It was 2009 and the American landscape was bleak: The housing market had crashed, millions of people were in foreclosure and stocks had keeled over a cliff. Beth Wood saw her life savings, around $325,000 in home equity, evaporate in a matter of months as the value of her suburban San Francisco house plummeted. Her husband, a United Airlines employee, had lost his pension in that company's reorganization a few years prior. And Wood was dealing with a personal crisis: Her mother was dying of cancer and spending her final months in their home.

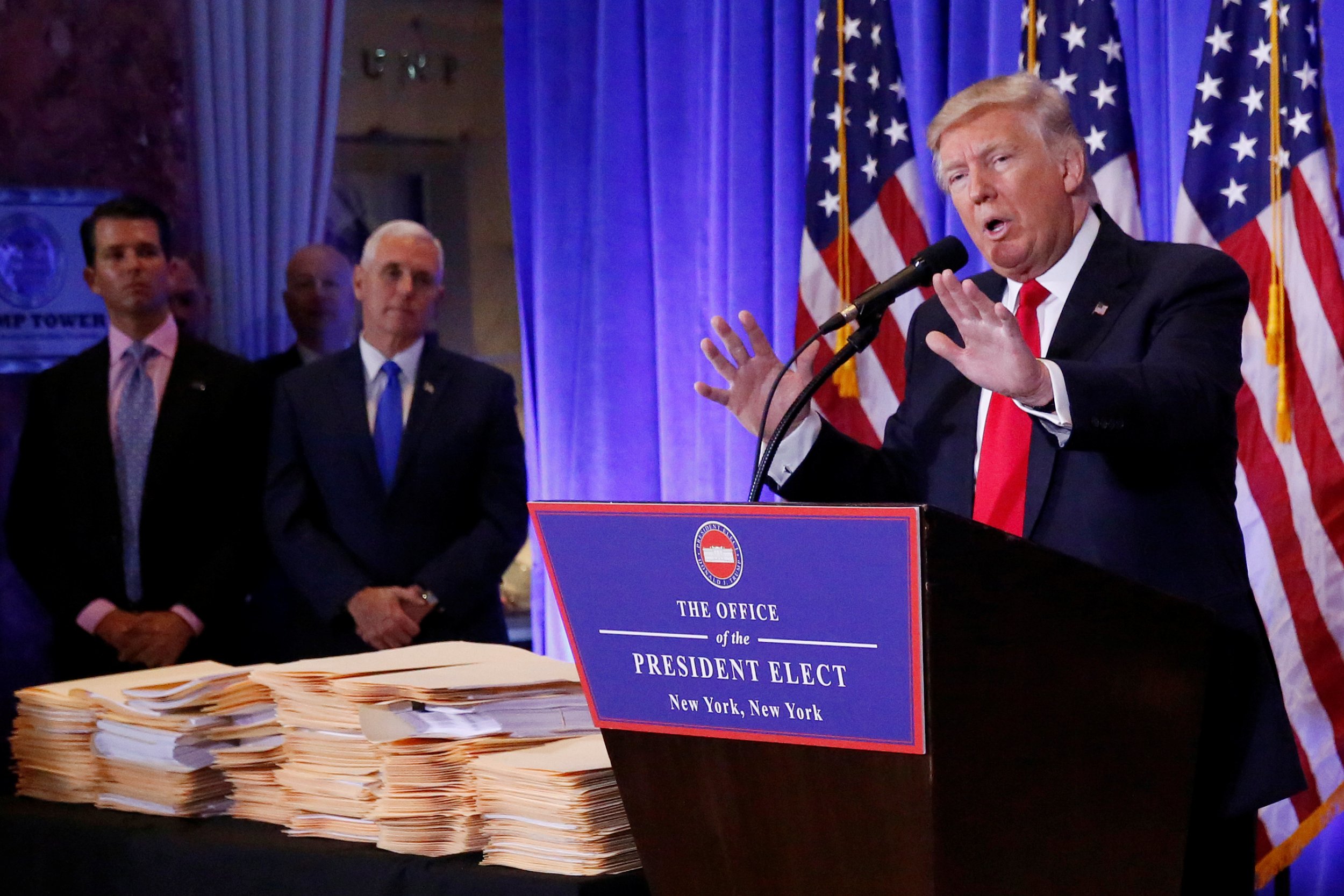

Related: Summer Zervos files defamation suit against Donald Trump, three days before inauguration

In the midst of what she calls "escalating catastrophes," Wood began casting around for a way to get her financial situation back in order. One day, she noticed an ad for a Trump University seminar. "Could You Be My Next Apprentice?" it said, over a picture of Donald Trump in a suit and tie. Wood had never seen The Apprentice TV show, but she knew enough about the New York magnate's reputation to be interested in the free session, which she attended. There, a speaker promised to teach Trump's secrets to success in real estate. Subsequent Trump teachers promised to share the names of "hard-money" lenders to those who signed up for more sessions and paid for them. Believing she could jumpstart a new, lucrative career in buying and selling property, she forked over $34,995 for the top, Gold Elite, plan.

