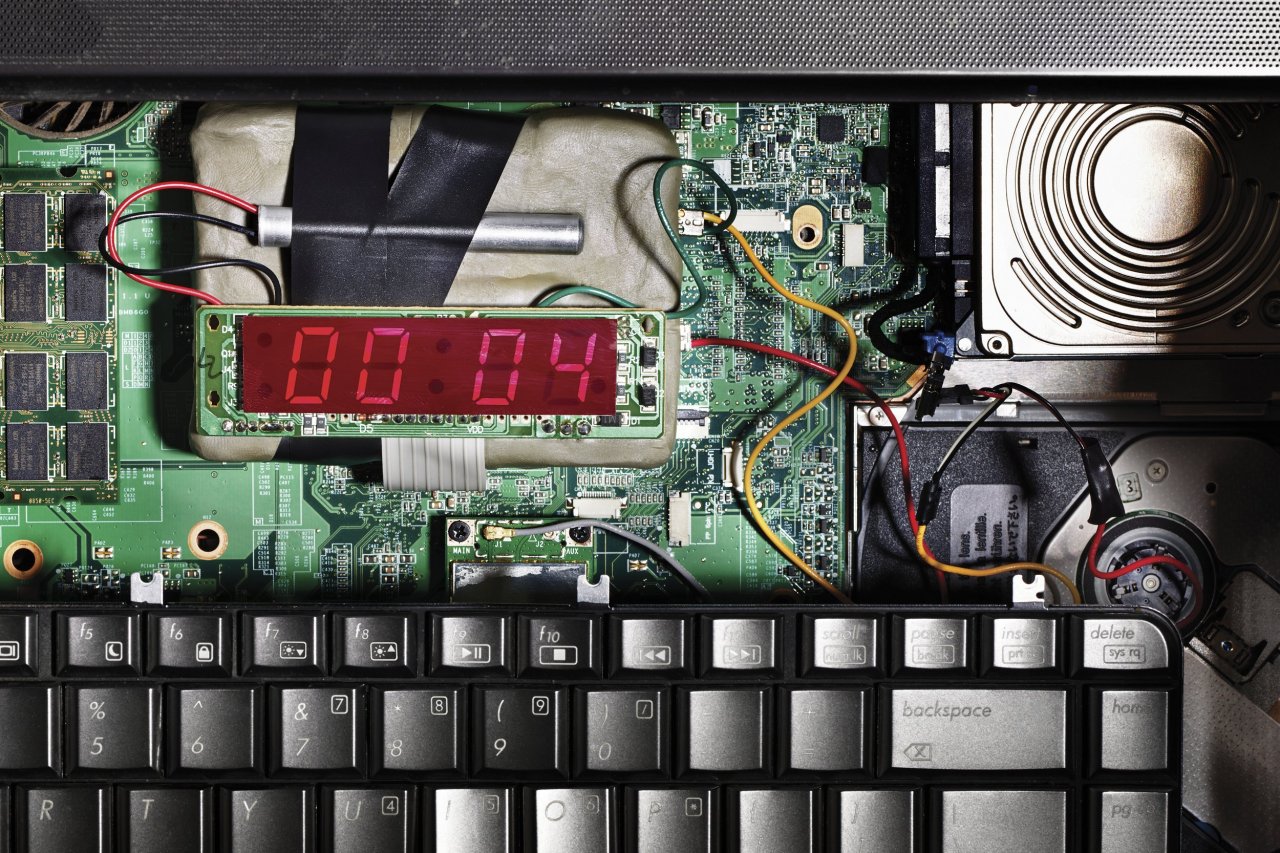

One week before the recent massive hack attack shut off access to Twitter, PayPal, Airbnb and dozens of other major websites, I was at an off-the-record conference with leaders of some of the country's biggest companies, discussing cyberthreats. Like soldiers in one of the landing crafts approaching the beach on D-Day, the CEOs seemed resigned to their grim fate. A destructive attack was inevitably going to rip through some, if not all, of them. They felt sorry for themselves and one another.

