Werner Herzog has made so many movies he's lost count.

"I've never counted them myself," he recently told Rolling Stone. "I don't care."

In fact, there is a lot Werner Herzog does not care about: Hollywood orthodoxy, the daily minutia of social media, watching other people's movies (he watches "three or four films per year, not more," he tells me), limiting himself to safe or predictable filming locations (an active volcano? A reserve full of grizzly bears? Sure), the rigidity of pure fact (his documentaries sometimes contain fictionalized elements). Herzog does not care about me either, I don't think, but he spends 15 minutes on the phone answering my questions anyway. He has a movie to promote: Salt and Fire. It's his 71st or 72nd or 73rd movie—who cares—and it's an unusual thriller about a hostage-taking situation set against an ecological disaster in Bolivia. Veronica Ferres plays the ecologist who has arrived in South America to investigate said disaster, Michael Shannon the sinister corporate goon who holds her hostage, while the salt flats of Bolivia (with a supervolcano lurking nearby) provide an unnervingly otherworldly setting.

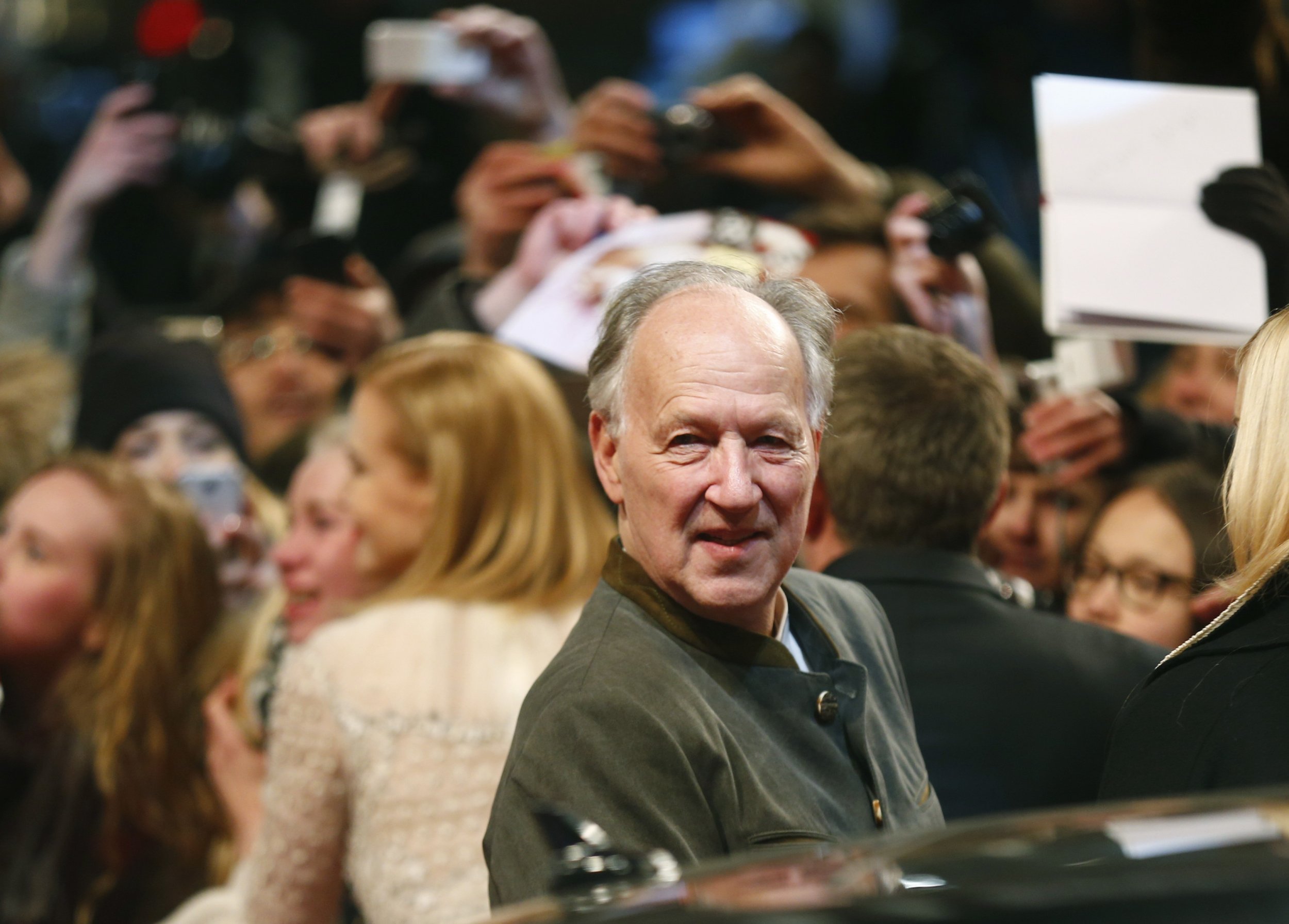

During those 15 minutes on the phone, Werner Herzog the man lives up to the Werner Herzog the legend: the deep Germanic accent, the terse morsels of uncompromising wisdom, the intense creative restlessness. Salt and Fire is his second film in as many years with an ecological backdrop; Into the Inferno, Herzog's 2016 Netflix documentary, found the director trailing a volcanologist around the frightening and beautiful world of active volcanoes. And he's not afraid to tackle the less tangible evils that plague us; Herzog's much-discussed recent documentary about the internet, Lo and Behold, narrows in on the extremes of the virtual world.

The remarkably prolific gonzo filmmaker has been making films since 1968, which means there's 49 years worth of writers and contemporaries trying (and frequently failing) to describe him. Words like "provocative" and "hallucinatory" tend to pop up a lot. Janet Maslin, the New York Times critic, called him "the consummate poet of doom." François Truffaut called him "the most important film director alive." Klaus Kinski called him "a miserable, hateful, malevolent, avaricious, money-hungry, nasty, sadistic, treacherous, cowardly creep."

I will let Herzog speak for himself.

I couldn't help but notice you've been pretty focused on natural and ecological disasters in your work lately. Between Salt and Fire and Into the Inferno, what precipitated this interest?