Wood eventually spent more than $70,000 on Trump University "seminar and software investments" before she realized that it offered no secrets to success, and like hundreds of other "students" she complained to authorities. On Tuesday, Donald Trump forked over $25 million to partially refund Wood and others who paid for live seminars between 2007 and May 23, 2010.

Wood and her husband ended up owning five tiny, dilapidated houses in Texas, and paying 14 percent interest on the loan. Their Trump U mentor—supposedly "handpicked" by Trump—had steered them to what he'd described as a "once in a lifetime sweet deal." What he didn't tell them was that he received a $10,000 kickback from the deal, and afterward he refused any meetings with them and Trump U's promised support evaporated.

By the time the Woods extricated themselves from the real estate investment mess, they lost over $80,000 on the real estate and their credit was ruined. They can't buy a home now because of their credit woes, and Wood's 68-year-old husband can't afford to retire.

"It was a scam from beginning to end," Wood says.

On the other side of the country, in a small town on Long Island, Carol Burke (a pseudonym) was also emerging from personal crises. In 2009, after two decades in finance and litigation, she was laid off and given a $300,000 severance. The former chief financial officer had also lost a significant portion of her savings in the market crash of 2008. While casting around for how to wisely invest her severance money in a way that would allow her to start anew, her partner became sick with what would eventually be diagnosed as a rare cancer.

In November 2009, Burke attended a Trump U free session at a hotel in Manhattan. "I saw the ad in the New York Post," she says. "And I thought, Why wouldn't you spend an hour getting free advice from a billionaire?"

That hour—a pep talk describing a life of ease and riches unimaginable and promising information about secret sources of funding that Trump and his very wealthy friends had access to—convinced her to part with the nearly $35,000 for the Gold Elite program. A few weeks later, alarm bells went off during the first Gold Elite session, when rather than divulging the names of secret hard-money lenders, the speaker took the podium and gave a rousing speech about how wealthy he was. He then turned the attendees loose on the internet to do their own research. "We spent the whole day trying to find hard-money lenders," says Burke. "They didn't have anyone. We were looking online."

Burke stayed with the program until she realized that a commercial real estate seminar instructor didn't know what he was talking about. "He was telling us to do things that I knew were illegal under New York State law," she says. She went to the Better Business Bureau and filed a complaint, and then she demanded a refund from Trump U. When she threatened to bring audiotapes of the seminars to authorities, Trump U refunded 75 percent of what she'd paid out. Burke, who filed for bankruptcy in 2011, says her life savings dwindled while she was trying to follow her inexperienced mentor's instructions. "It never entered my mind it wasn't for real," she says. "I never thought somebody would do a fraud on this scale, and I wasn't prepared for it. I went in with my both feet and got sold."

New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman has called Trump University "an out-and-out fraud" and compared it to a "three-card monte" game that preyed on the most desperate. It thrived during the tenuous times just before and after the great American bubble burst, raking in around $40 million—of which, according to a Trump comptroller, Trump pocketed $5 million.

There were Trump University seminars coast to coast, in rented hotel rooms. Crews of Trump's advertised "handpicked experts" (he later conceded that he'd never vetted or even met them) would fly into town, rent an SUV, drive to the hotel, set up a cardboard cut-out of Donald Trump, cue up The Apprentice theme song and then lure in men and women, many of whose equity and investments had been erased by Wall Street's epic fail, and who were attracted to the great businessman's newspaper and TV advertising about sharing his secrets. Burke and Wood both said that other seminar industry professionals often took the stage at the Trump U seminars and marketed their own dodgy get rich quick programs.

Whether branded "Trump" or something else, a revolving cast of characters appears in many get-rich-quick scams, according to California lawyers Rachel Jensen and Amber Eck, who represented the class action plaintiffs. The operations usually last about three or four years before journalists, Better Business Bureaus and state attorneys general start investigating complaints. When the authorities get too close, they scatter. Since they work in rented halls, operators simply pack up their materials and later re-emerge under other names, in other halls, working with the same, all-American huckster's faith that a sucker is born every day.

Wood, Burke and the approximately 7,000 people who attended Trump University's live seminars between 2007 and 2010 paid between $1,400 and more than $35,000 to listen to speakers who often had little or no business experience; for plagiarized handbooks about how to make millions of dollars; and for software that didn't work. Eventually, hundreds complained to lawyers and agencies that they had received nothing for their money. The students came to understand that they were not attending a university at all but were marks in a nationwide up-selling operation. The secret to success was always another level away, and to get to it, they needed to buy more books and CDs.

