On the same day the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed measles cases are at their highest since the virus was declared eliminated in 2000, UNICEF announced that 21.1 million children had missed their first dose of the measles vaccine every year over the last eight years.

Between 2010 and 2017, UNICEF estimated 169 million children did not have their first dose of the vaccine, amounting to 21.1 million children annually on average. In order for the vaccine to work, two doses of the vaccine are "essential," the United Nations body stated.

Worldwide cases of the virus in the first three months of 2019 spiked by nearly 300 percent compared with the same period last year. Children made up most of the 110,000 people estimated to have died of the virus in 2017, with the number of deaths up 22 percent from 2016.

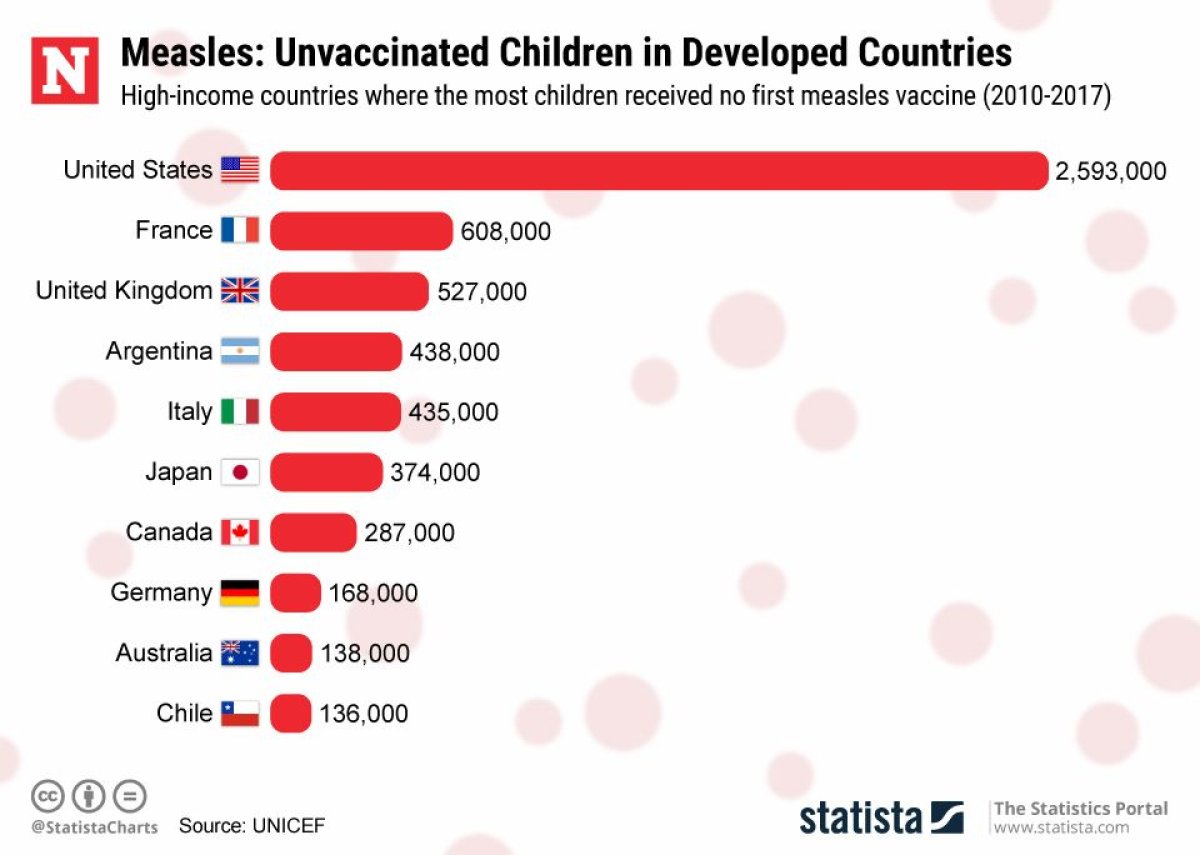

The U.S. topped a list of high-income countries where children were not treated with the first measles vaccine dose between 2010 to 2017, at 2,593,000 cases. It was followed by France at 608,000 and the U.K. with 527,000.

The graphic below, provided by Statista, illustrates the number of children not vaccinated for measles in the U.S. compared to other developed countries.

