Snow is turning red across Alaska and much of Canada's Rocky Mountains, threatening the future of the frozen glaciers.

This "watermelon snow," also known as "glacier blood," is caused by the blooming of a type of pink-colored algae called Chlamydomonas nivalis, which flourishes in freezing temperatures.

This pink coloring makes glaciers much more prone to melting as the colored algae cause sunlight to be absorbed rather than reflected, heating the surrounding ice.

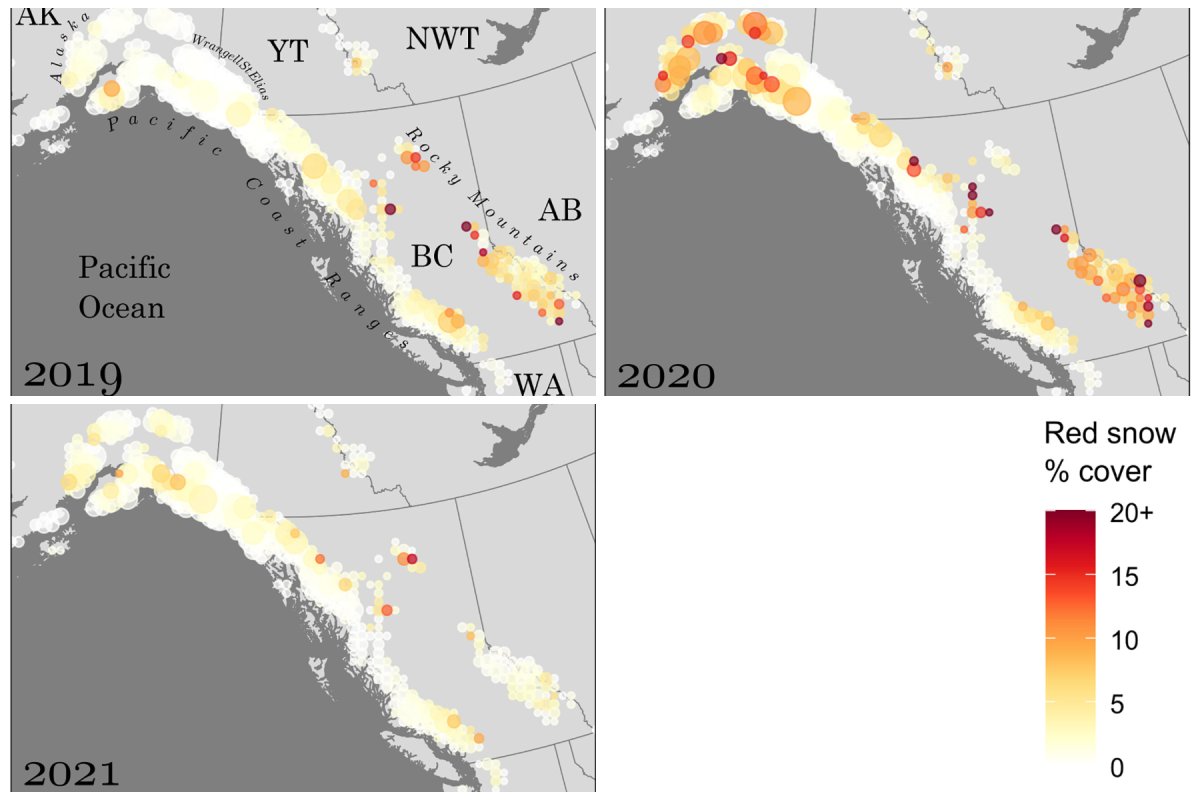

A recent study in the journal Science Advances found that this watermelon snow has now crept across 5 percent of the total glacier area in northwestern North America, including mountains in Alberta, British Columbia, Alaska, Idaho, Montana and Washington State.

Some individual glaciers saw up to 65 percent of their area covered in the pink algae during a single season, which the study estimates caused as much melting as a 3-centimeter (1.2-inch) average meltwater equivalent across the surface of the glacier.

"The melting is due to dark colors absorbing more heat than light colors," Lynne Quarmby, paper co-author and professor of molecular biology and biochemistry at Simon Fraser University, told Newsweek.

"The algae we study grow on the snow overlying rocks, frozen lakes and glaciers. They accelerate the rate of snow melt and when the glaciers are exposed, they begin to melt faster because liquid water is darker than the white of snow and ice, which is very good at reflecting the incoming energy back out into space," she said. "So how do the algae make the snow melt faster? It has to do with them being red and absorbing more energy (i.e. reflecting less back out into space than white snow). Because the cells need liquid water to grow, this melting stimulates more growth, more darkening and more absorption of incoming energy."

The researchers made these discoveries using thousands of satellite images taken between 2019 and 2022 and determined that the watermelon snow was having a significant impact on the rate of melting of glaciers. The algae was present on 4,552 of the 8,700 glaciers studied.

However, the impact that the algae is having on the glaciers and snowpack is mild in comparison to the effects of climate change and global warming. In fact, the glaciers are melting so much due to climate change that these algae are disappearing altogether.

"There is significant year-to-year variation in the extent and intensity of the blooms. We don't yet have enough high-resolution data to address whether there is an overall expansion of the Watermelon Snow," Quarmby said.

"While the presence of a bloom can have a significant impact on the rate of melting, the overall global effect of snow algae is small relative to the impact of increasing temperatures due to greenhouse gases added to the atmosphere by humans. Given that warmer temperatures stimulate algal growth, it is fair to say that the algae are exacerbating the melting caused by climate change. They are a small but amplifying feedback loop."

In 2020, the glaciers along the coast of the Pacific Northwest began to melt early in the spring due to abnormally high temperatures, meaning that in some locations, the algal blooms never developed at all.

"What is very clear from our data is that in 2020 when there was an early summer extreme heat dome in southwestern British Columbia, the blooms failed to form. In other words, evidence indicates that climate change will have a serious impact on this microscopic ecosystem," said Quarmby. "Awe-inspired when viewed covering a glacier, spectacularly beautiful under a microscope, and holding untold secrets about life in an extreme and ephemeral environment, this ecosystem appears headed for extinction."

These algae, despite acting as heat sinks on the glaciers, also absorb CO2 from the atmosphere during photosynthesis.

Watermelon snow is seen around the world, and therefore, so are its effects on shrinking glaciers.

"This is a global phenomenon," Quarmby said. "Watermelon snow was observed in the Arctic by early explorers (John Ross' painting, the Crimson Cliffs, is of watermelon snow on the coast of Greenland). Watermelon snow still blooms in the Arctic today. It is found in the Alps, New Zealand, Antarctica, even Mount Olympus! The basic requirements seem to be snow fields with a prolonged melt season. If the snow melts out too fast, the blooms don't have a chance to form. If there is insufficient warming to provide liquid water, blooms won't form."

As glaciers shrink further, the melting effect of the remaining watermelon snow algae may be even more damaging to the ice and snow.

"As the snowpack dwindles, these blooms are going to become increasingly concentrated and smaller and smaller," Scott Hotaling, a Utah State University ecologist, told Candian news CBC.

"The melting characteristics of that snow algae are going to become increasingly important. When there's only a small amount of snow left, anything that affects that matters more."

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about watermelon snow? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Update 01/10/24, 11:29 a.m. ET: This article was updated with comment from Lynne Quarmby.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.