Two man-eating lions that terrorized railway workers in Tsavo, Kenya, more than a century ago did so because they had toothache, scientists have discovered. This is contrary to the popular theory that prey shortages had led them to start hunting humans, raising questions of whether lion attacks will happen more often in the future.

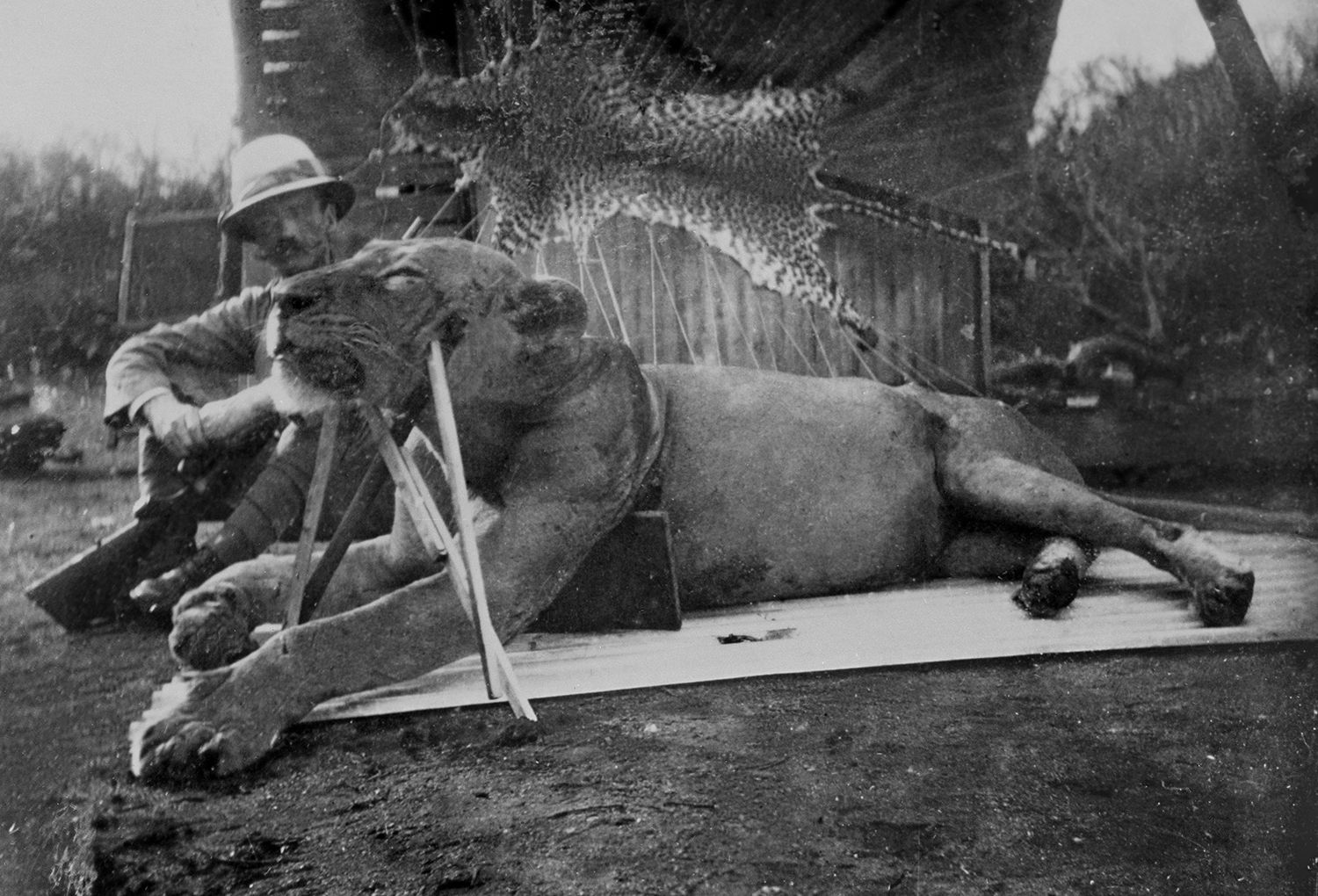

The two lions were shot and killed by Colonel John Henry Patterson in December of 1898. In his book about the events in Tsavo, he wrote: "I have a very vivid recollection of one particular night when the brutes seized a man from the railway station and brought him close to my camp to devour. I could plainly hear them crunching the bones, and the sound of their dreadful purring filled the air and rang in my ears for days afterwards."

