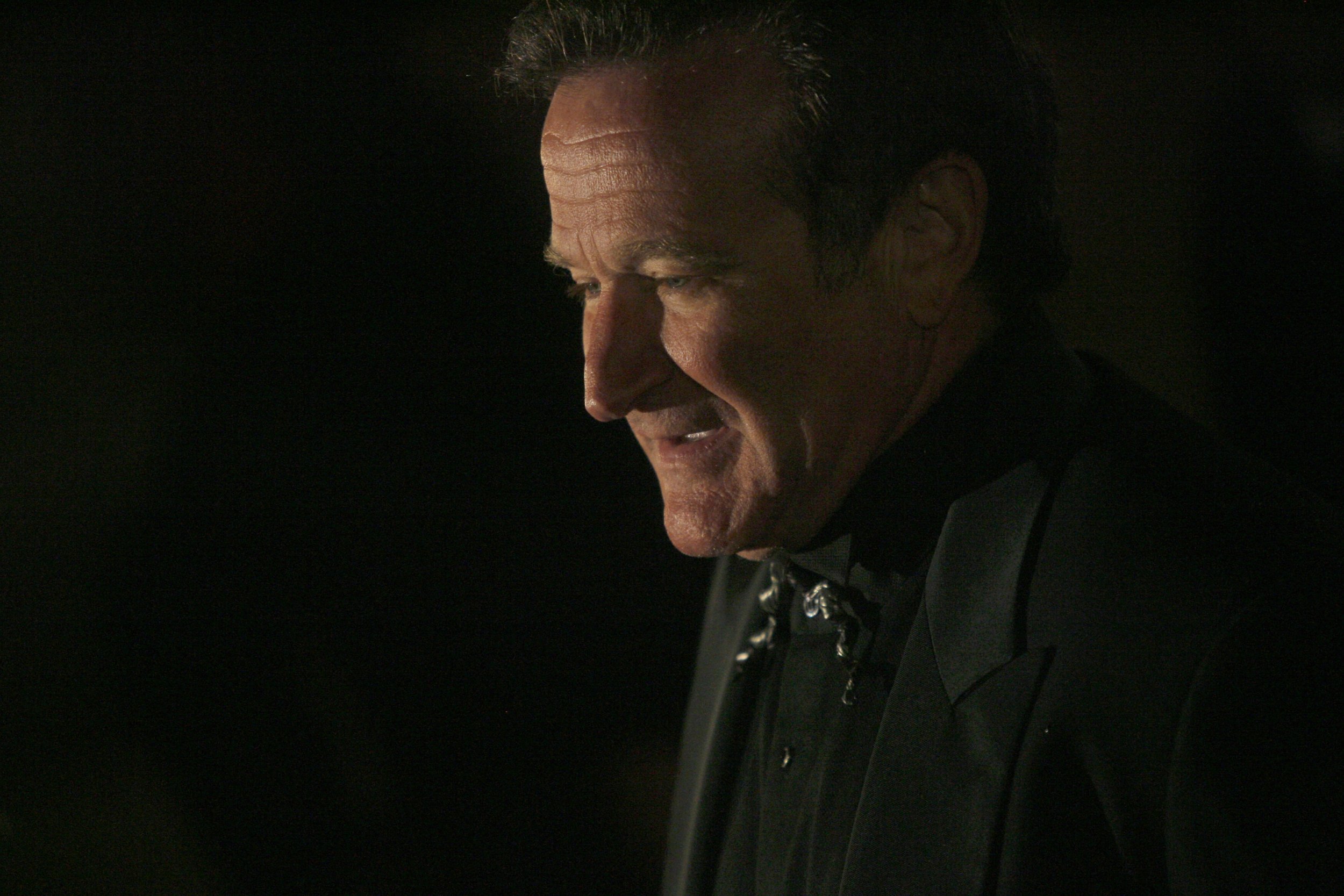

Updated | A full two months after Robin Williams' death from suicide on August 11, a scattered handful of mental health professionals and volunteers are still feeling the aftereffects. They are suicide prevention hotline directors and operators, spread across the country but allied in their commitment to meeting the demand for mental health services that routinely spikes after a celebrity or public figure takes their own life.

