The war in Ukraine has reached its one-year anniversary. I know the significance of this milestone because 30 years ago, I lived through a nearly four-year siege as a child in Sarajevo, Bosnia during the Bosnian War.

I also know the silent dread of entering yet another year likely to be claimed by war.

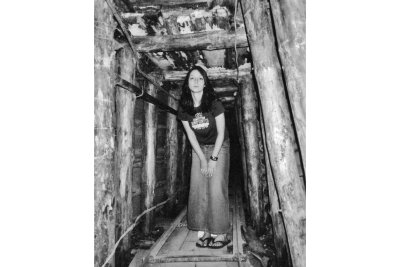

The first year of the Siege of Sarajevo began on April 5, 1992, and was pockmarked with pain, fear and loss: I was wounded by a mortar shell that hit our apartment building. My father lost his job when the company he worked for ceased to exist. My mother insisted on walking to work amid shelling and sniper fire. Both of our cars were destroyed by explosions. My brother and I could not go to school because my middle school was targeted by mortar shells and his university was in enemy territory. So too was our cottage just outside of the city—a property into which my parents poured most of their savings.

All this left us reeling, but we had no time to absorb any of it, because we were too busy surviving the relentless onslaught of shelling, and the deprivation that so often comes with war.

Most days, we lacked electricity and running water, and we depended on humanitarian aid. It usually consisted of flour, rice and lentils with an occasional can of meat. Fruits and vegetables were scarce and I often caught myself daydreaming of the plump raspberries we used to grow at the cottage. Although we were never starving, I felt a small, hollow ache in my stomach after every meal—a longing for the variety we had before the siege. Eventually, my brother got a job with the United Nations (UN) and started feeding our family with the leftovers from the UN soldiers, often making an effort to surprise me with an orange or some chocolate.

While my brother's efforts staved off hunger, the sense of scarcity permeated every other aspect of our lives under siege. Whenever we were out of toothpaste, my mother would cut the tube open lengthwise and at the bottom seam so that it splayed out like a gutted fish. We scraped off the dried streaks of paste until the lining began to peel, leaving silvery flakes on the bristles of our toothbrushes and a faint smell of mint.

The city was shelled on a daily basis and every time my mother went to work or my father went out in search of water, I held my breath until they returned. Twitching in anticipation, I wondered if they were still alive. I felt like a marionette in the hands of a deranged puppeteer, my nerves snapping from taut to slack, taut to slack. They seized with fear at the sound of an explosion, then slumped during the brief lull before the next one.

My best friend left the country without saying goodbye—her parents scrambled to send her abroad just before the siege. I mourned her absence, especially since I could look out of my bedroom window and see her apartment across the courtyard in a neighboring building. On the rare occasion she called from Germany, I was abuzz with excitement just to hear her voice, but our lack of common experience made our conversations stilted. There was so much we wanted to share, but now it was as if we spoke different languages. Hanging up the phone, I felt a confused mixture of sadness and relief.

In the first months of the war, we could say: "This will soon pass. Just a few more months and we will have peace." We said it to each other, but more often to ourselves. The incessant shelling and our daily privations said otherwise, but we gained some comfort from picking a date a few months into the future—usually a birthday or a holiday—which we hoped to celebrate in peace. The imagined date was a shiny milepost far down the jagged trail we were yet to navigate, but we tethered ourselves to it and hoped to reach it.

But as birthdays and holidays went by, the war seemed no closer to its end. Hoping became painful and we no longer uttered words like: "Just a few more months and we will have peace." They felt hollow, offensive even.

By then, most of the trees had been cut down for firewood and our neighborhood looked grim and bare. The few fruit trees that were left bore fruit which rotted on the branches, because it was too dangerous to go outside and pick them.

People had to bury their loved ones in the nearby parks and in the courtyards of their apartment buildings, because the shelling was too intense to make it to the cemetery. By mid-fall of 1992, the Sarajevo city zoo had turned into a graveyard of carcasses as all of the animals died of hunger. When I read about its last inhabitant— a brown bear who had wasted away—I cried for every loss and for every withered hope.

On this one-year anniversary of the war in Ukraine, I think of a recent David Letterman interview with Ukraine's president Volodymyr Zelensky. When asked what he was looking forward to after the war, Zelensky simply said: "I would really like to just go to the sea."

As he squinted his eyes into a boyish smile, I recognized his expression as that of my own during the siege. I too had longed to go to the sea. In the grimmest months of winter, without heat or electricity, I warmed myself with memories of our family vacations on the Adriatic coast. I secretly indulged in a fantasy of lying in the sun until the scars on my legs completely disappeared.

Almost 30 years ago in Bosnia, aged 13, I stepped over the threshold of the first full year of the siege along with my fellow Sarajevans. We did it without ceremony, because we were too busy surviving. That day, I wrote in my diary: "The days of the war pass, each like the last. There is no electricity, no water, no firewood, no bread, no food, no friends..."

What I did not write about, and what most of us dared not verbalize just yet, was the dread we felt while staring at the cold fact that the war had plucked a whole year of our lives and drenched it in loss.

Worse still was the worry that the world was already looking away and that we would be forgotten. I remember thinking: "If the war took one year, it could easily take another, and another after that." I used all my hope to resist such thoughts, but it would be nearly four years before any of us saw peace.

In the past year, from where I now live in Canada, I have watched as the Ukrainian people have shown the same courage and resilience that Sarajevans demonstrated some three decades earlier. As the war enters its second year, I trust that their formidable spirit will withstand whatever comes their way.

I hope President Zelensky, and the Ukrainians who share in his wish, will soon get to go to the sea. Above all, I hope that the children of Ukraine—and millions of others in parts of the world where war has been raging on for years—will return to school and their childhood games, with whatever remains of their innocence.

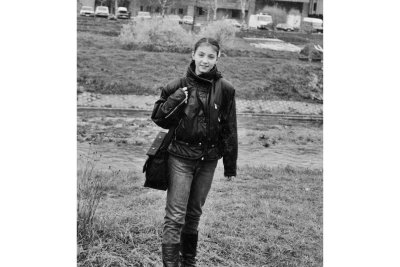

Nadja Halilbegovich is the author of My Childhood Under Fire: A Sarajevo Diary, as well as numerous essays for publications such as Time, The Atlantic, The Boston Globe and The Globe and Mail. You can find out more at nadjapeace.com.

All views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.