Well [clears throat loudly], I'm not really an ecological activist. That would be too farfetched. The disaster described in the film doesn't exist in reality. It could exist, but it doesn't. You still can feel a background from the short story by Tom Bissell, Aral, which is [set] on Lake Aral in central Asia—a gigantic lake which has dried out. Now fishing boats are sitting on sand and rusting away.

You filmed in the salt flats of Bolivia. What was it like?

Logistics is not that easy, but that's OK. It was fairly high up, so some of my crew and actors had problems with the altitude and had to acclimatize, but we had a very very short time of shooting. Only 16 days shooting somehow shrunk to a minimum of days, which was kind of difficult to handle. But it's OK. You have to deal with it.

I gather that you like shooting in extreme locations. Does anything make you nervous?

I'm not really looking out for difficulties. I was looking out for a location that looked like not from our planet. It really looks extraterrestrial. [Like] from science fiction.

Is there anywhere on earth that you would like to shoot but have not been able to?

There are lots of places that would be fascinating. But I could do a film in a motel room outside Los Angeles. It's not that much how exotic an environment looks. It's always the substance of the story I am after.

Of course. How did you conceive of this story? How did this particular hostage plot come to you?

I was fascinated by Tom Bissell's short story, Aral. I'd been talking with him about it for quite some time. I had a feeling I should do it since I found a very, very fine actress, Veronica Ferres, who's arguably the only real big star in Germany and somehow not properly used yet in films. She hasn't really been discovered yet. And of course Michael Shannon as the partner, who takes her hostage. I knew they would create great chemistry. Casting is always chemistry.

There are many great hostage films throughout the history of cinema. Do you have a favorite?

[long pause] You mean...

A movie, like, about a hostage crisis of some sort?

I've never seen a movie about that. I don't see that many. I've seen three or four films per year, not more.

Wow. That's not very many. I guess you're busy working.

Yeah, yeah. I'm not that fascinated watching movies.

You just like making movies.

Yes. And I do read.

Did you see the film that won Best Picture at the Oscars? Did you see Moonlight?

No. I haven't seen a single one of the Oscar-nominated films.

Are you reading anything great right now that is worth mentioning?

Yeah, let's not go into that [laughs].

