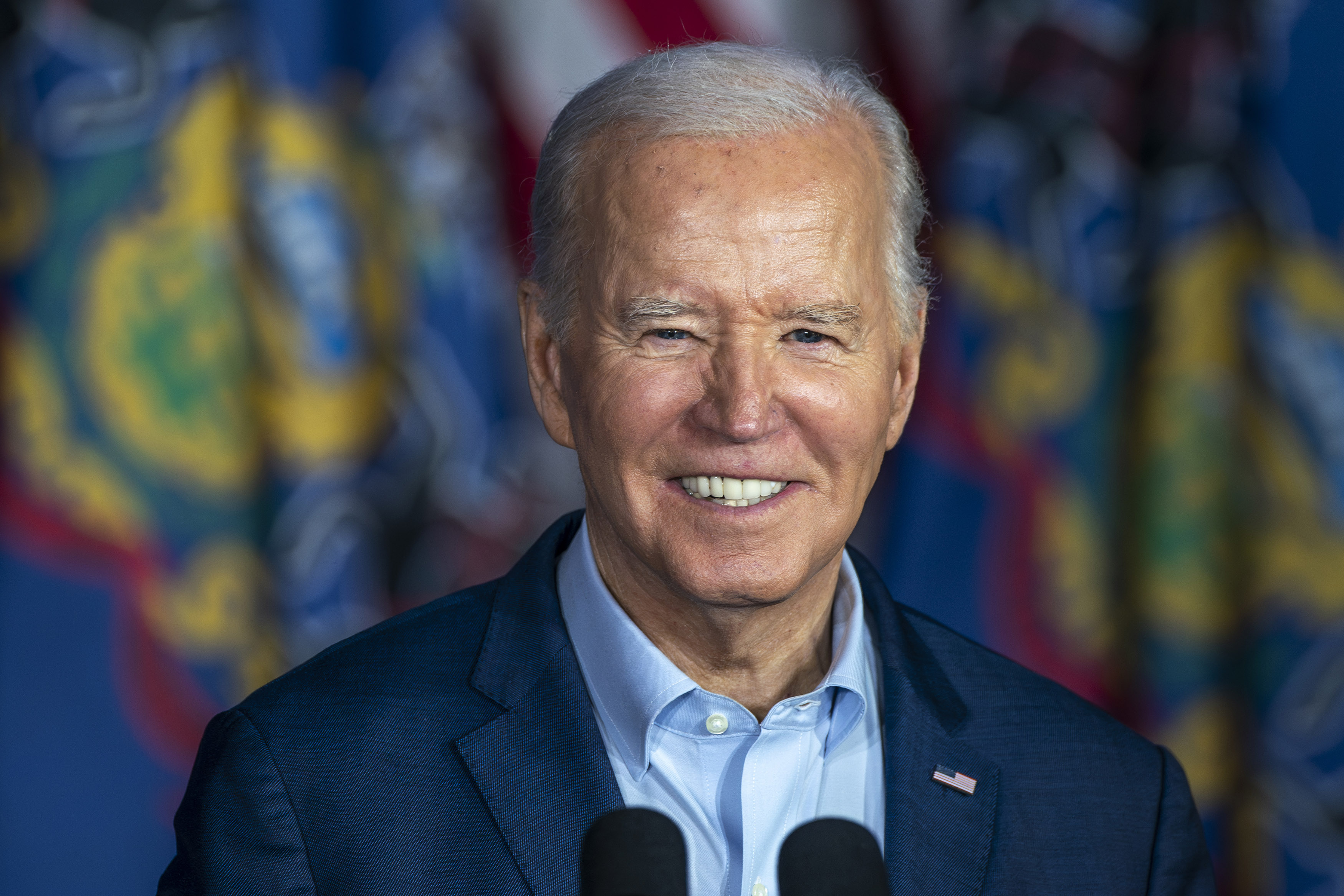

The U.N. Security Council, the organization's most important body on matters of peace and international security, could use a heavy dose of reform. International politics have changed markedly since the Council's first session in January 1946; states that were minor players in the international system at that time, like India and Brazil, are now significant powers in their respective regions. Going back to 1990, U.S. presidents have advocated for enlarging the Security Council: Bill Clinton wanted to grant Japan and Germany permanent seats; George W. Bush wanted Japan to join; and Barack Obama put his support for India's membership in writing. President Joe Biden has picked up on the tradition, tasking his ambassador to the U.N., Linda Thomas-Greenfield, to lead an initiative that would add six permanent seats to the chamber (albeit without veto power).

