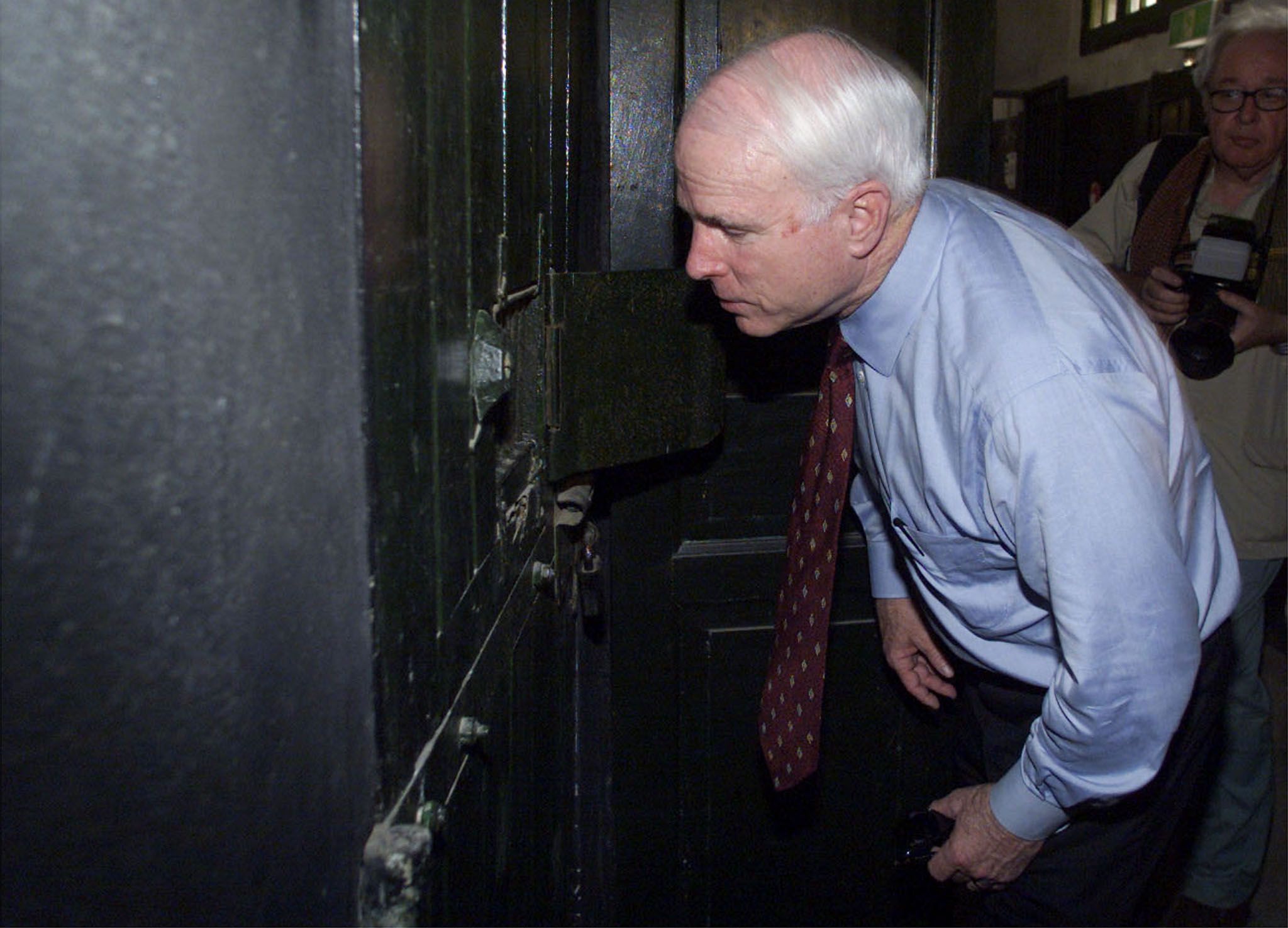

Newsweek published this story under the headline "VIET VETS FIGHT BACK" on November 12, 1979. In light of recent news about Senator John McCain's brain cancer diagnosis and its possible connection to Agent Orange exposure, Newsweek is republishing the story.

Shad Meshad, a graduate student in psychology, was 25 when he volunteered to go to Vietnam. As an Army captain, he put dead soldiers—piece by piece—into body bags, and still remembers every face, he says. "When I came home [to Birmingham, Ala., in 1970], I wasn't sure I believed in America anymore," he recalls. "I would cry and stay drunk to hide the pain." Once discussing the war with his family, he got so mad that he overturned a table and rammed his fist through a door. Gradually, however, Meshad made peace with himself. He joined the Veterans Administration in Los Angeles as a counselor and combed the area for troubled vets. His counseling efforts became so successful in getting vets to talk out their pent-up guilt and anger that Congress is now setting up 86 psychological centers based on his program. Like Meshad, the nation is finally getting some perspective on the Vietnam War and stepping up help to the 2.8 million vets who fought there. "The men who came home from World War II were heroes, but the Vietnam vets were different," says Dr. Jack Ewalt, a VA official. "The public felt either that they were suckers to have gone, or that they were the kids who lost the war." But a Louis Harris survey to be released this weekend on Veterans Day shows that a 2-to-1 margin, Americans now regard Vietnam vets as victims of a senseless war rather than perpetrators who share the blame. In 1971, about 50 percent held that view. "Just as an individual requires a period of calm and quiet after a traumatic experience, so does the nation," explains paralyzed vet Bobby Muller, head of the Vietnam Veterans of America, which has led the crusade for veterans' rights. "Now, maybe we're both ready to rationally come to terms with the experience."

