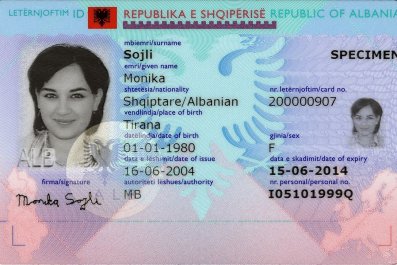

"Good art always has a sense of activism," says Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei, who was once detained for protesting his country's human rights abuses (officially, it was for tax evasion). After being arrested at the airport and confined in a tiny room under the constant watch of uniformed military police sergeants for 81 days in 2011, authorities kept his passport for four more years. When he finally got it back, he quickly left China.

Ai may be one of the world's best-known contemporary artists, whose works have sold for millions, but it's not hard to understand why he might feel some kinship with refugees. His childhood was spent in exile in remote regions of China after his father, a renowned poet, was accused of being a "rightist." His adulthood has been marked by clashes with his government, culminating in a detention he has called "mental torture."

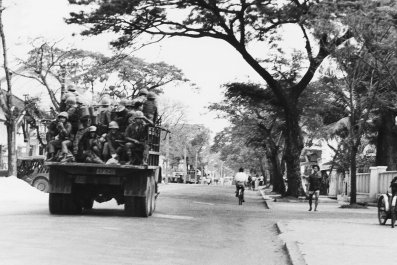

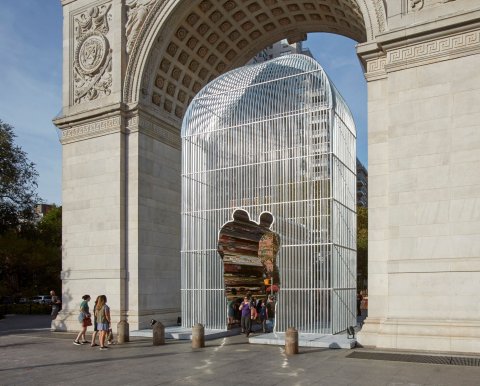

Ai has just unveiled two major works of activist art. His documentary Human Flow, a powerful and visually stunning evocation of the global refugee crisis, premiered Friday, just one day after the debut of his public art project Good Fences Make Good Neighbors, a group of monumental, site-specific structures, sculptures and banners in New York City, where he lived in the '80s. Good Fences is an effort to address the rise of nationalism and the closing of borders—and hearts—to refugees and immigrants; Human Flow illustrates his fundamental belief that humans need to protect one another: "Anyone who is being hurt anywhere in this world, we are all being hurt. We're all vulnerable."

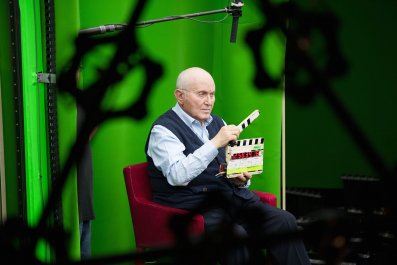

In early October, the artist visited New York to promote Human Flow and Good Fences. It was just after the opening of the Guggenheim Museum's "Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World," an exhibit of experimental and political art created following the Tiananmen Square demonstrations. Outraged animal rights activists had pressured the Guggenheim to pull three pieces by other Chinese artists—videos featuring pit bulls and pigs as well as an installation with live lizards and insects.

Ai talked to Newsweek about the museum's decision, what he hopes people will understand about the refugee crisis and how history might treat the wall President Donald Trump wants to build on the U.S.-Mexico border.

What did we lose when the Guggenheim pulled those pieces?

We all know different cultures and different locations have very different kinds of moral judgment. China is not the United States, China is not India, and we have to understand that. Cultural exchange is about looking at those differences. Of course, we're not saying it's right or wrong, because moral judgment makes art very narrow. The Nazis had very strong moral judgment in art. They would say many kinds of art were degenerate—abstract and surrealist art—and the healthy art was about the workers, socialist images. But as a result, German society became extreme. Any society trying to find the pure condition becomes extreme. So I'm saying in supporting those works, I don't like them or I don't dislike them, but I do think they have a right to be presented. Art says things that mirror our society, that make us think and argue. We cannot just break the mirror, because then we will not see ourselves or others.

How would you describe the relationship between art and activism?

If activism is being used in a magical way with imagination and creativity, it's art. And art also has more profound meanings if it struggles with human dignity or social justice. Then it has activism meaning in it. For me it's not separable.

In Human Flow, there are so many moments where you linger on an individual refugee in silence. It screamed, "Look at me! I'm human!" And the documentary as a whole felt the same way, an appeal not only to look, but also to see. What are you trying to make people feel when they watch the film?

We need to give a few more seconds than the news or media normally would to picture the people. They're human beings. When you look at them, you have to take a deep breath. You have to give the viewer a moment to digest what is in front of him or her. What I want to achieve in this film is to get people to pay attention to human suffering and to realize that the sufferer is part of our humanity and it hurts everybody. We do have a responsibility as someone who is more privileged. We should not give up the responsibility or turn our faces away. I put a challenge to everyone who watches it.

If anyone is being hurt anywhere in this world, we are all being hurt. This is a fundamental idea this film is trying to carry out. Yes, we have different religions, different backgrounds, different languages, but humanity as one, we're all vulnerable. We all want to have safety and for our children to have possibilities. We need to protect each other. Anyone may end up in a similar condition. People from the United States or in Europe, they are immigrants. They know exactly how difficult it is to give up a home, to go to another land to start over. How can we betray our own ideology and our own experience now to refuse people? To picture those people in such hard conditions as dangerous and to relate the name refugee to terrorist or a threat to society is extremely narrow-minded and cold. It will not help our society to become a healthy society.

How have we all failed—individuals, countries, the world—with regard to the refugee crisis?

If we really are conscious about this, about how it would affect our lives in generations, then the world leaders, the powerful nations, the decision-makers, have to sit down to find a solution to protect humanity and to [ensure] peace. But if we are not doing that—and we are still profiting from deals on either resources or arms—of course there will be big consequences and casualties. We always have to understand that these tragedies are really made by humans. They are created by humans and also can be solved by humans. That's why we had to make this film, for people to understand the situation and to act. Only enough individuals will make a political change.

Human Flow and Good Fences both address barriers that prevent tolerance. Trump built a campaign on ideas like implementing a travel ban targeting Muslims and building a wall to keep out Mexican immigrants. If you could speak to him, what would you say?

I think I would say, "Stop it." If he has any respect for American values. See how a great nation profits from accepting difference, from tolerance and understanding. Those things are really foundations of where this nation comes from. Trump's [grand]father was a German immigrant. To turn his power to limit people who are in need—all sorts of people who would contribute their knowledge and talents to this society—is not a way, like he campaigned, to make America great again. Building these walls is a ridiculous act. The emperor of China built the biggest, longest Great Wall. Now people only laugh about it, because it's tourist ruins. It doesn't defend anything, and it's a permanent [reminder] of the insulting of human dignity.