The last three U.N. secretary-generals have not only echoed those calls but pegged changing the composition of the Security Council as a critical test of the U.N. system's ability to adapt to evolving circumstances. Kofi Annan said in 2006 that "so long as the Council remains unreformed, the whole process of transforming governance in other parts of the system is handicapped by the perception of an inequitable distribution of power." Ban Ki-moon, Annan's successor, made a similar point in 2015, arguing that the Security Council should become more democratic, transparent, and accountable. The current secretary general, António Guterres, is no different.

Wants and desires, however, don't mean much in the realm of great power politics. They mean even less in the gargantuan U.N. bureaucracy, governed by rules and regulations deliberately designed to ensure consensus on major issues that would impact its member states and the organization writ-large. And therein lies the big problem for reform advocates: The U.N.'s founding charter makes it practically impossible to achieve the change they're seeking.

Enlarging the Security Council requires amending the U.N. charter. But the amendment process, spelled out toward the end of the charter in Articles 108 and 109, is laborious. Two-thirds of the General Assembly and 9 out of 15 members of the Security Council must vote in the affirmative just to call a conference and review proposed changes to the charter. If the conference by a two-thirds vote recommends potential changes, two-thirds of the General Assembly and all five permanent members of the Security Council (the U.S., U.K., France, Russia, and China, known as the Permanent Five or P5) must approve and ratify them through their domestic constitutional processes. Ratification would be a mind-numbingly complex affair that could drag out in perpetuity; a group of U.N. member states coming together to hold up the process as a way to extract unrelated concessions from the organization is a very real possibility. Given the torturous proceedings, it's no wonder why the U.N. charter hasn't been modified since 1973.

Ultimately, however, the entire amendment process is at the mercy of the P5. Any one of them could single-handedly kill enlargement, or any amendment to the charter, by utilizing its veto power. In other words: The only way Security Council enlargement or other reform will happen is if all the permanent members believe it's in their best interest to support it.

This is where it gets tricky. Whether enlargement is in the interest of a permanent member depends, in large part, on which candidate is being considered for a promotion. This means there is no one-size-fits-all formula that could break the logjam that will inevitably arise during discussions. China, for example, is highly unlikely to support a permanent seat for Japan or India at a time when Beijing's relations with both are increasingly adversarial. Russia is unlikely to accede to any candidate sponsored by the U.S., U.K., or France, if only to frustrate Western ambitions and demonstrate to Washington and its European allies that Moscow still needs to be courted.

While the P5 wouldn't dispute the notion that Africa deserves much more recognition in the Security Council, African governments disagree among themselves on which state to nominate. The same can be said about the Western Hemisphere; Brazil is an obvious candidate due to its population, the largest in Latin America, and the size of its gross domestic product ($1.9 trillion). But don't other states, like Mexico, deserve consideration as well?

There's also the question of whether making the Security Council tent bigger would do anything to alleviate its divisions. Chances are it wouldn't.

Russia and China would still have vetoes in their pockets and wouldn't hesitate to brandish them. Neither would Washington. Russia would continue quashing pro-Ukraine resolutions and statements through the U.N. China would continue to lock out the Taiwan issue from Security Council's deliberations. Debates would be longer, quick action would be less likely, and draft resolutions would have to account for even more viewpoints—some of which may be irreconcilable—than they already do. This wouldn't be exclusive to the Security Council; the larger any organization is, the harder it is to arrive at an agreement. Just ask NATO—a defense treaty of 31 member states still waiting for Turkey and Hungary to formally approve Sweden's membership more than a year after it submitted its application. In general, the more players at the table, the longer and potentially more complicated the game will be. The national interest will continue to dominate.

A lot of things sound good in theory, only to run into a dead-end in practice. Count Security Council enlargement as one of them.

Daniel R. DePetris is a fellow at Defense Priorities and a syndicated foreign affairs columnist at the Chicago Tribune.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.