Parading up and down Goma's main street, Col. Vianney Kazarama and his men finally enjoy the moment that they've long been hoping for. The crowd cheering at their procession appears just as stunned as the rebels by this quick victory. The battle for Goma barely lasted 24 hours, a crushing defeat for the Congolese Army, which was sent running by a small force of around 2,000 rebels who walked into the city center unscathed on Nov. 20. Goma, the capital of North Kivu in eastern Congo, is quite the wartime booty for these bush fighters—part of a group called the M23—who spent the past six months holed up in a village that lacked a decent bar. "My friend, can you believe how nice this is?" exclaims Kazarama, the rebel spokesperson, entering one of Goma's best restaurants the next day.

Back in May when the rebellion started, nothing hinted that the M23 would go so far. After defecting from the Congolese Army in April, the rebels were chased by the government forces and cornered in a small enclave at the border with Uganda and Rwanda. "We walked for days, with little water to drink and only cabbage to eat. When we took position on the hills in Runyoni, we were bombed relentlessly and had to live in trenches," Séraphin Mirindi, an M23 colonel, recalls proudly.

Last week, the M23 agreed to withdraw its troops from Goma, but as of press time their positions hadn't changed and several members of the rebel group appeared reluctant to leave the city a week after the conquest.

The M23 is a small force of seasoned fighters, issued from a long line of Rwandan-backed rebellions that have been partly responsible for the violence shaking eastern Congo since the mid-'90s. "I am a career rebel," jokes Mirindi, who, like most M23 rebels, was part of the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP), an armed group led by the charismatic Laurent Nkunda, which controlled a large swath of the North Kivu province between 2006 and 2008.

Following a peace agreement in 2009, Nkunda was betrayed by his second-in-command, Bosco Ntaganda, and put under house arrest in Kigali, Rwanda. The CNDP troops integrated into the Congolese Army, and officers were given high-ranking positions, including a position of general for Ntaganda, despite a pending arrest warrant by the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

Thanks to those high-ranking positions and the weakness of the Congolese government, Ntaganda and the former CNDP officers were able to maintain a parallel chain of command in eastern Congo for three years. The mafialike network they established gave them access to areas of land rich in mineral resources, and allowed them to run businesses worth millions of dollars a year. With this kind of money, Ntaganda was able to enjoy a comfortable life in Goma, playing tennis and eating in fancy restaurants, while still finding enough time to relax on the farm he owned on lush green hills near the city.

But by the beginning of 2012, this lifestyle was jeopardized by President Joseph Kabila's decision to redeploy the former CDNP troops in other provinces of Congo, in a bid to reassert his leadership following contested elections. The plan backfired when Ntaganda defected with hundreds of men in tow. He was soon met by Sultani Makenga, the current military leader of the M23. At the time, the rebels claimed the only aim of the movement was to demand from the government the application of the peace agreement signed on March 23, 2009. (The date is the source of the group's name.)

Unlike the CNDP, which infamously used mass rape as a weapon of war and which employed a strategy consisting more of brute force than diplomatic compromises, the M23 is waging a war of public relations and appearances. The rebel group has a Facebook page and a website featuring pictures of smiling, friendly-looking soldiers. Kazarama, eager for media attention, had his personal phone number hand-printed on the first press releases issued by the movement. Ntaganda, given his indictment for war crimes by the ICC, has been a liability for the rebel force keen to keep an impeccable public image, and the M23 denies that it has anything to do with him. "I do not know where he is, but he is certainly not with us," says Makenga, a half-smile spreading on his face.

Sitting on a campaign chair in the Congolese army military academy that the rebels took over a few months ago, Makenga clearly is not keen to talk too long to a journalist. His answers are curt and often preceded by a mocking laugh. The interview has been granted only because another member of the M23 revealed to Newsweek that Makenga held meetings to prepare the rebellion as early as January and let slip that "important Rwandan people" were backing the armed group. Tall and handsome, but lacking in charisma and eloquence, Makenga would rather stay away from the press. A military man through and through, he was nowhere to be seen for a couple of days following the capture of Goma, preferring to carry on with his men to Sake and Mushaki, two villages the rebels seized after the capital of North Kivu.

