In the fall of 2007, a young Democratic senator blocked President George W. Bush's nominee to the Federal Election Commission. "His record of poor management, divisiveness, and inappropriate partisanship makes him an unacceptable nominee," the senator said, adding that he was "particularly concerned with his efforts to undermine voting rights" while that nominee was at the Department of Justice.

The senator was Barack Obama. The nominee was Hans A. von Spakovsky, who'd devoted the previous two decades to rooting out suspected voter fraud, even when scant evidence of such electoral malefaction existed.

Von Spakovsky never forgot the slight. He spent the subsequent years — that is, the Obama years — continuing his calls into tighter voter identification laws, attempts that many say would disenfranchise poor and minority voters. He served as a fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, and on the Fairfax County Electoral Board in suburban Virginia, to which he wasn't asked to return for a second term in 2012. "He's a voter-suppression advocate, and he can't deny that with a straight face," a Democratic operative in Fairfax County told The Washington Post.

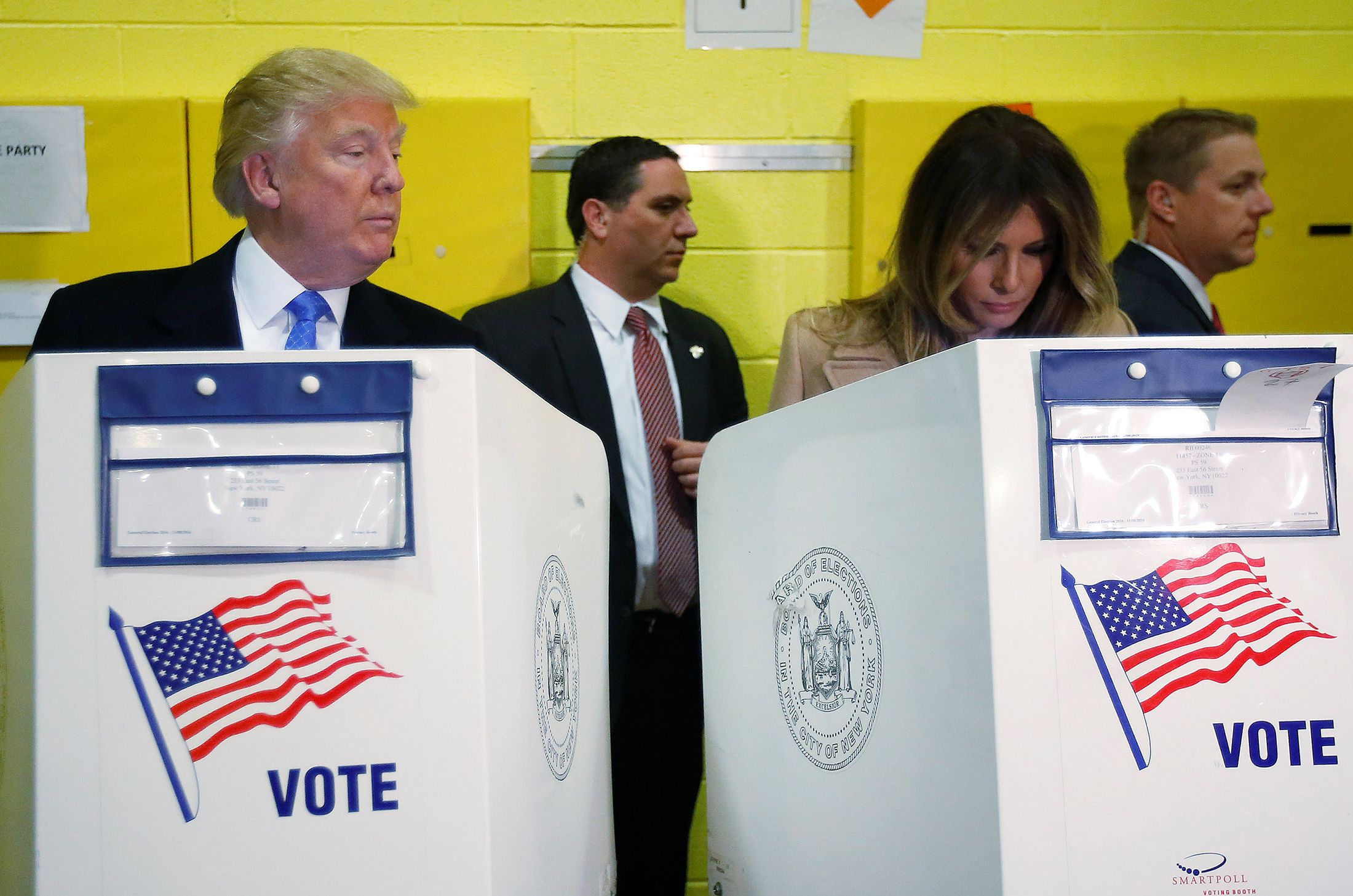

Late last week, von Spakovsky was named the newest member of the Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity. There is no evidence that the nation's electoral process, which is administered by states, lacks integrity. Rather, the commission stems from President Donald J. Trump's well-chronicled anger over losing the popular vote to Hillary Clinton by a margin of 2.9 million. Humiliation over that loss, coupled with an active imagination acutely attuned to right-wing conspiracies, have turned this obsession into a tax-funded federal imperative.

