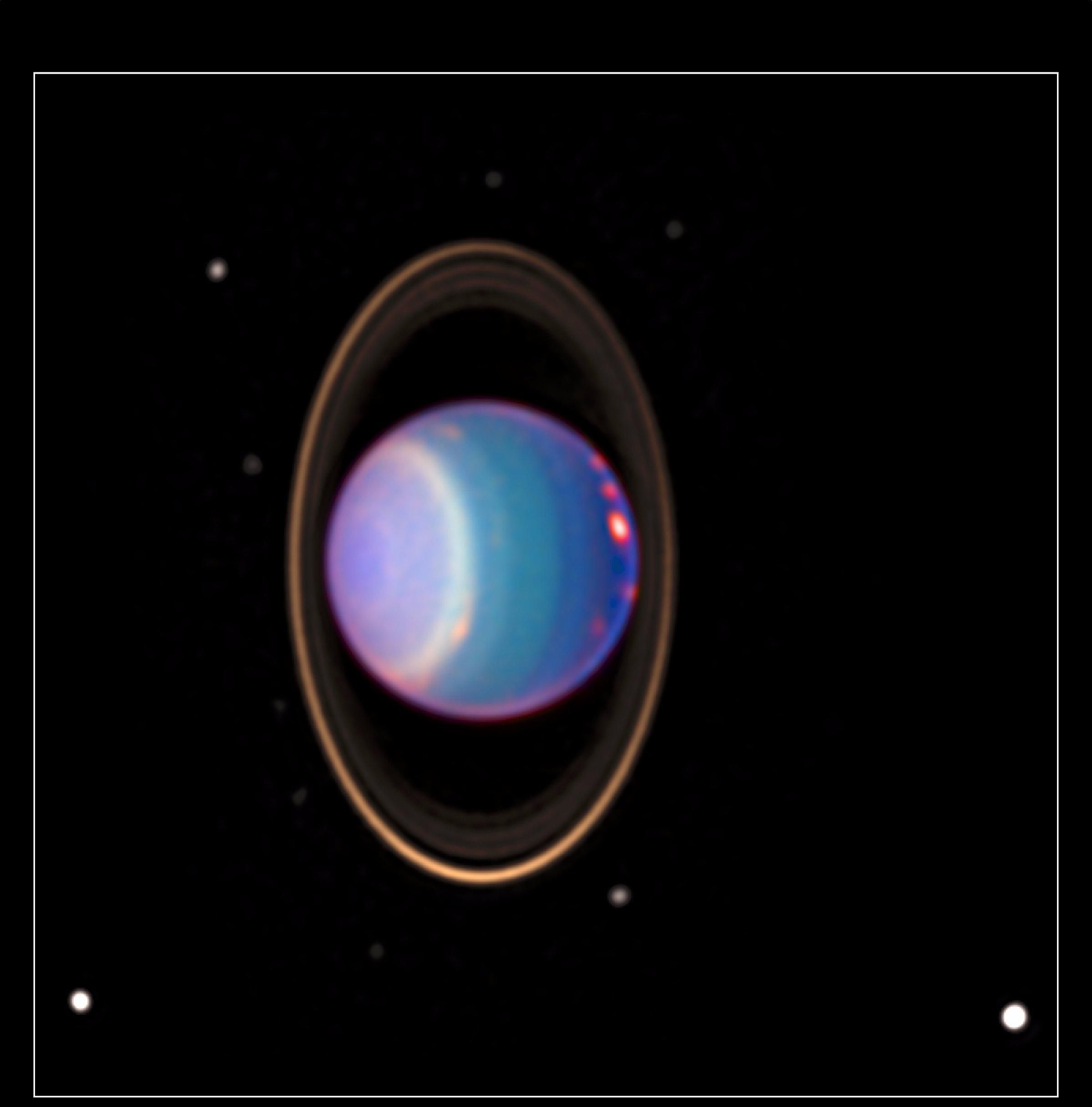

If ever there were a planet that looked drunk, Uranus is it: the blueish-tinged planet spins on its side, like it has toppled over after a long night. And research presented last week at the annual conference of the American Geophysical Union and reported by Space.com suggests that the drunken spin may share origins with many of the planet's moons. This whole situation may be the result of a very rough encounter deep in the planet's history.

The new research looks to explain Uranus's unusual axial tilt, the angle at which a planet spins in relationship to its path around the sun. Most of the planets in our solar system spin more or less upright, like Venus's tiny three-degree tilt. Earth is slightly more tilted, by about 23 degrees—like walking against a stiff gust of wind—which is what gives us seasons.

But Uranus is tilted by about 98 degrees, which means it's essentially laying on its side as it orbits. (A charming side effect of that tilt is that a winter at one of the planet's poles lasts 21 years—and you thought four months was rough.)

Scientists aren't quite sure what precisely caused Uranus's weird tilt. Some believe it could have slipped over on its side as it wandered around during the early days of planets. But other scientists have been suspicious that the planet was hit by some giant space thing—it would have had to have been about the size of Earth today—and that the impact knocked Uranus askew.

The new research builds on that idea by running models to see whether a giant collision like that could solve two planet-sized problems: accounting for both Uranus's tilt and the creation of all of its large moons.

Uranus's moons come in two categories. Nine are pretty puny and have unusual orbits, so scientists think the planet's huge gravity captured them as they flew by. But the other 18, which are larger and more orderly, haven't quite been explained yet either, and that's where the new research looks to blame a huge collision.

The scientists behind the project designed computer models of Uranus and found that if you hit the early planet with a hunk of rock the size of Earth, you can both skew the planet and create enough debris that you get a system of moons pretty similar to what we see around the planet today.

And that's not so strange a story either if we look closer to home: our own Moon also likely formed when something huge rammed into Earth and sent debris flying out into orbit.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Meghan Bartels is a science journalist based in New York City who covers the science happening on the surface of ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.