In the space of a few months, the rebels' advance has been huge. "Our mission is not to conquer territory, but to demand that our rights are respected," Kazarama said back in June. At that time, looking worn out and tired, the movement's military spokesperson was rather humble and hesitant as he spoke on a muddy path. Five months later in Goma, Kazarama is prancing around the town with aplomb, telling anyone who wants to listen that the M23 will go all the way to Kinshasa, some 1,600 kilometers west of Goma, to remove President Kabila from power.

"We believe Kabila was reelected during fraudulent elections," which were held in November of last year, said Jean-Marie Runiga, the president of the M23's political branch, at a recent press conference. Ironically, the M23 men, who were still in the Congolese Army at the time, actively participated in fraud during the elections by coercing people into voting for Kabila, undermining somewhat the credibility of their posture against him today. "The M23's purpose is to defend the economic interests of the armed group's members and allow them to carry on their economic predation. There is no ideology behind the movement," said Marc-André Lagrange, senior analyst at the International Crisis Group.

However the M23 is not simply a movement of arrivistes. Behind the rebels, much bigger powers are pulling strings and defending their own interests in the region. A series of United Nations reports published this year have revealed how Rwandan and Ugandan top officials have been leading and supporting the rebellion by providing men and supplies, at the risk of sparking a new regional war. In 1998, rebellions backed by Rwanda and Uganda triggered a conflict that subsequently involved eight countries and killed an estimated 5 million people. Both countries strongly deny having anything to do with the M23, and the rebels themselves accuse U.N. experts of fabricating the evidence in the report.