One book they never saw was the Trump University Playbook, a behind-the-scenes blueprint for the "instructors"—salesmen actually—on how to identify the most lucrative and receptive potential "clients" at the hour-long free seminar, and then how to rope them into buying the premium three-day package, plus software and other programs. The playbook even included advice about how to behave if members of the media or representatives of attorneys general showed up.

According to science writer Maria Konnikova, in her book The Confidence Game, confidence games are most effective during times of crisis or transition. There is no typical victim of a con (anyone can be tricked, according to many studies), but many victims are people experiencing personal crises like deaths in the family, divorce or job loss. In times of crisis, the most stable people may in fact be the most vulnerable to cons. Patient, levelheaded people "will go a bit crazy in the wake of a major life change," she writes. "Their deception radar is off."

The language of the Trump U playbook—with chapter titles including "The Play," "The Art of the Set" and "The Roller Coaster of Emotions"—is straight from the dictionary of the confidence man. It outlines, almost verbatim, some of the tactics Konnikova describes in her book.

The best confidence games are meticulously planned. The Trump U playbook is extremely specific on the approach, which is called "the play" in con terms. The playbook instructs team members on such minutiae as what size car to rent at the airport, the size and temperature of seminar rooms, the placement of materials, the placement of chairs (not so far apart that people could isolate themselves) and the precise timing of when to cue the pump-them-up Apprentice theme song (as the doors open).

The playbook laid out specific duties for each team member. While the speaker was giving an upbeat talk, usually describing his or her path to unimaginable riches, another was assigned to work the edges of the room, studying the audience for signs of receptivity, and a third was stationed by the door, to ensure no one left without filling out a form that asked for, among other information, how much available funds were left on their credit cards.

Confidence games pique people's desire to be part of an exclusive group. The playbook advised salesmen to tell potential buyers that the program was "invitation-only" and that they might not get in. "The takeaway is there simply to remind the client that it is not their decision to join this program," the playbook states. "We know they need our program. They will begin to sell themselves to us; they will be climbing ever closer to the peak of the emotional roller coaster."

Confidence games play on people's emotions and usually leave their victims shaken, humiliated, embarrassed and blaming themselves for their ignorance. Trump's settlement—without an acknowledgement of guilt—doesn't erase the shame and distrust left by being duped. "Once you go through something like this, your confidence is shaken to the ground. You feel like a complete idiot," says Burke, now a real estate agent whose own house is in foreclosure. "I've done the best I can but there are so many fraudulent debt people out there and we don't know who to trust," says Beth Wood. "I'm so humiliated by this. I am probably the biggest fool there is."

Although the New York attorney general compared Trump U to a classic confidence game, Trump and his lawyers fought hard against the suits filed by attendees. When lawyers in California asked Trump in a 2012 deposition if he had ever seen the playbook, he said he didn't know. He personally and publicly chastised California plaintiff Tarla Makaeff, who left the lawsuit last March, as Trump was starting to win the Republican primaries. He also threatened to countersue the California lawyers and plaintiffs.

Trump lawyer Alan Garten did not answer emailed questions from Newsweek about why Trump settled, or whether he was aware of the similarities between the playbook and classic cons.

If Trump had not been elected president, the case might have dragged on for years, based on Trump's habit of fighting even losing cases to the end. Trump always maintained that 98 percent of people who took the classes were happy—as indicated on survey forms they filled out on the way out. Such surveys are known in seminar industry lingo as "smile cards." Participants are pressured to fill them out while still pumped up from the pitch. (In Burke's case, "We Are the Champions" was still playing through the speakers in the room.) The smile cards are crucial because they can be brought forth when people realize they've been fleeced and ask for their money back.

Two days after the election, during a hearing in the San Diego federal courtroom of U.S. District Judge Gonzalo P. Curiel (the judge Trump famously accused of being biased because of his Mexican roots), Trump's lawyer said he was "all ears" about reaching a settlement. By November 18, the parties in the California class actions and the New York attorney general had agreed to a settlement of $25 million, with $4 million going to pay New York fines.

San Diego lawyer Rachel Jensen, one of several attorneys who spent years representing the plaintiffs and class action members pro bono, calls the settlement "fair."

"It provides certainty that former students, many of whom are still paying off their credit cards, will get a substantial payment—as quickly as possible. If we had gone to trial, plaintiffs would have had to get a unanimous verdict against the president-elect of the United States," she says. "And even if the jury voted unanimously against Trump, we would have had to go through individual damages hearings for class members, which could have taken months or years, and then followed by lengthy appeals. It could have easily taken five to 10 years before any of the class members saw a penny."

People who paid for a live Trump University seminar or in-person mentorship can now request a refund. Jensen says the money could be disbursed as early as this summer.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Nina Burleigh is Newsweek's National Politics Correspondent. She is an award-winning journalist and the author of six books. Her last ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.