On a rainy night in New York City last December, a man in a leather jacket stood alone in a dark parking garage just across from Penn Station. He held a briefcase tightly and wore a straw fedora that hid his eyes. Inside his case were samples of his specially milled cricket powder, created using a process developed with funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture that, if all goes right, could change the food industry.

A Florida native, Dr. Aaron T. Dossey is one of the main suppliers fueling a burgeoning insect boom. That powder, his latest product, was made for Exo, an insect protein bar company. His company, All Things Bugs, has also supplied cricket protein bar company Chapul, as well as Six Foods's cricket chips.

Since the United Nations came out with a report in 2013 recommending insects as food, entrepreneurs, restaurants and farms have been scrambling to cash in. The report hails the environmental benefits—since insects are cold-blooded, they burn fewer calories and therefore need less food than chickens or cows. Plus, they can eat waste products that are difficult or impossible for mammals to stomach. Since agriculture is responsible for about a quarter of the greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, and the crops needed to feed livestock make up a large portion of global agricultures, little bugs have the potential to lead to huge improvements in climate change.

Insects are also highly nutritious and an excellent source of protein. According to Jarrod Goldin, one of the founders of Next Millennium Farms, studies have shown they have an almost perfect ratio of omega-3 to omega-6. That could be huge for public health: An out-of-balance omega-3/6 ratio in the Western diet is thought to be a contributor to health problems ranging from cardiovascular disease to cancer. Insects are also high in iron, which is the leading vitamin deficiency worldwide, according to the World Food Programme.

And if that's not enough to convince you, Goldin predicts there might be even more excitement over possible prebiotics in insects' exoskeletons. Prebiotics are a type of carbohydrate that helps support gut health by acting as food for the "good bacteria" that live in your gut. Goldin says his company is running prebiotic tests on his cricket powder right now.

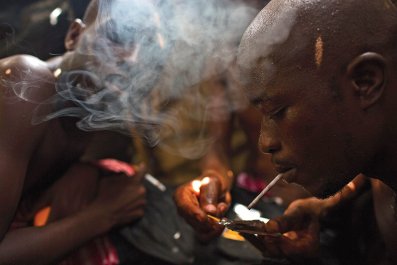

Insects are already a part of the average healthy diet for much of the rest of the world. In Australia, witchetty grubs are dug out of the ground and eaten for their high fat, high protein and almond taste. When the Spanish first encountered merchants selling the eggs of the aquatic axayacatl bug in Aztec markets, they called it "Mexican caviar." But in Western culture it's still a novelty (or accident) to ingest insects. And even though people worldwide have been eating bugs for a long time, raising them by the thousands and milling them into a powder is uncharted territory.

Because the Western world has been slow to take to insects, we don't yet have a full understanding of the allergies and toxins that could be associated with them, nor do we have research on the proper safety practices we would need for a viable edible-insect industry. As a result, U.S. regulatory agencies haven't taken a strong stance on the safety of bugs, and that, in turn, has stifled industry growth, according to the U.N. But that could change soon: Researchers are now working with businesses to fill in the knowledge gaps and keep insects safe as the industry explodes.

The GRAS Is Much Greener

Dossey calls himself a "recovering academic." As a postdoc biochemistry and microbiology researcher, he found his prospects for faculty positions limited. Then one day he got into a discussion over lunch about edible insects with some of his entomology friends and Daniella Martin, host of the insect cooking show Girl Meets Bug. Dossey figured he could compete in the market for insect foods because of his chemical and molecular biology knowledge. Armed with a Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation grant and a $20 blender, he started his business in a small Florida apartment.

At first he experimented with recipes for protein bars. Then he recognized he'd be competing with the acumen of the elite university business graduates behind Exo and Six Foods, so he shifted strategies: "I thought, Maybe I can just be the ingredient guy."

As Dossey developed his cricket powder, he reached out to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to figure out safety guidelines. He says its answers were vague, and some steps in the process the agency laid out were missing. So he applied for grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to initiate his own research into expected shelf life, potential allergens and how much heavy metals will stay in the insects' bodies from their feed.

The good news is that the USDA appears willing to fund this type of research. The director of the department's National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Dr. Sonny Ramaswamy, is a card-carrying entomologist who has been excited by insects' potential for a long time. The unabashed insectophile, who prides himself on his delicious curried cricket dish, is now the presidentially appointed head of an agency that provides funding for research.

Many researchers believe insects could be safer for human consumption than livestock. "Bird flu, swine flu—this transmission of a virus from an animal to humans will not happen when it comes to insects," says Jørgen Eilenberg, a professor at the University of Copenhagen who specializes in insect pathology and helped review the U.N. report. "Many insect viruses are so specialized they only affect one host." He says it's essentially the same with the bacteria and fungi that can infect insects: They do not affect humans.