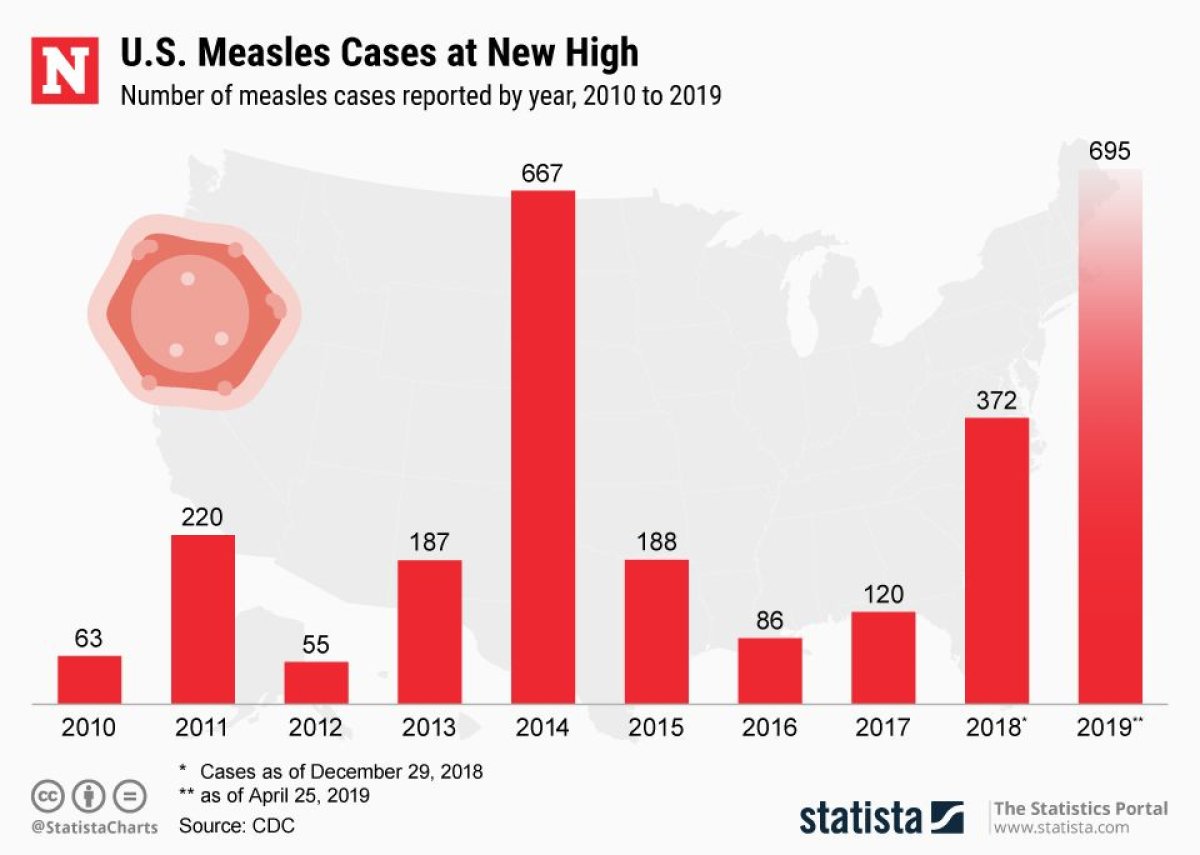

On Thursday, the CDC also confirmed some 695 measles cases have been identified across 22 U.S. states, mainly concentrated in one outbreak in Washington state and two in New York state.

The graphic below, provided by Statista, illustrates the number of reported measles cases in the U.S. since 2010.

A combination of factors has led to the spike in measles cases according to UNICEF, including complacency among parents and "fear or skepticism about vaccines." The swell of anti-vaccine sentiment is widely dubbed the "anti-vaxxer movement," which uses social media to spread misinformation about shots. A lack of access to health care is also an issue in many countries, UNICEF said.

The CDC stated on Thursday: "A significant factor contributing to the outbreaks in New York is misinformation in the communities about the safety of the measles/mumps/rubella vaccine. Some organizations are deliberately targeting these communities with inaccurate and misleading information about vaccines."

Henrietta Fore, executive director of UNICEF, commented: "The ground for the global measles outbreaks we are witnessing today was laid years ago.

"The measles virus will always find unvaccinated children. If we are serious about averting the spread of this dangerous but preventable disease, we need to vaccinate every child, in rich and poor countries alike."

The measles vaccine works thanks to herd immunity, in which a population is protected from an infectious disease because the vast majority of people have been vaccinated against it. That not only means an individual won't fall ill themselves, but is also less likely to pass it to the most vulnerable who can't receive vaccines because their immune system is too weak. Newborn babies and children with cancer fall into this category.

However, for herd immunity to work for the measles vaccine, 95 percent of the population must have up-to-date shots.

According to UNICEF, the global coverage for the first dose of the vaccine was 85 percent in 2017, dropping to 67 percent for the second does. The level of coverage can vary from country to country, and community to community. In high-income countries coverage with the first dose is 94 percent, falling to 91 percent for the second.

For instance, between 2017 and 2018, only 77.6 percent of children from kindergarten to 12th grade in Clark County, Washington—which has been hit by a measles outbreak—received all their shots.

The CDC urged parents to speak to their family health care provider about the importance of vaccinations.

Professor Jennifer Reich from the Sociology Department at the University of Colorado Denver, author of Calling the Shots: Why Parents Reject Vaccines, told Newsweek: "For many, measles is not a significant disease, but for others it is life-threatening or can lead to lifelong health issues. The problem is that we can't know whose children will be the most affected, which makes it important to take the risk seriously. When I talk to parents who choose not to vaccinate their children, they often assume because their children and healthy or they have good nutrition their children won't be the ones who experience the worst outcomes. This is a mistake.

"Unlike other diseases, measles does not require direct contact with an infected person and as a result is incredibly contagious. In my research, parents who reject vaccines often tell me how they work hard to anticipate who their kids interact with or where they go to avoid risks of infection. For parents who think they can protect their children from infection without vaccination, this disease is particularly challenging."

Professor William Moss, a specialist in epidemiology and immunology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told Newsweek: "The rise of measles is very worrisome for several reasons. First, measles is a serious disease that can kill or lead to life-long disability.

"Second, the rise of measles is a clear sign that we are not providing children with the life-saving vaccines they need. Measles outbreaks are the best evidence we have that vaccine coverage is low. Third, these outbreaks show that we have neglected measles as a public health priority. We lost our way and this is a wake-up call to stop a serious disease that is preventable."

Both Reich and Moss stressed the measles vaccine is safe and effective.

This article was updated to include infographics, and with comment from Professor Jennifer Reich and Professor William Moss.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kashmira Gander is Deputy Science Editor at Newsweek. Her interests include health, gender, LGBTQIA+ issues, human rights, subcultures, music, and lifestyle. Her ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.