When North Carolina doctors told expectant parents Heather and Jason Kroeger that their twin boys would be conjoined, they knew that, despite the high risk of death and the challenges such a birth would bring, they would keep the babies. The twins were born healthy at 5:20 a.m. on September 5. More than two weeks later, they are still healthy, defying steep odds.

Although the family has not publicly shared the exact anatomy of the twins, it is likely that each individual has their own spine, and possibly some of their own organs. But they will remain attached. Because of their unique anatomy, it would be impossible to separate the twins while preserving their quality of life.

Although they are currently healthy, the twins face health issues. In fact, when doctors noticed that Heather's twins were conjoined in utero, they suggested an abortion. "To us, it wasn't an option," Jason told Fox19.

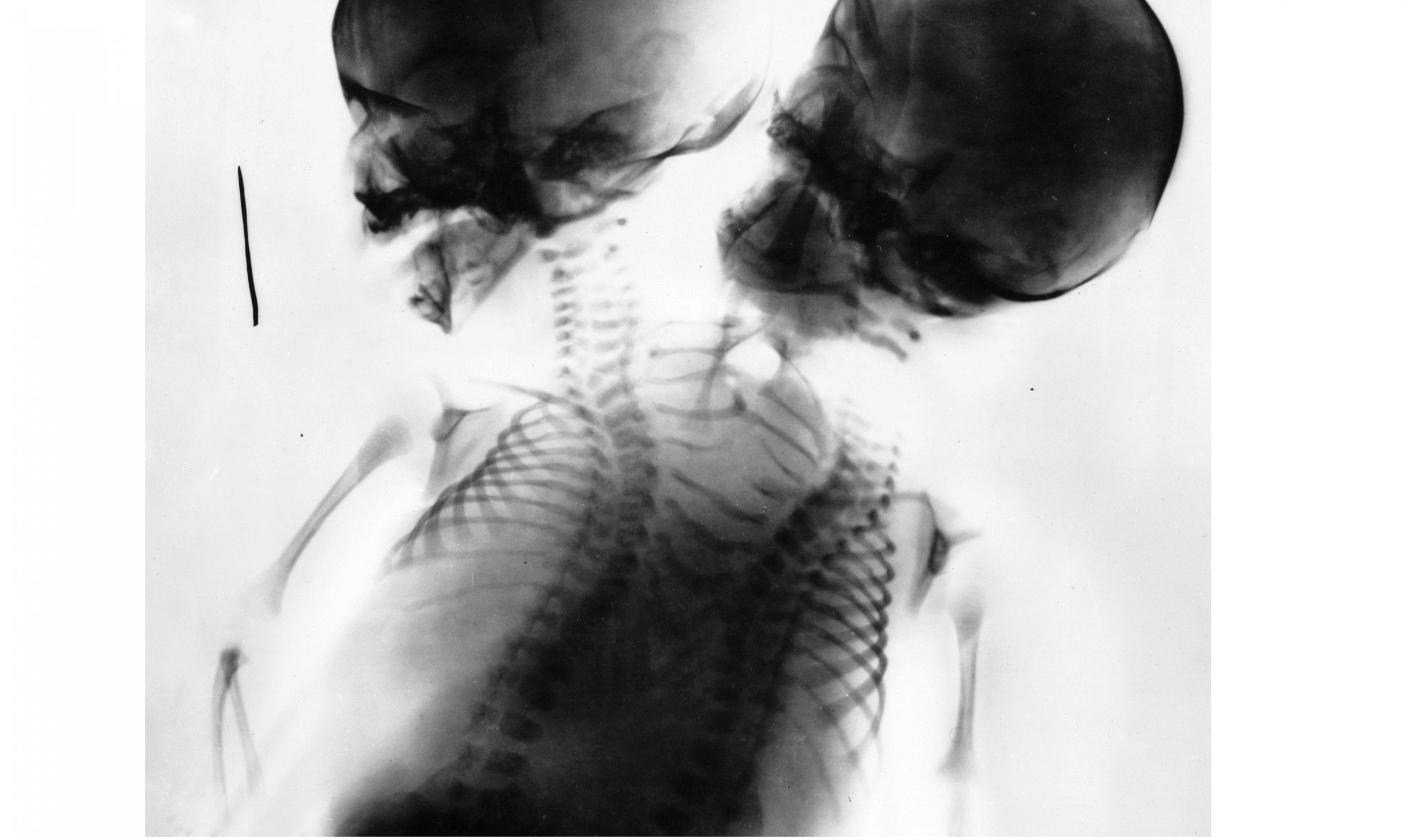

Elijah and Isaac are "parapagus dicephalus" twins, meaning "joined at the bottom, two heads." Like other conjoined twins, they may have formed when one embryo began splitting but did not completely do so, or when two embryos nearly—but not entirely—merged into one. In all cases of conjoined twins, the twins are identical. According to research published in the American Journal of Medical Genetics, female babies and babies born in South Asian countries are more likely to be born conjoined, but no genetic or environmental factors that make conjoined twinning more likely have been identified.

Conjoined twinning is often fatal: about half of conjoined twins are born dead, and another 35 percent of those born alive die within 24 hours. However, doctors can separate some sets of twins with less severe conjoining, such as Jadon and Anias McDonald, who were born attached at their heads. They underwent a successful surgery at 13 months old and celebrated their second birthdays earlier this month.

Lewis Spitz, a pediatric surgeon at University College, London, and an expert in conjoined twins, says that there is no one-size-fits-all treatment for conjoined twins. "Each one is different, there's no doubt about that. Even if they're joined at the same area, they're all different. One has to be very aware of the difference, because it can affect how separation takes place," Spitz tells Newsweek.

