelations about possible collusion between the Trump team and the Kremlin have begun to snowball toward an impeachment crisis, the American president's once effusive praise for Putin has vanished.

The collapse of the Trump-Putin mutual admiration society—potentially the world's most politically important relationship—is a story of unrealistic Russian hopes, badly-thought-out U.S. gestures and the Kremlin's misguided attempts to interfere in American democracy. Putin believed Trump was a man with whom he could do business, a pragmatist willing to overlook Moscow's annexation of Crimea, support for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and warmongering in eastern Ukraine; someone who would allow the Kremlin a free hand in exchange for Russian support against terrorism. Trump had long admired Putin's authoritarian leadership and envied his dictator-like approval ratings. On the campaign trail, he also had viewed praising Putin as a useful, if minor, tool in his arsenal of anti-Clinton invective. "I think I would have a very, very good relationship with Putin," Trump said in September 2016. "And I think I would have a very, very good relationship with Russia."

Both men were very wrong.

Anyone but Hillary

The recent media narrative in Washington, D.C., has been that Russia worked hard, using hacking, propaganda and disinformation, to get Trump into the White House. That's not the whole truth. The Kremlin's earliest and most urgent priority was to get anyone but Hillary Clinton elected. At least a year before Trump became a viable candidate, Russia began trying to undermine the Democratic Party and its likely presidential candidate. The Kremlin had loathed Clinton since late 2011, when Putin accused her of "sending a signal" to hundreds of thousands of activists who turned out across Russia to protest the former KGB man's third presidential term. That hatred only increased when Clinton advocated tough sanctions against Moscow after it annexed Crimea in March 2014. "We thought anyone would be better than the Clintoness," recalls Leonid Kalashnikov, head of the Russian Duma's committee on the former Soviet Union and European integration.

The first Russian attack on Clinton's campaign—fake phishing emails sent to Democratic National Committee staffers—was flagged to the FBI as early as October 2015. A subsequent investigation discovered that around 4,000 targeted emails were sent by a Russian hacking group, nicknamed Advanced Persistent Threat 28 by U.S. law enforcement and later found to be linked to Russia's Federal Security Service. On March 19, 2016, the hackers got into the email account of Clinton's campaign chief, John Podesta. Months later, they published the emails they had stolen on WikiLeaks, using a flimsy set of decoy identities to conceal their origins. The revelations of squabbling among Democrats were mildly embarrassing to the former secretary of state and ultimately helped Trump—but the hacking effort came long before the real estate mogul's candidacy.

The Kremlin's love-in with Trump began in earnest after Super Tuesday, March 1, 2016, after he unexpectedly won seven states in the Republican primaries. Russia's state-controlled media began talking him up as a pro-Russian maverick who admired Putin. "We never believed that the U.S. establishment would ever allow [Trump] to win," recalls a senior Russian TV anchor and well-known Kremlin propagandist, who asked for anonymity when discussing the evolution of his show's political position. "But it looked like this man was interested in a deal. He seemed like someone who wanted to break down Washington's clichés about Russia.… Basically he looked like he could be nash —our kind of guy." Kremlin-controlled TV, along with its foreign-language mouthpieces RT and the Sputnik news agencies, began spinning the line that Trump was a fan of Putin and an enemy of a supposedly Russia-hating Washington establishment. Meanwhile, on the dark side, Russian hackers began creating bots to boost Trump's Twitter numbers—whether on the Kremlin's orders or not hasn't been proved—and retweeting anti-Clinton memes like #crookedhillary. "Trump has said that he does not want to impose the American will on other sovereign nations," Vyacheslav Nikonov, head of the Duma's Committee on Education, told Newsweek at the time. "That's a world which I welcome."

Many Russians were thrilled by Trump's fondness for their supreme leader. As early as October 2007, Trump told CNN's Larry King that Putin was "doing a great job in rebuilding the image of Russia and also rebuilding Russia period." In 2013, when Trump brought the Miss Universe pageant to Moscow, he wondered in a tweet if Putin would "become my new best friend." (Trump also falsely claimed that he had met Putin during his visit.) And in December 2015, on MSNBC's Morning Joe, Trump defended the Russian leader against allegations he had ordered the killings of journalists by retorting that "our country does plenty of killing also." Most attractive to Russians was Trump's often-repeated insistence on the same kind of machismo that forms the basis of Putin's cult of personality. "I don't think [Putin] has any respect for Clinton," Trump said in July 2016. "I think he respects me."