But there are still some safety concerns. People allergic to shellfish might also suffer when eating insects, because the two are so biologically similar. It's also still unclear what allergens could carry over to insects from their feed. For example, if a grasshopper eats feed containing gluten, will it still be gluten-free?

To start identifying what allergies might be associated with insects, Dossey has teamed up with the University of Nebraska (fun fact: the U of N's sports teams' nickname used to be the Bugeaters) to find out. Dossey says genetic sequencing would be the next step, but that would require more funding. To definitively prove allergic reactions, researchers would need to do even larger and more expensive testing on animals and humans.

Information about allergens and toxins is key to working with larger manufacturers and shipping companies. That's why you might see something like "Manufactured on equipment that processes products containing peanuts" on your Girl Scout cookies box. And because the average U.S. consumer considers insects disgusting, manufacturers are wary about having to disclose the fact that traces of bugs could show up in other foods.

The edible insect industry is still in its infancy, but it's growing fast. Exo raised $1.2 million at the end of last year on Kickstarter. Next Millenium Farms just bought a bigger facility, where it is producing around 10,000 pounds of crickets a month. All Things Bugs milled around 30,000 pounds of crickets in 2014 and received preliminary news that Dossey could be getting another grant from the USDA to increase efficiency.

Yet the industry needs to wrestle with regulatory tangles before it can really take off. Getting confirmation from the FDA of the Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) designation would be a huge step forward. A company doesn't have to submit food products for GRAS in order to sell them, but Dossey says some of the largest manufacturing and shipping companies only work with foods that have it. "GRAS is the holy grail," he notes.

Ramaswamy says the proteins you get from an insect are basically the same as the ones you might get from a chicken or pig. According to the U.N. report, 2 billion people around the world eat insects on a regular basis. Yet no company has tried to prove to the FDA that insects are a safe food for humans. "The agency has not been notified of any determinations of GRAS status regarding use of insects as food," an FDA representative told Newsweek.

One reason might be that GRAS confirmation is an expensive undertaking for small startups; Dossey says one consultant quoted him $250,000 to get his powder researched.

The lack of FDA oversight on the issue filters down to local regulators who enforce their guidelines, and the vagueness has created confusion for restaurants interested in serving insect proteins. Gillian Todd, former manager of New York-based Antojeria la Popular, says her Mexican restaurant got a lot of attention in 2013 for serving bug dishes like the "Grass-Whopper." She says the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene pressured the restaurant to stop serving insects because its supply wasn't from an FDA-approved source.

"Our inspector found they had dried crickets in a bag they claimed was from a California supplier," the department told Newsweek. "But it was unmarked. Bags must be marked with the supplier and the contents, and it must come from an approved source."

Todd says her restaurant couldn't find such a source. Antojeria ended up closing shortly afterward. Meanwhile, other New York restaurants serving grasshoppers as a traditional Mexican ingredient became worried that their unapproved supply chains could also get them shut down.

Some companies have benefited from developing good relationships with local regulators. Laura D'Asaro is one of the owners of Six Foods, which makes cricket chips. She says the company was able to get approval of its products from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. This in turn helped it get on grocery store shelves throughout the state. "Most of the health departments didn't know what to think about it," she says. "They, like everyone else, had thought of them as pests to try and keep out of food."

The FDA does have some clear regulations for insects as human food. For example, producers have to follow the same best practices that apply to other foods, like proper labeling and keeping the products contaminant-free. They can't be "wild-crafted"—meaning you can't go pick grasshoppers out of a field and sell them at a farmers' market. And the insects have to be raised explicitly for human food. But everyone in the industry agrees more work needs to be done.

The biggest hurdle for edible insects in the U.S. and Europe will be the yuck factor. Many believe that the best way to get Westerners to overcome their aversion is to start introducing insects into children's diets early on. "I have two daughters, and their favorite food is plain white pasta with butter," says Goldin. He's excited that some companies are now making a pasta with the health and environmental benefits of cricket powder that could satisfy his children's finicky appetites.

Kids, being highly adaptable creatures, might take to bugs more quickly than adults. Ramaswamy says that when he was a practicing entomologist he loved to work with children because you can use insects to introduce them to abstract concepts like ecology and climate change. "I would go to schools and take insects with me. I'd pop a live caterpillar in my mouth and start chewing on it and eating it. They would go crazy. Of course, the boys would run over and say, 'Oh, I want to do that.'"