Updated | A technological revolution killed the Whig Party in 1850. A new one is blasting the GOP into splinters in 2016.

Amazingly, none of the presidential candidates talk much about technology, yet our software-eats-the-world whirlwind drives everything that's cleaving the country and throwing its politics into chaos. The parallels to the dynamics of the 1850s are a little scary. After all, the Whigs' self-destruction was a prelude to the Civil War.

Like today, the technological revolution in the mid-1800s ushered in a disruptive new era of connectivity, and transportation technology was key. Before the 1800s, getting anywhere—or exchanging any information over distance—involved horses, mud roads or boats. Movement was so hard that almost all business in America stayed local and small, and much of it was centered on agriculture.

Then, starting around 1810, the country paved roads and built canals. Robert Fulton invented the steamboat in 1807, and within a couple of decades mountains of goods were flowing upstream. The monster agent of change was the railroads. The country built rail lines with the same alacrity that would go into building the Web during the dot-com boom. By 1860, the U.S. boasted more miles of rail than the rest of the world combined.

Oh, and in the 1830s Samuel Morse invented the telegraph. By 1860, telegraph lines spanned the continent. You couldn't quite sit in Boston and Skype your dad at the California Gold Rush, but prices and business data could cross states in a flash. It was an information transformation.

All of this changed life and economics in ways we can relate to today. News and people traveled faster than anyone had ever experienced. The cost of moving products and services plummeted in the same way Amazon or cloud-based apps have driven down distribution costs. Such forces made it easier for big companies in one place to serve customers everywhere. The technology "made possible a division of labor and specialization of production for ever larger and more distant markets," wrote James McPherson in Battle Cry of Freedom, his epic Civil War history. So by 1850, factories were making certain types of craftsmen obsolete, department stores were driving local shops to close, and people found themselves losing jobs to someone far away.

Much like today, money in the early 1800s flowed to the new economy and away from the old economy. Capitalists who owned production got richer, and laborers lost power. The gap between rich and poor widened.

Cue the kind of anger Donald Trump is tapping into now.

And here's the twist: In 1850, New England was essentially Silicon Valley, and the Northern states created and embraced new technology while the Southern states held tight to agriculture and a way of life that also happened to include the moral outrage of holding slaves. A telling statistic from McPherson: Of the 143 important inventions patented in the U.S. from 1790 to 1860, 93 percent were from Northern "free" states. He wrote, "The North appeared to be racing ahead of the South in crucial indices of economic development."

Slavery turned into a flashpoint issue, but the real unrest boiled up from this giant economic rift. Technology transformed the North into an industrial economy while the South was anchored in an agricultural economy, one that couldn't operate without slavery. The North had a population that saw the advantage in embracing technology and progressive ideas (including that slavery was bad) and moving forward. The South's way of life and economic fortunes rested on keeping things as they'd been. The South viewed the North as a threat.

Look today at red states vs. blue, or even Trump supporters vs. "establishment" Republicans. Those divisions broadly define where digital-cloud-mobile technology and the modern economy work in favor of the population vs. where they work against them. Trump says "make America great again," which, to his supporters, means "make America what it used to be." To people whose livelihoods have suffered because of economic shifts ushered in by technology, moving backward looks better than moving forward—not just in economic issues but in social mores as well.

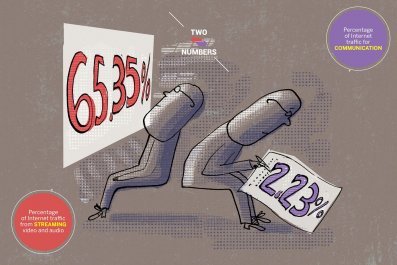

The big difference between now and then is that instead of that shift from agriculture to industry in 1850, today we're seeing a shift from industry to software. The more that software can leverage the work of fewer humans, the fewer humans are needed for work, and the more profits flow to owners of the software. One industrial company, United Technologies, provides an example. At 218,300 employees, the company's workforce hasn't grown in seven years, even while revenue jumped from $42.7 billion in 2005 to $57.7 billion in 2012. That's $15 billion not being spent on more employees. Productivity created by technology tends to put more earnings into fewer hands.

Software is eating the world, as investor Marc Andreessen famously put it. The makers of the software are eating the money. The lives of many of the people in tech hubs such as Silicon Valley, Seattle, Boston, New York and Washington, D.C., are going one way. The lives of many people in industrial or rural areas are going another. It may not be a North-South divide, but you can see a break widening between the coasts and the nation's interior.

Trump has become the voice of those technology has hurt. He's not just a protest vote; he's a rebel vote. It's a rebellion against Republican leaders who failed to conserve industrial jobs and a more traditional society. It's not that different from the Whigs in 1850, when the party split between "Conscience" Whigs, who were pro-industry and anti-slavery (and thus threatened the whole Southern economic house of cards), and "Cotton" Whigs, who would fight to preserve an increasingly outmoded way of life.

The party cracked in two, and the Northern Whigs joined the new Republican Party, which put Abraham Lincoln in the White House in 1861. Shots were fired on Fort Sumter soon after, starting the Civil War.

The current rift in America isn't going to mend if Trump wins, or loses. Look at what's coming. Autonomous vehicles will eat driving jobs of every kind. Artificial intelligence will eat rules-based white-collar jobs like accounting. Block-chain technology will result in software-based contracts that eliminate the need for mortgage brokers and lots of lawyers. Factory work will be diminished by 3-D printing. The total disruption of the 20th-century way of life is inevitable and far from over.

Of course, like the tech revolution of 1850, ours should eventually create enormous opportunities we never dreamed possible. It is the path to wealth and comfort for every part of the country and every level of society. The best news is that, like in 1850, the U.S. leads the world in all of the important technologies. If we as a people can get through this, we won't make America great "again"—we'll make it into something cooler and better than it's ever been.

Somebody has to step up and lead us through this transition—rally us and help us all benefit from the great inventions of our time. I can only imagine that if some farsighted leader in 1860 told Southerners that they were a generation away from cars, airplanes, electricity and the National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, they might have worked out a way to end slavery and skip a devastating war.

Correction: Due to an editing error, a previous version of this story had a garbled explanation regarding who fired the first shots at Fort Sumter.