Yet Putin was very cautious in his public remarks about Trump. In December 2015, he called the American a "bright personality"—though the word Putin used, yarky , was faint praise, conveying a distinct double meaning of "extravagant" or "high profile." Trump twisted Putin's phrase, transforming the Russian president into a fanboy. "He called me a genius," Trump claimed two months later. "He said, Donald Trump is a genius and he is going to be the leader of the party and he's going to be the leader of the world or something." By the time Trump won the election in November 2016, the world stage seemed all set for a major rapprochement between Moscow and Washington based not on political affinity or shared strategic interests but on the attraction of two oversized egos.

"The time has come for a new era in Russia-American relations," crooned ultranationalist politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky as he toasted Trump's victory with champagne live on Russian TV—hours after the entire Duma had broken into applause when the news was officially announced. "There will be mutual respect.… Two great nuclear powers will meet again as equals."

The Honeymooners

Before the grand Trump-Putin reset could take place, there remained the small matter of Russia's election hacking. Silicon Valley cyberexperts and law enforcement had already begun to build a powerful—if circumstantial—case linking the July WikiLeaks email dump to the Kremlin. In fact, Trump had publicly called on Russian hackers, "if you're listening," to find Hillary Clinton's missing emails. Trump later called the remarks "a joke." But when news emerged that Russians had also attempted to break into electoral registers and other voting infrastructure, the question of Russian meddling—and the possible collusion between members of the Trump team and Moscow—soon ceased to be a joking matter. At the same time, an extraordinary—and completely unsubstantiated—story surfaced suggesting that Russia may have videotaped Trump in a compromising position with prostitutes during his 2013 visit. It was followed by other revelations—which the White House eventually acknowledged—of contacts between members of Trump's family and a Russian lawyer who claimed to be bringing compromising material on Clinton from Trump's Miss Universe partners, the Agalarov family. In the wake of his election victory, Trump soon stopped exalting Putin.

Even as anger and evidence mounted at Moscow's electoral interference, the Kremlin kept hoping its dangerous gambit was going to pay off. Just as Putin had denied sending troops into Crimea or that Russia had played a role in shooting down a civilian aircraft over Ukraine, he indignantly denied any involvement in the hacking effort. And when the outgoing Barack Obama administration responded to that effort in late December, saying it planned to expel 35 Russian diplomats, shutter two diplomatic compounds and impose new sanctions, the Kremlin resisted the temptation to respond with similar measures. According to FBI phone intercepts leaked to The Washington Post , Sergey Kislyak, Russia's ambassador in Washington, spoke in person and by phone to both Trump's newly appointed National Security Adviser General Mike Flynn—a Russian sympathizer since his days as a pundit for the Kremlin-owned RT channel—and to Trump's son-in-law, Jared Kushner. Putin, satisfied by Flynn's apparent assurances that the new administration would fix the diplomatic and political damage, held back on the traditional tit for tat. "We gave the Trump administration a chance to change the course set by Obama," Nikonov tells Newsweek . "We did nothing to retaliate."

But the fix never happened. Faced with allegations of improper ties with Russia, Trump was forced to prove he wasn't beholden to Moscow by—reluctantly—firing Flynn. He then bombed a regime-held airbase in Syria, in defiance of Putin's support for Assad. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson made some attempts to get the Russian Embassy's dachas reopened in May, but "came up against strong opposition from the intelligence community," a senior U.S. State Department official told Newsweek during a background briefing.

By the time Putin and Trump had their first face-to-face meeting at the G-20 summit in Hamburg, Germany, in July, the relationship Trump had once hoped for was definitely off the agenda. To Trump's ire, a special counsel investigation in Washington was digging into possible collusion between members of his campaign and the Kremlin—along with alleged financial ties between Trump's business empire and laundered Russian money. The two-hour meeting in Hamburg was "constructive" and "substantive," says one senior Russian foreign ministry official with direct knowledge of it, who asked for anonymity because of the sensitivity of the matter. But what Tillerson called "a very robust and lengthy exchange" over allegations of Russian hacking—which Putin again denied—eclipsed the two sides' attempts to discuss a joint approach to Syria.

