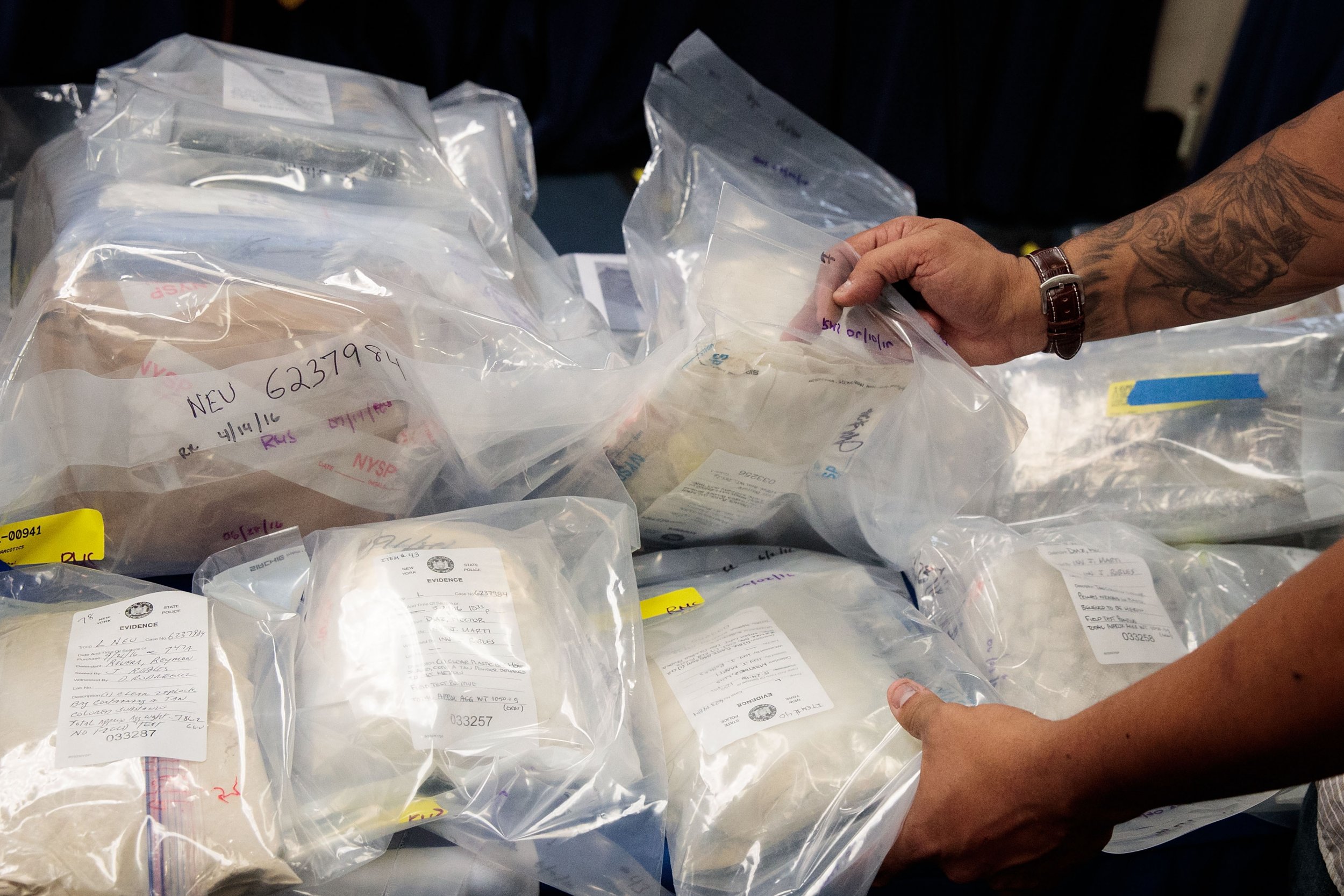

The U.S. is in the middle of a heroin epidemic. In 2016, the U.N. Office of Drugs and Crime published a report that estimated that heroin consumption in the U.S. had increased by 145 percent between 2007 and 2014. The U.N. was not alone in its grim findings. In 2015, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recorded 12,989 heroin-related deaths in the U.S.

The vast majority of the U.S. heroin supply pours in from its southern border. Mexico provides the greatest amount of the drug, with Colombia exporting the second-most amount.

In his election campaign, Donald Trump promised that he would get tough on drugs—specifically mentioning trafficking from Mexico. His Twitter page alone makes clear his stance on the issue, as he conflates the drug trade with issues of immigration and national security.