The impact of the lion attacks was huge—delaying the construction of the Kenya-Uganda Railway to such an extent they were mentioned in British parliament. "The lions stopped the British Empire in its tracks at the height of its power," says Bruce Patterson, a co-author of the study published in Scientific Reports. "We humans like to think we're at the top of the food chain, but the moment we step off our paved streets, these other animals are really on top."

What led the two lions to start eating humans has been an ongoing debate —and understanding why could help authorities better protect both species where conflicts occur.

Scientists looked at the health of the two lions by examining their teeth for signs of food scarcity. They also looked at the teeth of another man-eating lion from Mfuwe, Zambia, which killed six people in 1991.

Using high-tech analysis, the researchers looked for microscopic signs of wear and tear in the days and weeks before the lions were killed. Before the Tsavo attacks, Kenya was in the middle of a two-year drought that had ravaged local wildlife. If the lions had been starving, their teeth would have shown signs of eating the bones of their prey—a behavior not normally seen when food is abundant. But there was virtually no wear and tear on the teeth, so much so they looked more like that of a captive lion.

In an email interview with Newsweek , lead author Larisa DeSantis said this finding was a big surprise, especially in light of the historic account by Patterson. "Because a rinderpest outbreak [an infectious viral disease that affects cattle] had also reduced prey populations, it was thought that prey shortages were to blame for the man-eating behavior," she says. "Further, it was thought that these lions only resorted to humans as a last resort—and thus were fully consuming prey and humans—including their bones."

Instead of showing signs of bone consumption, researchers found something very different. They found the lion that killed the majority of the 35 rail workers was suffering from severe dental disease and had root-tip abscess in one of its canines. This would have made normal hunting near impossible. Its partner had also suffered injuries to its teeth and jaw. The Mfuwe man-eater was found to have severe structural damage to its jaw.

"Tooth and/or dental damage in the first Tsavo lion and the Mfuwe man-eater is extreme and unlike the typically tooth damage that occurs in many lions," DeSantis said. "These injuries likely occurred while taking down prey and would have made hunting other large prey a risky and likely painful venture. Lions primarily subdue their prey with their jaws and with debilitating injuries to this area would have been less efficient hunters. Humans would have been a simple and fairly easy solution to their need for prey and much easier to subdue than a zebra, for example."

Researchers say the man-eaters appear to have shifted to "softer foods"—or humans—because they were no longer able to hunt their normal prey. Patterson says the findings suggest the causes driving man-eating behavior: "It's remarkably rare for lions to attack people, but it's catastrophic when it happens. When a big, dangerous predator becomes incapacitated, there's a real danger for this kind of behavior—no animal will let itself starve to death if there's another option."

While lions rarely attack humans now, DeSantis says this could change in the future. "Humans were likely an easy solution and were on the menu for these man-eaters," she says. "Humans have long been on the menu of large cats. Even our ancestors were prey—as inferred from anthropological evidence. In Tanzania, there were 563 humans killed by lions between January of 1990 and September of 2004. Also, three lions in India's Gir Forest were recently 'sentenced to captivity' after eating humans. While man-eating is rare, with increased human populations and declining prey, one might expect man-eating to become more common in the future."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Hannah Osborne is Nesweek's Science Editor, based in London, UK. Hannah joined Newsweek in 2017 from IBTimes UK. She is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.