OK. So two of your recent films, Salt and Fire and Into the Inferno, both involve volcanoes. What fascinates you about volcanoes?

There is something very cinematic about volcanoes. You can see clearly into the inferno. Since I decided not to shoot in central Asia on the real Lake Aral, [we were] in the salt flats of Bolivia and there was a volcano right at the border, at the shores of the salt flats. I decided to incorporate it into the movie.

Much of your work has revolved around these environmental themes recently. Has Donald Trump's presidency made you more concerned about the possibility of some sort of environmental catastrophe?

Well, I think the environment is more something that's ruled by the individual states. I want to point out that California is moving ahead with solar energy and wind power and whatever. You don't care so much about what any American president thinks about the environment. Besides, we are waiting too much for presidents or international bodies or consortiums to do something. Every one of us could easily reduce waste or energy by a quarter. Every single one of us could do that. I'm not waiting for politics to do something good or to do something stupid. I have reduced my, quote unquote, "waste of energy" by at least 25 percent.

But President Trump himself is a climate change skeptic. Is that concerning to you?

Sure. But whether he's a skeptic or not, he will not decide much of the battle.

You were quoted recently in an interview saying that you regard Trump with "great, strange fascination." Some people interpreted that to mean that you have some admiration for him. Is that accurate or is that a misreading?

Who misread it? [chuckles] I have never seen that anybody misreads it. Of course, everybody knows there's something—something unique and something we haven't had before. The first independent in the White House.

But you don't admire him or you do?

No, come on. Forget about it. I have never admired a president.

And certainly not this one.

Don't, don't drag me into politics. That's not what our interview—we are talking about Salt and Fire. And of course Trump is the president of the United States because he was voted into office, period. We have to deal with him now. Or the world has to deal with him.

Are there any cinematic opportunities that have been opened by this new reality?

No.

I'd love to talk about your documentary Lo and Behold as well. I've never seen the internet approached in quite the same way. Did making the film change any of your own digital habits? I know you've been skeptical—

I don't have any digital habits. Skeptical about it? [laughs] No, I don't have real digital habits. Yes, I do use the internet for email and sometimes I do read the newspaper online.

Did it change how you view the online world?

No. But I'm a good observer, I think. Strange enough, although I still do not use a cell phone, I think I made the only real competent film on the internet.

The only one?

I guess so. Because whatever you see out there is purely technical.

Your film was very concerned with the extremes of internet life: the people who are addicted to the internet, for instance, and then on the other extreme, the people who were allergic to WiFi signals. What you're saying is there is no other film that captures it quite the same way?

Yeah, and of course there are certain glories of the internet that you haven't seen as explicitly. For example, video gamers joining into research of very complex foldings of enzymes, which the biggest supercomputers in the world could not solve. It's something totally unprecedented and glorious.

Related: What Werner Herzog's new film 'Lo and Behold' reveals about the internet

Do you have any desire to live among those people in West Virginia, completely cut off from the digital world?

No. I wouldn't. And besides, they are so-called—I say it in quotes—refugees from electronic smog. Because in West Virginia all radio waves are shut off because of a gigantic observatory. Some sort of a—how do you call it—a huge disc that connects radio waves from outer space.

Let's talk about Queen of the Desert. How did you find working with Nicole Kidman?

Oh, she's one of the finest actresses we have anywhere in the world. It's a little bit bizarre that the film is going to be released theatrically only a week after Salt and Fire. Queen of the Desert should have been released a year and a half ago. But things happen as they happen.

I couldn't help but notice the film received a pretty negative critical reception, which is unusual for you.

No, some of my best films have had the most negative reactions by reviewers. That was two years ago at the Berlin Film Festival because the reviewers expected a film that they didn't see. [They have] all these prefabricated ideas. Maybe the advantage that the film comes out one and a half years later [is that] all of a sudden these wrong expectations have subsided and you can see the real movie.

Are you working on any new films right now that you'd like to mention?

Yeah, yeah. I do have three, four feature films I am preparing.

Before I could ask about these several films-in-progress, the publicist cut us off: We were out of time.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Zach Schonfeld is a senior writer for Newsweek, where he covers culture for the print magazine. Previously, he was an ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.