All sets of conjoined twins are very different, but Spitz, who has written about the ethics of managing such births, has identified three approaches to treatment based on prognoses. Sometimes separation is not possible at all. Other times, a surgical separation must be performed in the emergency room. And some sets of attached twins are healthy enough for a planned separation operation. In his study, 40 percent of conjoined individuals survived an emergency operation (nine people from 11 twin sets). By contrast, 91 percent of people survived planned procedures (33 individuals from 18 twin sets).

Occasionally, conjoined twins simply have to stay together. For instance, Brittany and Abby Hansel are famous conjoined twins who were born in 1990. Like Elijah and Isaac, they each have their own head, but are joined at the torso and below. Brittany and Abby have two spines, two hearts, three lungs, one liver, and two stomachs. They each have their own personality, with individual driver's licenses and college degrees. Abby and Brittany can each control one side of the body, and have to coordinate their efforts when walking or swimming.

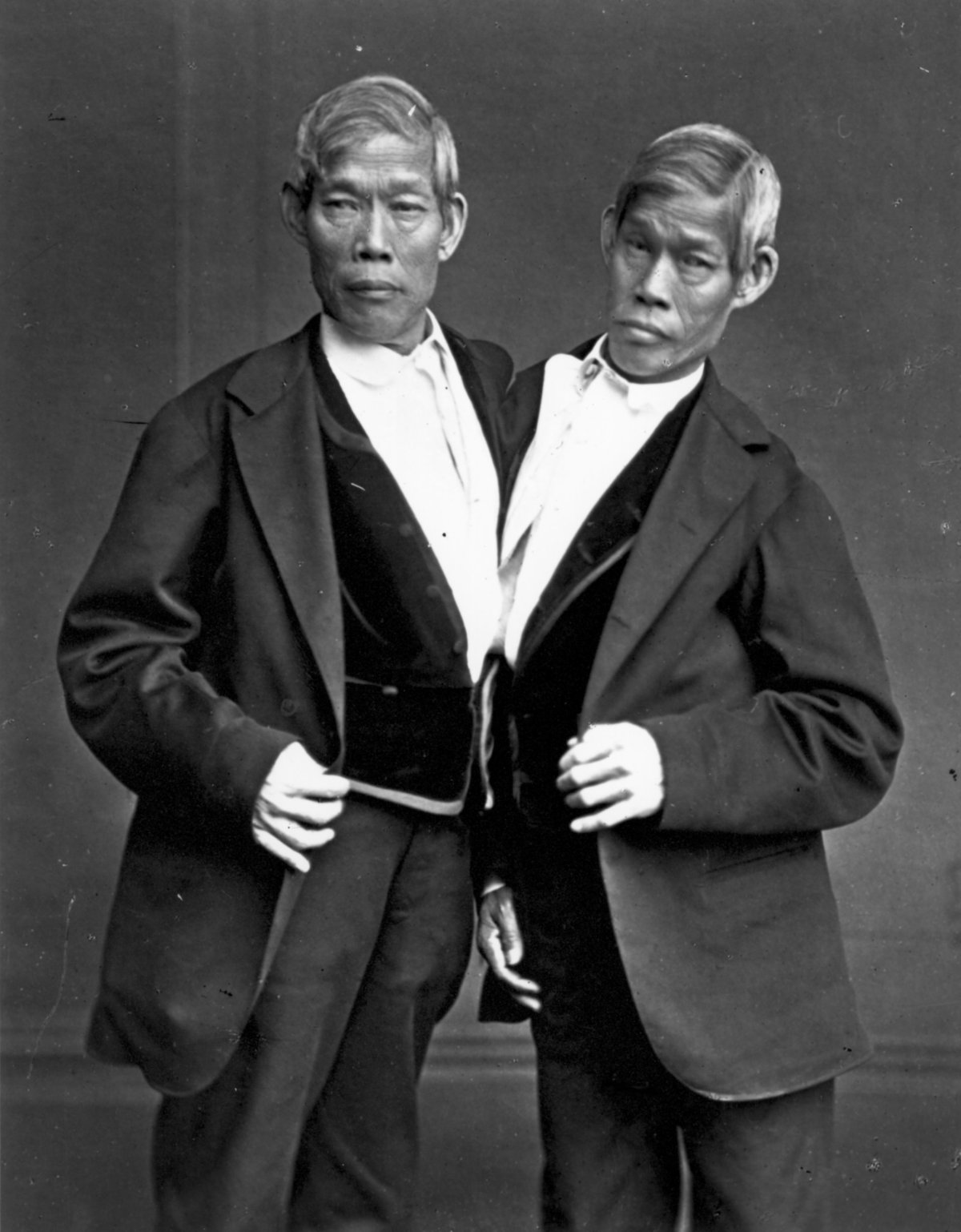

Chang and Eng Bunker, another famous pair of conjoined twins, were attached at the liver and toured the U.S. with circuses. They lived for 63 years—longer than any other set of conjoined twins. Chang and Eng were born in The Kingdom of Siam (now Thailand) and inspired the now-outdated term "Siamese Twins."

When the Kroegers found out that the fetuses were attached, doctors at their local North Carolina hospital advised them to deliver the babies at a larger hospital equipped with more staff to handle the high-risk scenario. Family and friends donated money for the trip to Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, where Heather delivered the boys.

Laura Streittman, a friend of the Kroeger's, started a GoFundMe page to help cover expenses related to travel and pre- and post-natal care. According to Streittman's update, the boys are doing "[s]o much better than ever expected." They are grinning, acting alert, looking in the direction of voices, and crying, according to Streittman.

Neither the family nor the hospital wanted to comment on this case, citing privacy, but the Kroegers released a statement saying that they were grateful for the support and prayers, and they are focusing on trying to bring the twins home.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kristin is a science journalist in New York who has lived in DC, Boston, LA, and the SF Bay Area. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.