Conspiracy theories are nothing new. But, since the evolution of the internet, their ability to spread around the world has increased exponentially.

As of 2022, roughly 70 percent Americans see misinformation as a major threat to society, compared to 57 percent who see the spread of infectious diseases as a major threat and 54 percent who are concerned about global climate change, according to surveys from Pew Research Center.

But what can we do to stop the spread of misinformation?

"Once people have been radicalized or are deep down the conspiracy theory rabbit hole, it's actually very difficult to then counter argue and bring people back, because they've already personally invested a lot in a particular worldview," Sander van der Linden, a professor of Social Psychology in Society at the University of Cambridge, told Newsweek. "When you argue with them, they often just go further down the rabbit hole defending that worldview."

Rather than targeting misinformation itself, van der Linden, whose research looks at how people process (mis)information, how it spreads through online and social networks, and how to make people immune to false information, believes we should target its spread.

In the study of infectious diseases, scientists use mathematical models to understand the spread of an infective agent through a population.

"These models are used to try to understand who's susceptible, how people get infected, and how they ultimately recover in a population," van der Linden said. "It turns out that you can take these models that are used to study the spread of viruses and use them without much adaptation to study the spread of misinformation in social networks."

So, how would these models work?

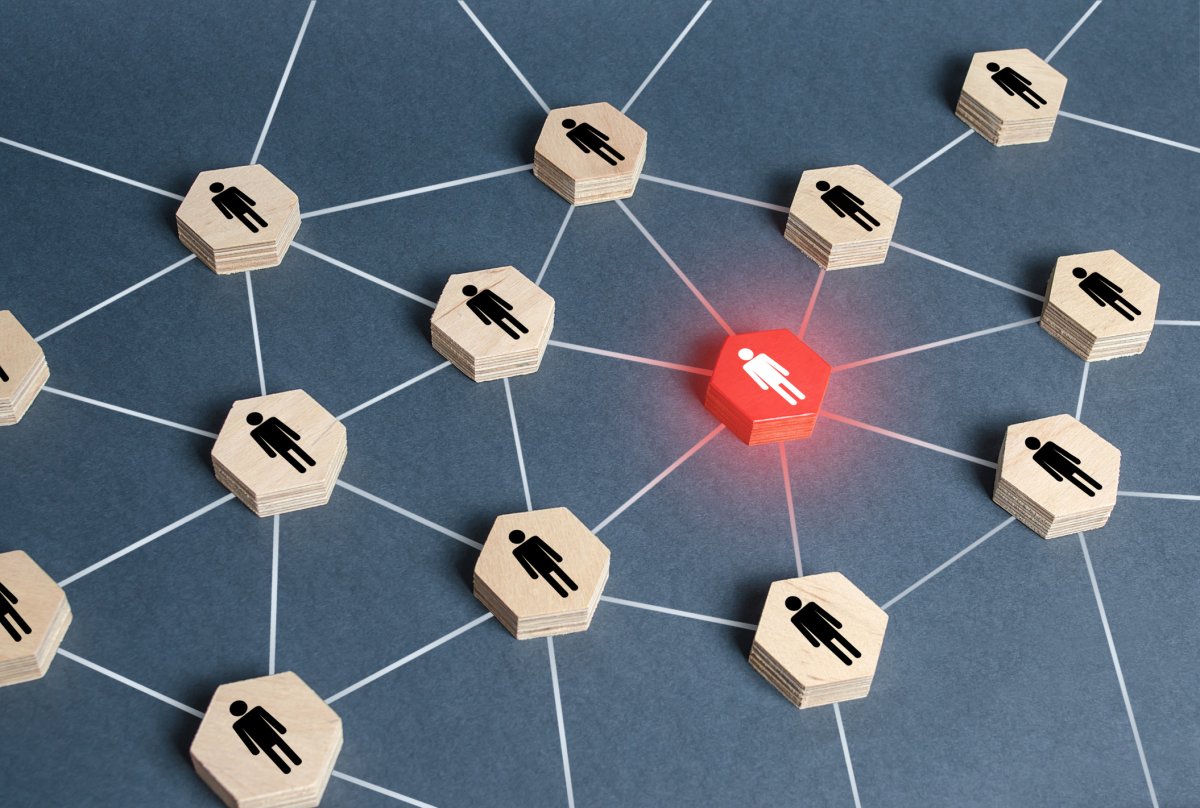

"If you think of a social network, you have patient zero—somebody who starts spreading misinformation," van der Linden said. "The other people in that network who come into contact with that individual become 'infected' after they've been exposed to the misinformation, and then there is some chance of those individuals transmitting the virus to other people in their network. And before you know it, everyone in a particular network has been exposed or infected.

"The 'virus' in this case is the bad information, not the people spreading it."

By modeling the spread of misinformation over time, we get learn how to intervene and inoculate people against it. This is what van der Linden describes as a "psychological vaccine."

"You pre-emptively expose people to a weakened dose of the misinformation 'virus' in order to build up their mental 'antibodies' that they need to gain some immunity to these manipulation techniques," he said. "It's not full immunity, but it helps people be more aware and identify and disarm these techniques when they happen in real life."

Of course, there are some differences between infection with a biological virus and fake news:

"With simple contagion models, they tend to assume that once you've been exposed to the virus you become infected," van der Linden told Newsweek. "But information doesn't always work that way. It isn't necessarily the case that, once you're exposed, you're immediately infected. But if everyone in your network is being exposed repeatedly, then there's a higher chance that you will become infected, especially if the misinformation aligns with your beliefs."

To test this theory, van der Linden and colleagues, working with Google, produced a series of 2-minute videos to illustrate six of the most common manipulation techniques used to spread misinformation. After extensively testing these in the lab, the videos were released into the wild in the 2-minute ad slot at the beginning of YouTube videos.

To test whether their campaign was a success, the team exposed one group to the "pre-bunking" ad and another control group to a short video about freezer burn. Eighteen hours later, the people who had seen the pre-bunk video were 5 to 10 percent better at recognizing manipulative techniques than those who had watched the video on freezer burn. The results of this study were published in the journal Science Advances in 2022.

"This approach doesn't seem to backfire in comparison to some other approaches that more directly challenges people," van der Linden said. "What's interesting is that conspiracy theorists actually seem pretty open to this idea of recognizing manipulation strategies. They don't want to be manipulated; that's kind of core to their identity. So they tend to be slightly more intrigued about our interventions on how to spot manipulation."

YouTube ads are one way to expose people to these "psychological vaccines," but not everyone uses this platform, and for some people these pre-bunking techniques will be introduced too late. To arm more people with these pre-bunking tools, van der Linden believes they should be introduced into the school curriculum.

"Every student should be taught a class on what a conspiracy theory is and how to identify them. What are the basic building blocks," he said. "I think we have to think carefully about how to integrate this into the curriculum over several years to make sure young people can develop lifelong immunity."

You can read more about how you can protect yourself from misinformation in van der Linden's book, Foolproof: Why We Fall for Misinformation and How to Build Immunity. Van der Linden will also be speaking about psychological vaccines and how not to be fooled at the New Scientist Live event on October 8, which can be attended online or in person at the ExCel Center in London.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Pandora Dewan is a Senior Science Reporter at Newsweek based in London, UK. Her focus is reporting on science, health ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.