Heroin overdoses are taking over our children and others in the MIDWEST. Coming in from our southern border. We need strong border & WALL!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 27, 2016

One of my first acts as President will be to deport the drug lords and then secure the border. #Debate #MAGA

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 20, 2016

On February 9, Trump signed an anti-trafficking executive order that employed similarly emotive language. Transnational criminal organizations, the document reads, are "threatening the safety of the United States and its citizens" and have "triggered a resurgence in deadly drug abuse."

But despite the fiery rhetoric, the order only implements a vague policy of "increased security sector assistance to," and intelligence sharing with, foreign partners.

Read more: Obama drug czar asks: Where's Donald Trump's opioid crisis plan?

We know that Trump's administration wants to crack down on drugs. In January, his Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, refused to condemn President Rodrigo Duterte's homicidal drug war in the Philippines. His vice-president, the former governor of Indiana Mike Pence, promised his state back in 2013 that he would "stay tough on narcotics." Trump's Attorney-General, Jeff Sessions, has claimed that "good people don't smoke marijuana."

Since the 1970s, U.S. drugs policy has focused on cutting off the supply of narcotics at the source through the forced eradication of drug crops (including opium, coca and marijuana), interception of drugs in transit and the disruption of trafficking organizations. The U.S. has put pressure on many source and transit countries to use such methods in order to produce quick results, measuring their success in terms of acres eradicated, drug labs destroyed or traffickers arrested.

Stopping the supply of drugs at source is difficult, costly and requires long-term strategies. It is, however, achievable and need not cause great harm to farming communities. Poorly planned interventions in the drugs trade can cause an increase in the supply rather than stopping it. In my recent book, Suppressing Illicit Opium Production: Successful Intervention in Asia and the Middle East, I compare nine historical cases which reduced national opium production by over 90 percent. The cases ranged from China (1906-17) to Vietnam (1990s). The majority of these nine national interventions—Imperial China, Iran, Laos, Turkey, Vietnam, Communist China, Pakistan and Thailand—had four things in common.

First, unsurprisingly, they all involved governments which perceived suppression as being in the national interest. International pressure was seldom enough to motivate states into action. Rather, governments chose to suppress opium due to concern for domestic opiate consumption and/or a belief that they could make economic or security gains from doing so.

Second, in all cases the state possessed authority in opium producing areas. While Imperial China, Iran, Laos, Turkey and Vietnam already enjoyed sufficient authority in opium growing areas, Communist China, Pakistan and Thailand identified state extension as the first step in a longer-term strategy. They put eradication on hold while they improved relations between opium farming communities and the state.

Third, all but two cases—China (1906-17) and Iran (1950 and 1960s)—offered farming communities an incentive to stop producing drugs. These incentives most often took the form of rural development and the promotion of social goods such as healthcare, education and clean drinking water.

Not only do incentives establish the perception that suppression is in the farmers' own interests but they can be a way of extending the state. One of the cases which failed to provide some form of incentive was China (1906-17), which enacted an intervention that was so repressive it contributed to the downfall of China's last imperial dynasty, as farmers sided with revolutionaries to overthrow the Imperial regime.

Finally, all nine case studies involved law enforcement and the forced eradication of opium crops.

The key lesson from the nine cases, however, was that forcefully eradicating opium or punishing farmers without providing them with alternative sources of income often further impoverishes communities and alienates them from the state. This may, in turn, cause or heighten conflict and lessen state authority. As such, not only can eradication inflate the very structural conditions which push farmers into the drugs trade in the first place, but it may force them to grow more opium to repay their debts to merchants and traffickers.So, while forced eradication will be necessary it should be sequenced after the state has secured authority over opium farming areas, and farmers have sufficient alternative incomes

Rapid and badly planned interventions in the drugs trade could increase the supply of heroin to the U.S. and other parts of the world. But a less aggressive policy, which instead offers farmers peace or improvements in their quality of life will strengthen the state, nudge some to growers stop producing opium and, eventually, make it easier for the state to eradicate the remaining crops.

As Trump acknowledges in his recent presidential order, the key to counter-narcotics is cooperation with source and transit states. Trump's key focus will be Mexico, as both a source and transit state. Demanding that Mexico take crops away from impoverished farmers is not going to stem the flow of drugs into the U.S. Worse case scenario, it could actually increase it. Instead, Trump should focus on long-term policies which will help strengthen Mexico, including funding for rural development, while avoiding any policies which might harm the Mexican economy.

This isn't being soft on drugs, it's being pragmatic. Ask John Kelly, Trump's Secretary of State for Homeland Security. He has argued that stemming illegal migration requires a holistic approach encompassing economic development, education and human rights. Let's hope that this long-term strategic thinking will be applied to counter-narcotics.

James Windle is a senior lecturer in criminology and criminal justice at the University of East London (UEL), and fellow of the UEL Terrorism and Extremism Research Center. He is the author of Suppressing Illicit Opium Production: Successful Intervention in Asia and the Middle East

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.