The agenda of the commission dovetails with what many say is Spakovsky's longstanding aim to pervert election laws in a way that favors Republicans. "The inclusion of Mr. Von Spakovsky does not inspire confidence," says Jonathan Brater, counsel for the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University's School of Law.

Richard L. Hasen, an expert on voting at the University of California at Irvine, told Newsweek that "the commission may vastly overstate the potential for voter fraud as a pretext for legislation making it harder to register and vote." In a blog post for Slate, Hasen predicted that the commission will try to unto 1993's National Voter Registration Act, the so-called motor voter law that made it much easier for people to register to vote, in part because it allowed them to do so while applying for or renewing a driver's license.

Von Spakovsky joins the commission as it comes under increasing public scrutiny. Though nominally chaired by Vice President Mike Pence, the voting commission is in fact being led by Kansas Secretary of State Kris W. Kobach, a longtime promulgator of voter fraud conspiracy theories. Kobach has requested information on voter registration from all 50 states; 44 have refused, with the secretary of state in Mississippi advising the commission's members to "go jump in the Gulf of Mexico." (The other six states haven't made their intentions clear.)

Von Spakovsky may be a troubling pick for liberals, but he's perfectly suited to a commission tasked with investigating imagined transgressions and reaching the dark, self-serving conclusion Trump plainly craves. The entire effort could be little more than an effort to "push a false narrative about widescale fraud," says Dale Ho, director of the Voting Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union. (Von Spakovsky did not answer Newsweek requests for an interview. Neither did Kobach.)

Ho says von Spakovsky's participation in the commission should be especially concerning because "he is a person who, through his entire career, has played fast and loose with the truth."

Born in 1959, von Spakovsky has Russian nobility on his father's side (his mother is German). He grew up in Huntsville, Alabama. "Although the civil-rights movement created tumult in Alabama during his childhood, he says that he has no memory of it," Jane Mayer wrote of von Spakovsky in a 2012 New Yorker profile that credited him with making voter suppression a core principle of today's Republican Party, alongside open-carry gun laws and defunding Planned Parenthood.

Von Spakovsky went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, graduating in 1981, then went to Vanderbilt University in Tennessee for law school. His entrée into Republicans politics, in the mid-1980s, came as the Reagan Revolution was at its pinnacle. As the head of the Fulton County Republican Party, which includes Atlanta and its suburbs, he helped institute stricter voter identification laws that seemed to undo parts of 1993's motor voter law.

During the legally contested 1999 presidential election, von Spakovsky told The New York Times that motor voter laws were responsible for the chaos in Florida because they "took away the ability of election officials to verify a voter's identify and makes it easier to file false registrations and vote multiple times," as the Times described his position.

No statistically significant instances of voter fraud were found in South Florida; Republicans' successful efforts to halt a full recount there handed the presidency to George W. Bush. Von Spakovsky then went to work for the Justice Department, where his work was nominally focused on voting rights—but in effect amounted to voter suppression. In 2006, it came out that von Spakovsky had used a pseudonym, Publius, to publish law-journal articles advocating for voter suppression laws. He also clashed with Justice Department officials who object to his plainly partisan inquests. "Mr. von Spakovsky was central to the administration's pursuit of strategies that had the effect of suppressing the minority vote," one former DOJ official told McClatchy Newspapers.

After the election of Obama in 2008, von Spakovsky joined the Heritage Foundation, where he continued to highlight what he called instances of voter fraud, both historical and contemporaneous. A paper he published in 2008 for the conservative Heritage Foundation, where he is now a scholar, warns that the nation has "an unfortunate and long history of ballot fraud." Yet he produces few examples, one of which is from 1844, another from a mayoral race in East Chicago, Indiana (population: 30,000), and another from a state contest in Tennessee where three poll workers did appear to tamper with election results. His most trenchant example was from the Illinois gubernatorial race — of 1982.

In 2014, he wrote for The Daily Signal, a Heritage-run news site, that Obama "denounces voter fraud as myth, while ignoring documented cases of blatant voter fraud." His trotted out a sole documented case, that of an Ohio woman, Melowese Richardson, who was sentenced to five years in prison after being convicted on four counts of illegal voting.

After the 2017 election, von Spakovsky eagerly parroted Trump's false claims of ballot-box stuffing. "There is no question that there are dishonorable people who willing to exploit the loopholes in our honor system," he wrote in a Fox News editorial co-authored with John Fund. The authors illustrated the seriousness of the problem with an example from 1996.

The paucity of von Spakovsky's "research" shows that voter fraud is no problem at all—but that it is an excellent wedge issue for the Republican base. His efforts have helped enact voter ID laws in 33 states. "Whenever a new law restricting the right to vote is introduced or accusations of voter fraud hurled, von Spakovsky invariably lurks in a corner," writes Ari Rabin-Havt of the liberal group Media Matters for Americas.

Now, he has the biggest platform of his career, as well as the attention of a plainly insecure president on a futile quest to prove that fraud in liberal states like California and New York cost him the popular vote. This time, there isn't an Obama to block him.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national affairs.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.