And most weren't even imagining how bad it's going to get. IBM CEO Ginni Rometty has said cybercrime is today's greatest threat to global business, apparently putting it ahead of nuclear war, climate change or an alien invasion.

We're in an age of world-changing technological wonders—self-driving cars, artificial intelligence, digital currencies, virtual reality, speech recognition that's more accurate than humans. We're putting chips and software into everything and connecting it all to a global network, creating a giant hive of people, places and things. These advances can make life easier, safer and more prosperous for most people. But technology doesn't have morals, and bad people with evil intentions can hijack any invention. Your cool new electronic-connected toilet? Just wait until a hacker turns it against you.

As the world grows ever more digital, hacking is at the same time becoming ever more profitable, ever more destructive. Yet no one knows how to stop the increasingly sophisticated hacking. No research lab is on the brink of a breakthrough. No security company makes software that's impenetrable. Meanwhile, cybercrime is turning into a booming industry. Enterprising assholes have even created hacking-as-a-service. Pretty much anyone with a credit card and a surfeit of bile can head online and configure hacking tools to go after any entity. "You really have to have an hour-by-hour sense of paranoia now," Mike Campbell, CEO of financial software company International Decision Systems, told me earlier this year.

The October 21 attack against DynDNS gave us all a taste of a doomsday scenario. A hacker deployed tiny pieces of software called Mirai bots to find millions of vulnerable devices connected to the internet, including web cameras, baby monitors and DVRs. The software then hijacked the devices and told them to incessantly ping the Dyn servers, which act as a kind of switchboard for many popular websites. By overwhelming the switchboard, the hack essentially shut down access to the sites Dyn served.

Starting at 7:10 a.m., most of the East Coast could not use PayPal, Amazon.com, Reddit, GitHub, The New York Times, Twitter, Netflix, Spotify and a long list of other sites that have become enmeshed in our lives. Two more waves of the same attack rendered most of the sites useless until late afternoon.

It was a weird feeling to be on the other end of that day's attacks. I realized something was wrong early that morning when I tried to go on PayPal to send money owed to a friend and got a blank screen. I then tried to open Twitter and got the same blank. I typed in a couple of other sites, and they worked. I clicked on Spotify to play some background music, and it froze, cut off from its servers in the cloud. I'd stopped buying downloadable music years ago, so if I couldn't stream, how was I going to listen to the Fitz and the Tantrums song stuck in my head? I suddenly realized how much I relied on these web services. It wasn't a big leap to sense the panic I'd feel if, say, the Russians disagreed with our election outcome and launched a gargantuan attack that knocked out all of the web for days. Like millions of others, I'd be frozen out of work and play. I think I'd curl up in a ball and watch my cat sleep.

Companies afflicted by the Dyn attack must have lost millions of dollars in business. I've not been able to find any official tally yet, but cyberattacks cost companies $400 billion a year, insurer Lloyd's of London estimates—and that doesn't even start to measure the damage from losing customers' confidence and the rocketing costs to companies now in the arms race to protect their systems from hackers.

Attacks like the one on Dyn are by no means the only kind of cybervillain activity. Hackers broke into Yahoo and stole names, passwords, birth dates and other personal info from 200 million users, allegedly to be sold to identity thieves. Target, Home Depot and P.F. Chang's all had their systems raided to steal credit card numbers. North Korean hackers, lacking any sense of irony, broke into Sony and released executives' emails to try to extort the company out of releasing The Interview because the movie portrays that country's dictator, Kim Jong Un, as goofy and incompetent.

North Korea, Russia and China seem to be at the forefront of state-sponsored hacking. The Russians broke into the computers of the Hillary Clinton campaign in hopes of influencing the election. Eccentric security pioneer John McAfee believes the uptick in DNS attacks is a way for a foreign hacking corps to probe the U.S. internet for weaknesses, hoping to learn how to take down the whole thing at once. "They will analyze this attack and come back later with a more serious attack," he told Newsweek in October. "Anticipate that these will be exploited in a big way."