This particular spike, though—in size as well as duration—is all but unprecedented, says John Draper, a psychologist who serves as director of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (NSPL).

"One could say that there have not been any media reports of a celebrity of this magnitude, with this kind of public profile, whose death was exclusively attributed to suicide," Draper told Newsweek. "We haven't seen that in at least 20 years if not longer." In 1994, most notably, Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain's suicide flooded crisis hotlines with a steep rise in calls; just the previous year, experts had issued media guidelines emphasizing the need to include suicide-prevention resources when reporting on high-profile cases.

But that was eleven years before the NSPL, which today entails a 24-hour network of more than 160 crisis centers, was launched. Since then, Draper says, the daily volume of calls has regularly spiked at times of tragedy (Hurricane Katrina was a big one) and when cable news programs broadcast the number (it's 1-800-273-TALK). But never to this extent.

On August 12, the day after Williams's death, calls to the Lifeline more than doubled from a typical 3,500 a day to about 7,400. "In some ways, it was kind of a tsunami of calls," Draper said. The remainder of August saw 700–800 more calls per day than normal, while that spike dipped to 400 in September. Today, the Lifeline is still receiving 200 more calls a day than is standard, Draper says.

Local crisis centers have reported similar rises, albeit on a smaller scale. In New York, for instance, the Crisis Services hotline in Buffalo received 355 calls in August and 313 calls in September compared with a prior average of 244 calls per month in 2014. The Long Island Crisis Center, meanwhile, has received 324 suicide-related calls in the two months since Williams' death—a 34 percent rise from the 242 calls it received in the two months prior. "We're attributing that to heightened awareness," said Linda Leonard, executive director of the Center.

Though that seems like ample cause for concern (any highly publicized suicide sparks fears of a copycat effect), experts take a more optimistic view: hundreds more at-risk callers, they say, are reaching out and receiving the professional support they would otherwise go without.

"Because of the way in which the media responded to this event, at least in terms of getting the [hotline] number out, about 30,000 callers who might not have gotten help are getting help," Draper estimated. In Leonard's view, "As much as a tragedy that this was, it allowed people to see that it's okay to reach out for help. There's been tremendous publicity about it. It just takes that edge off of the stigma."

Mental health professionals have seen this sort of phenomenon before, though not since the advent of online media. When Kurt Cobain died, experts feared an epidemic of copycat cases; that's more or less what happened after Marilyn Monroe's death three decades prior. But the opposite trend emerged. According to research by clinical psychologist David Jobes, the suicide rate in Cobain's home of Seattle—as well as in faraway locales like Australia, where Nirvana had a large following—decreased following the singer's death.

That's largely attributed to the work of mental health outreach and responsible media practices. The result is that Cobain's death, though tragic and avoidable, may have somehow saved lives. Could Robin Williams' demise have done the same?

Because the country's surveillance system for suicide trails by two to three years, that data won't be available for some time, says Dr. Christine Moutier, who is Chief Medical Officer at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. But the rise in calls is a strong indicator.

"It's possible that some vulnerable people were triggered to feel more distressed as well," Moutier speculated in an email to Newsweek. "But when help seeking increases, it is usually thought to be a very positive sign of people who would otherwise have been suffering in silence reaching out for help."

"The more the media talks about the effectiveness and impact of suicide prevention as opposed to the impact of suicide itself, the more likely people are to get and seek help," Draper added. "The story of hope has got to get out there."

Correction: This article originally misstated the name of the organization as the National Suicide Prevention Hotline. It is the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

Note: The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached at 1-800-273-8255. Suicide warning signs are listed here.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Zach Schonfeld is a senior writer for Newsweek, where he covers culture for the print magazine. Previously, he was an ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.