CLOUT: The changing attitudes are producing more benefits for the vets. Last June, Congress approved a $25 million veterans' package that expanded drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs, set up a preventative health-care plan and established Operation Outreach—a network of counseling centers to be run from storefronts, not VA hospitals. Last year, Congress approved a tax credit for businesses that hire disadvantaged vets. And recently, 19 congressmen who served in the armed forces during the Vietnam War formed a caucus to help provide political clout. "There was no concerned lobby for Vietnam vets up here," says Rep. David Bonior of Michigan, who heads the group. "In previous administrations, it just wasn't smart politically to bring up the war again."

The Congressional caucus is pushing the Vietnam Veteran's Act, which would extend coverage under the GI Bill from ten years to twenty years for those who served in Southeast Asia. It would also permit veterans to use their educational benefits for private-sector training programs and provide compensation for problems related to Agent Orange, a chemical defoliant used in Vietnam that some say causes skin diseases and birth defects.

But the new legislation is running into opposition from an unlikely source: the Veterans Administration. VA administrator Max Cleland, who lost both legs and a forearm in Vietnam, says the proposed act is excessive and not sufficiently targeted for those who need assistance most. Cleland argues that GI benefits have substantially increased (more than $45 billion has already been spent on Vietnam-era veterans), and that the dangers of Agent Orange have yet to be documented. Instead, he favors Carter Administration proposals that would extend the GI Bill for two years for educationally and vocationally disadvantaged vets, and provide extra rehabilitation funds for those with disabilities. "We know that minorities and the wounded are suffering most," Cleland says. "This is what we have to focus on."

DOING WELL: Cleland cites statistics that show that Vietnam veterans are better educated than vets from other wars and that, on average, they are beter off than non-vets of the same age. Vietnam-era vets earn more ($12,680 in 1977, compared with $9,820 for non-vets aged 20 to 39) and have had lower unemployment rates (5.1 percent vs. 6.2 percent in 1978.) Even the jobless rate for minority-group veterans (6.3 percent) is lower than for non-vet minorities (7.5 per cent).

But critics like Muller say those statistics are deceptive, since they reflect all 9 million veterans who served between 1964 and 1973, not just the roughly one-third stationed in Southeast Asia. They cite a recent study by the Center for Policy Research showing that nearly half of those who actually served in the war still have serious physical and psychological ailments—from nervous disorders to drug addiction—and that more than 75 percent complain of marital and job problems and nightmares. Although the VA commissioned that survey, it argues that the study is incomplete.

ATROCITIES: The activist vets also say that the Vietnam War was especially traumatic emotionally. The country was deeply divided over the war, the great moral cause that justified killing in other wars was ambiguous at best in Vietnam, drugs were widely available, atrocities were televised regularly and, in the end, the U.S. lost the war. Far from getting a hero's welcome, the vets returned to a country that provided little emotional support for combat stress. "They were greeted by little brothers who asked if they had killed babies," says Charles Figley of Purdue University, an authority on combat stress. "The best medicine a country can give its veterans is love and understanding—and it didn't."

With few people to talk to and a variety of drugs to fall back on, Vietnam vets have occasionally snapped. Counselors recently found one living in a Goodwill Industries box in a California parking lot. Two months ago, a knife-wielding vet stormed the office of a California state senator, demanding better benefits. A fortnight ago, a vet held a West Virginia church congregation at gunpoint. Last year, police found a veteran shooting into the air in a Quincy, Mass., cemetery where several of his buddies were buried, crying, "I just want to die."

NO PARADES: But with the climate changing, Vietnam vets are starting to fight back—and to help fellow veterans readjust. The American Civil Liberties Union recently set up toll-free hotlines to help vets seek an upgrading of dishonorable discharges (and thus qualify for GI benefits), and 275 calls a day are coming in. Around the country, veterans' groups are becoming increasingly vocal about their needs; dozens of self-help groups now provide drug, alcohol and emotional counseling, job-placement services and just talk. "We don't need parades, plaques and certificates, just respect and recognition," says Randy Fowler of the Santa Rosa group Flower of the Dragon. "Like women and blacks, Vietnam vets are emerging and demanding dignity," says Yale psychiatrist Robert Lifton. "They are bouncing back—and not just licking their wounds, but declaring their worth."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.