The most menacing new hacker trend may be the rise of ransomware. A hacker inserts code into a company's system that then holds the company's data hostage. The company is told to pay a ransom or the data will be destroyed. The FBI has said more than $1 billion was paid to ransomware hackers last year.

Kidnapping data will soon come to seem like petty antics. The more we connect critical devices, machinery and robots to the internet, the more dangerous ransomware starts to look.

At my table at the conference I mentioned at the top of this article were executives from one of the big car-rental companies. Someone raised the point that within a half-dozen years, most of the cars in its fleet will be connected—in which case, they'll be vulnerable to hacks that could, as has already been proved, take control of a car. What if a sophisticated hacker group took command of all of one company's rental cars—many of them at that moment on a highway somewhere—and demanded $1 billion or it would crash them all? The executives looked on numbly. They hadn't thought of that.

In the past year, Johnson & Johnson warned that its insulin pumps could be hacked, and a cybersecurity company found that a St. Jude Medical pacemaker could be vulnerable. If a bad actor found a way to plant software time bombs in vast numbers of these at once, it could demand ransom by threatening to kill people.

On top of all this, here comes artificial intelligence—software that can learn. One of the creepiest scenarios that concern security experts is the idea that AI-based hacking could learn to be you. Let's say an AI bot could get into your email, calendar, search history, Facebook page and music service. It could learn enough about you to mimic you—maybe autonomously concoct an email or chat conversation with your boss or your mother. We already know about identity theft. This possibility is far more personal and terrifying. It is stealing the self. It's one thing to steal our credit card numbers. It's a much deeper psychic blow when an intruder can threaten to destroy our relationships.

A persona-stealing hacker might demand ransom to not ruin your marriage. Or such a hacker might be looking to impersonate someone important to go after a bigger prize. A truism of cybersecurity is that the weakest link is always people. Security software can put locks and barriers around computer systems—enough to make it challenging and costly for hackers to break in. Hackers hate that. But if just one person can be fooled into giving up a password or authentication code, a hacker can walk into a system through a wide-open door. If an AI bot can mimic a person, chances are, it can use that to fool someone into giving up the keys to a system. ("Hey, Mary. Had a great time with you at the Ronda Rousey fight last night, but the five martinis afterward wiped out too many brain cells, and I forgot the missile-launching code. Can you help?" said the bot.)

All these new hacks make the age-old cybersecurity worries about someone shutting down the electric grid or opening a dam seem quaint.

While the amped-up sophistication of hackers poses a threat to our way of life, it also doesn't mean we're inevitably doomed—just as the invention of the nuclear bomb hasn't brought civilization to an end. Companies and governments spend around $150 billion a year on security software and tactics, doing everything they can to stay ahead of hackers or find the bad guys and prosecute them after a breach. Scientists at big companies like IBM and Microsoft and small companies like Darktrace and Jask are constantly working on new ways to defeat intruders. The coolest new security technology relies on AI to learn about normal activity in a system so it can instantly recognize anything strange and shut it down. Companies are protecting themselves by, for instance, never storing all their data in one place. Any large company or government agency will tell you its systems get hit by hackers thousands or even millions of times every single day, and almost all of them get stopped, or the damage stays limited, thanks to cyberdefenses.

Yet that's not enough. Any break-in can do enormous damage, and the most dangerous hackers always seem to be a step ahead of the defenses. No definitive solution is in sight. The October Dyn attack showed that hackers will always find the most vulnerable point and exploit it. Companies spent billions locking down their giant data centers, but hackers slipped splinters of software into networked DVRs and baby monitors and plunged a large chunk of the internet into darkness. The more things we connect, the more vulnerabilities we create.

To state the obvious: The worst hasn't happened yet.

And seriously, don't buy a connected toilet.