"[Trump] is a businessman, he wanted to get some concessions from Putin over Syria, Korea, Ukraine, to bring back something in order to tell his voters that he's struck a deal," Konstantin Kosachev, head of the Committee on International Affairs of the Federation Council, Russia's equivalent of the Senate, tells Newsweek . "But he couldn't. Putin would not bend." As for Trump, any concessions to Russia would have been seen as a sign of weakness—or collusion. "Trump couldn't say anything" says Kosachev. Instead of being the start of a budding friendship, Hamburg marked little more than the exchange of platitudes by two men trapped by circumstance—Trump stymied by the Russiagate allegations, and Putin paralyzed by the fear of appearing weak.

By the time Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov went to Washington on July 17 in a last-ditch attempt to negotiate a deal over the shuttered diplomatic dachas, the U.S.-Russia relationship seemed almost as icy as it was during the Cold War. "There remain very few areas where we can discuss constructive cooperation, unfortunately," Ryabkov says. "There seems little willingness on the American side to start a new chapter." Ryabkov flew home to Moscow with nothing to show for his efforts. And the relationship between the countries would only get worse.

'Total Impotence'

It was Congress that finally ended any chance of a Trump-Putin reset on July 25, when both chambers overwhelmingly passed a bill enshrining Barack Obama's economic sanctions against Moscow into law, recommending even more sanctions against Russia's energy sector and forbidding the president from easing them without congressional approval. The law struck at the very thing on which the Kremlin had hung its hopes—Trump's authority to create his own Russia policy. Top officials in Moscow were quick to grasp that Congress had effectively neutered the president, at least as far as the Kremlin was concerned.

"Trump's administration has demonstrated total impotence by surrendering its executive authority to Congress in the most humiliating way," wrote Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev in a Facebook post. "The U.S. establishment fully outwitted Trump.… The hope that our relations with the new American administration would improve is finished." Or as Sergei Zheleznyak, deputy chair of the Duma's Committee on Foreign Affairs, tells Newsweek , "Trump is no longer in charge. What is there for Putin to talk about with him? What is the point of talking to Tillerson if he comes to us, when [Putin] knows that [Trump] cannot remove sanctions?"

The Kremlin was in a bind. Putin, striking a tone of regret, called the sanctions "insolent" and promised "an adequate response." The problem was that there was no response Russia could make—other than nuclear war—that could really hurt America. So Putin settled on a riposte that addressed the December diplomatic spat rather than the sanctions. He ordered the reduction of staff at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow to 455, matching that of the Russian Embassy in Washington, and the confiscation of a U.S.-rented dacha in suburban Moscow. Russian media presented Putin's retaliation as the "expulsion" of 700 diplomats, but it was nothing of the sort. According to a 2013 report by the U.S. inspector general's office (the latest figures publicly available), only 345 of the embassy's staff were American. Putin's "tough" measures won't result in a single U.S. diplomat packing his or her bags—but it will lead to more than 800 Russian Embassy employees losing their jobs.

"This is a way to tell Congress how you can and how you can't treat Russia," says Zheleznyak. With unintended irony, he's right—Moscow is essentially powerless to retaliate. Nikonov speaks of withdrawing Russia's $109 billion in U.S. Treasury bonds in retaliation for sanctions. But with the turnover of T-bills on Wall Street running at $490 billion a day, it would take half a morning to liquidate Russia's entire position without leaving a tremor on the market. Another option would be to end cooperation between NASA and Russia's space agency Roscosmos, on whom the U.S. has relied for sending astronauts to the International Space Station since American scrapped its space shuttle program in 2011. But Moscow slashed Roscosmos's 10-year budget from $64 billion to $21 billion in 2014. And without the estimated $3.96 billion that NASA is due to spend on astronaut flights, the Russian space agency would struggle.

The official Kremlin line on the new sanctions is that Russia will proudly survive—just as it survived other foreign aggressions. The day after news of Congress's vote broke, Russia's Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin published a video clip on his Facebook page of the "The Fortress of Brest," a patriotic song about the defenders of a Soviet border city struggling against Nazi invaders in June 1941. Rogozin's siege mentality seemed less of an overreaction when Vice President Mike Pence went to Estonia and Georgia days after the congressional vote and warned against further aggression from "your unpredictable neighbor to the east."

"These sanctions are the institutionalization of the new Cold War," says Nikonov. "We have always lived with external aggression, and this piece of paper is part of the same pattern. We were under sanctions for decades in Soviet times. Now we are now obliged to solve our own internal problems ourselves. These sanctions will make us stronger, more united, and more independent."