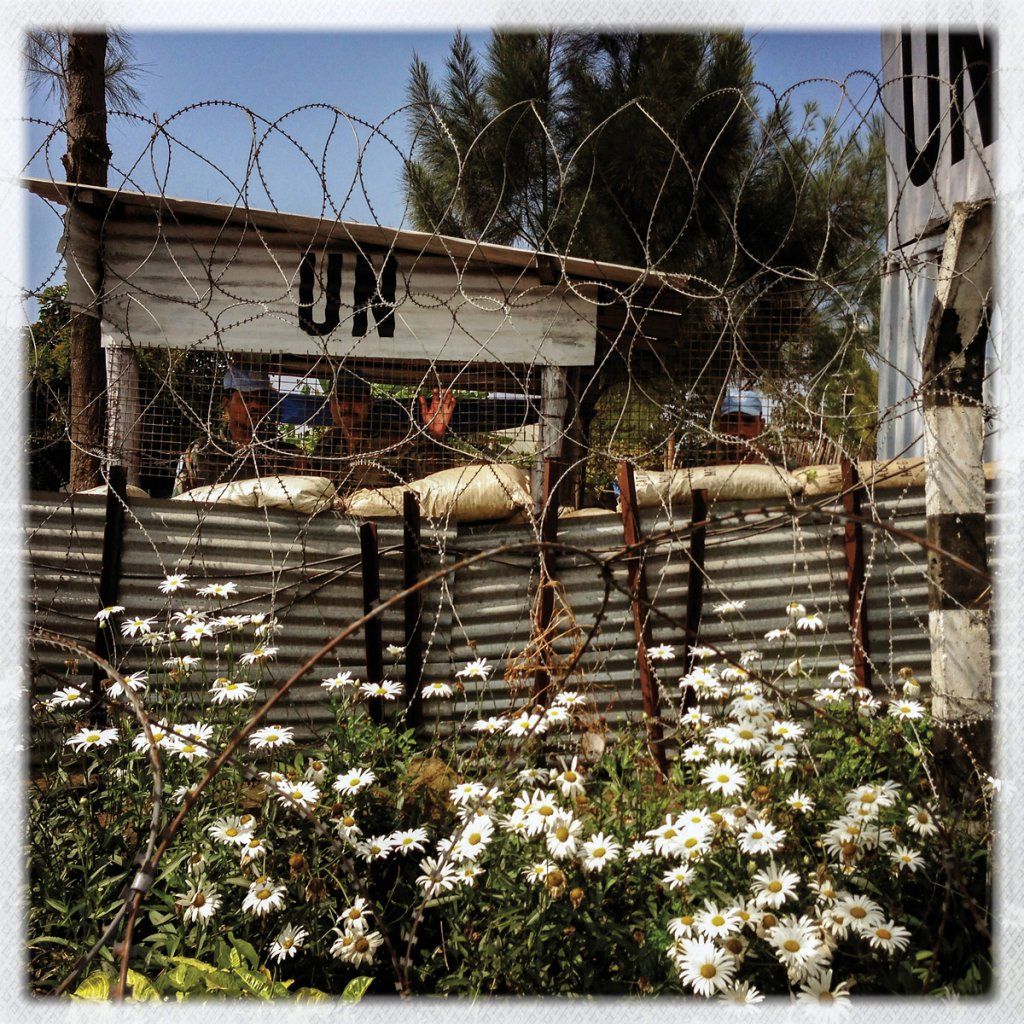

But at a U.N. base in Goma, a group of half a dozen young Rwandan men who escaped from the M23 in May stand as evidence of Congo's neighbors' hypocrisy. Recruited in Rwanda and told they were going to join the Rwandan national army, they found themselves in the hills of eastern Congo a few days later, roughly trained and given weapons to fight alongside the rebellion. "I didn't understand at first. Now I want to go home, my family doesn't know where I am," says one of the young men.

The stakes are high for Rwanda, even more so than Uganda, to maintain control over what is happening in the Congo, its chaotic neighbor. Following the Rwandan genocide in 1994, Hutu militiamen responsible for the death of thousands of Tutsis fled into Congo and regrouped, vowing to come back to Rwanda one day to finish the job. Although the fear entertained by Paul Kagame's regime over a potential génocidaire comeback has legitimate grounds, it has also been exploited by Rwanda as an excuse to interfere in eastern Congo and benefit from the country's natural resources. The Enough Project, a Washington-based advocacy group, revealed in several reports that minerals such as gold, coltan, and cassiterite were smuggled in vast quantities across the Congo-Rwanda border, thanks to Ntaganda's criminal network.

Allegations that the M23 is a proxy force for Rwandan dominance in eastern Congo has time and again been rejected by the group, which depicts itself as a revolutionary movement rather than a rebellion, subtly hinting at the Arab Spring.

"We will take Bukavu [the capital of South Kivu] and the population will rise and free itself," says Stanislas Baleke, a gentle academic who left his house and life in France to join the movement in August. "I learnt the idea of the revolution in France, making your ideas heard on the street. I want to apply this to my country now," he explains.

Baleke is the minister of tourism and environment in the so-called rebel administration. As the armed group conquered more and more territory, they created a parallel government to administer their fiefdom, with the intention of showing that they are a valid alternative to Kabila's rule. The organization is complete with a ministry of interior, a ministry of foreign affairs, and a ministry of agriculture, among others. What the ministers actually do, however, remains unclear. Ali Musagara, the minister of youth and education, is a plump man with a jovial smile who likes to display his three phones during meetings. Very much on top of things when it comes to recruiting young people for the M23 army, he remains elusive regarding how the movement will fund schools and sports programs.

