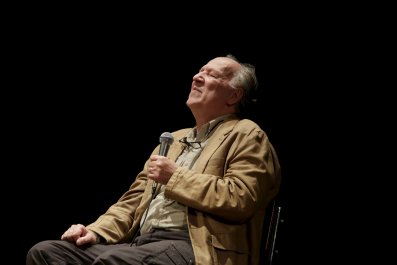

In mid-August, while on a trip to Europe, one of Turkey's most celebrated journalists was advised by his lawyers not to return to his homeland. The source of the perceived threat: his own government. "The signs were very clear," says the journalist, Can Dündar, who on August 16 resigned as editor of the independent newspaper Cumhuriyet. Dündar was sentenced in May to nearly six years in prison after being found guilty of revealing state secrets. His lawyers have appealed the verdict, but Dündar says the courts are a tool of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and no longer independent. "The prosecutor who arrested me is now the chief prosecutor in Istanbul," Dündar says, speaking by phone from his new home in a European city that he asks not be identified. "I am [at the] top of the list of journalists to be arrested [on further charges]. I could even face the death penalty." After Turkey's failed military coup on July 15, Erdogan voiced support for reintroducing capital punishment.

A rapidly growing number of Turkish journalists have taken refuge abroad, fearing they could be arrested and detained under laws that give security forces increased powers during Turkey's current state of emergency. Since the coup attempt, more than 40,000 people—academics, judges, journalists and state employees—have been detained in a wave o f politically oriented arrests so extensive that it has prompted the government to make space in Turkey's prisons by paroling 38,000 people imprisoned for crimes committed before July.

"The state of emergency will be used exclusively to bring the coup plotters to justice and prevent future attacks against our democracy," a senior government official tells Newsweek.

On July 28, Turkish authorities announced that they had closed down 131 media outlets with suspected links to Fethullah Gülen, a U.S.-based cleric whom Erdogan accused of plotting the coup. Many journalists who appear to have no link to Gülen have also been swept up.

After the attempted coup, several foreign journalists resigned from state-owned television channel TRT World. One, who asked to remain anonymous, says: "I left because it became clear that after the failed coup it was no longer possible to cover the story in Turkey objectively." (TRT World tells Newsweek that it continues "to relay the latest developments with all transparency to the world.")

The vast majority of people in Turkey are relieved that the coup failed. But critics of the government fear Erdogan will continue to use the foiled takeover as cover to suppress all sources of dissent." Erdogan used this military intervention as an excuse to build up his power," says Dündar. "What's the difference between a military coup and a police state? It's more or less the same for us."