Communist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov even seemed to welcome the new sanctions, hailing them as an opportunity for Russia "to rebuild our own economy, relaunch our technology and science, aircraft building and automotive industries," he tells Newsweek . "We have been dependent on the West for too long."

The truth is more prosaic. The sanctions—now enshrined in law—prevent a swath of Russian companies from raising capital on international money markets and ban American firms from doing business with them. That poisons Russia's long-term economic development plans and hurts a variety of key industries, especially capital-intensive ones like oil and gas drilling. In practice, though, they haven't dented Putin's 80 percent–plus approval ratings. The average Russian consumer hasn't felt much economic pain, primarily because of swift counter-sanctions in 2014 that banned the import of all food products from the U.S. and EU and isolated most domestic consumers from drastic price increases. And despite the sanctions and falling oil prices, Russia's economy grew 0.3 percent in the last quarter of 2016 after seven consecutive quarters of shrinkage, according to Bloomberg.

The senior U.S. official in Moscow claims the new sanctions are "an 'Oh, shit' moment for the Russian elite—they finally realize that their leadership is taking them in a bad direction." But the truth seems to be the opposite: While the Russian economy sputters, Putin has thrived on his opposition to America and his ability to market himself as a leader who stands up to foreign aggression. The collapse of his attempted detente with Trump, the perceived unfairness of the new sanctions and constant propaganda about the "anti-Russian hysteria" in Washington have, for the time being at least, boosted Putin's patriotic credentials.

Patriotic, that is, for public consumption. In reality, in Kislyak's signature phrase, "much more unites America and Russia than divides us." For all the bluster about independence, Moscow is far more dependent on the West's financial system and technology than vice versa. And Putin cannot afford to truly cut his country off from the West because so many of Russia's elite keep their money—and in many cases their families—there. Until recently, even Putin's daughter lived in the Netherlands. And the Panama Papers revealed dozens of names of key Putin acolytes with unexplained fortunes salted away offshore—such as Sergei Roldugin, a famous cellist and old friend of the Russian president, who allegedly owns companies worth $2 billion. As Konstantin Remchukov, editor-in-chief (and former owner) of the daily newspaper Nezavisimaya Gazeta, puts it: Russia remains "deeply and inextricably connected to the economy of the West."

In the short term, the collapse of the Trump reset may have left Putin politically unscathed. But in the longer term, the Russian leader has dwindling options. Putin may have hoped that a personal friendship with Trump would free him of his sins in Ukraine and Georgia. Instead, Washington's line on Moscow is toughening by the day. Kurt Volker, a former ambassador to NATO, head of arch-Russia hawk Senator John McCain's foundation and strong advocate of arming Ukraine against Russia, has just been appointed as America's special representative to Kiev. Most members of Trump's Cabinet also reportedly back sending lethal weapons to Ukraine, which is likely to turn the conflict in Donbass into a full-fledged proxy war between Washington and Moscow.

Since Trump's reluctant signing of the sanctions bill—which the White House called "seriously flawed…and probably unconstitutional"—many Russian officials have argued that Trump wants to be friendlier with Moscow but is prevented from doing so by Washington hawks. "Congress is seized with a shark-like madness—they're hungry for blood," tweeted Russian Senator Alexei Pushkov. "They're tying Trump's hands, angering the EU, pushing Russia away." Others hope the new sanctions interfere with the ability of EU companies to do business in Russia, which will create conflict between Europe and the U.S. that will work to Moscow's advantage.

Both hopes seem pretty vain. Even if Trump continues to harbor a secret love of Putin, it has become politically impossible for him to make nice with Moscow for fear of more accusations of collusion. And the White House has already made it clear that all future sanctions recommended by Congress will be made "in consultation with our allies," limiting the chance of an EU-U.S. split over Russia (the bloc has its own sanctions in place against Moscow, also over Ukraine).

Putin and Trump's failure to launch a new era of post-post–Cold War cooperation will cost both men dearly. The Russian leader faces deepened international isolation and a slow economic strangulation. But it's worse for Trump. His words of praise invited Putin's ill-fated attempt to help get him into the White House. There's no evidence, so far, that Trump directly abetted that effort. But Putin's embrace may yet prove politically fatal for the mogul who just wanted to be the Russian strongman's "best friend."