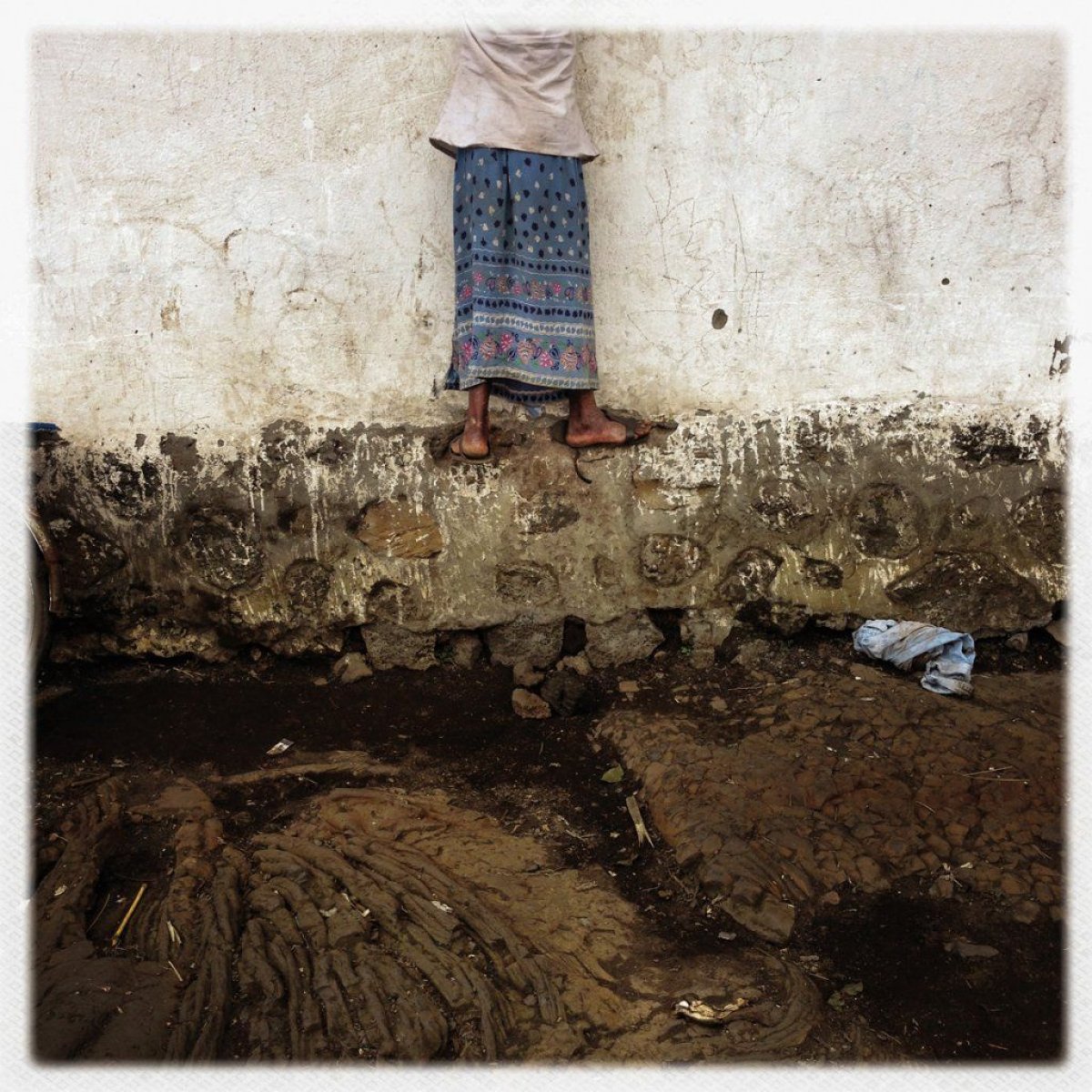

Whether their claims to be fighting for the betterment of the population's living conditions are blatant lies or the expression of a naive idealism that does not take into account the reality of eastern Congo, the M23 political cadre seems to be insensitive to the humanitarian crisis the armed group has triggered. In the space of a few months, more than 300,000 people have been displaced, adding themselves to the already 2 million displaced across the country. Many of them have been displaced several times. As the M23 advances, it is sending people fleeing from one camp to another, leaving everything behind them every time. And it's an endless struggle for humanitarian organizations, who must start afresh every time in a new location and raise new funds amid a generalized donor fatigue for eastern Congo.

"The challenge for us now is that we have invested in the site of Kanyaruchinya"—which was overrun by the rebels as they marched on Goma—"and we have to start from zero again in another camp. It takes time and it is expensive, and meanwhile displaced people need help," says Tariq Riebl, humanitarian coordinator for Oxfam.

As if putting thousands of people out on the roads was not enough, the rebels have also tried to take credit for the good actions of others. Deprived of water and electricity for days as Congolese Army soldiers shot down power lines on their way out of the city, Goma came back to life thanks to the efforts of Emmanuel de Mérode, the director of the Virunga National Park, who obtained a grant from park supporter Howard Buffett to buy generators as a measure to reinstate the city's electricity and water system. The M23 boasted that they were the ones who fixed the problem.

"I would like to believe that they are better than Kabila, or the rest of our corrupted political class," said Ernest Mugisho, a 45-year-old father of five. "But I know they are not the solution for my children's future. They do not have the will nor the capacity to help us. They will leave us nothing. They want privileges they were already given before, they want more, and they will leave us nothing."

Melanie Gouby is a freelance journalist based in Goma. She contributes to the AP, Le Figaro, and Radio Netherlands Worldwide, among others.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.