The idea that our universe is just one of many—part of a multiverse—has long fascinated scientists, fiction writers and philosophical thinkers alike.

It's a hotly debated issue among the research community, not least because many argue it is impossible to test. But most proponents of the hypothesis have tended to agree that the majority of alternative or parallel universes would be inhospitable to life as we know it.

However, new research conducted by scientists from Durham University, Western Sydney University and the University of Western Australia has demonstrated that other universes may in fact harbor the conditions to support life—if they exist.

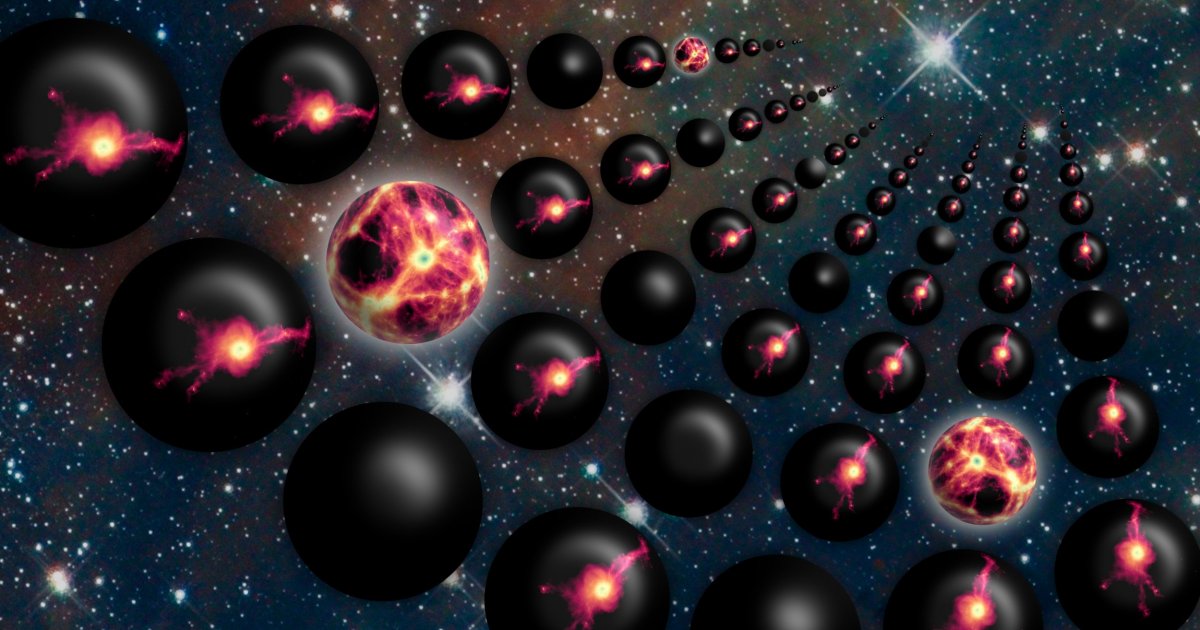

"The multiverse theory suggests that our universe is only one of many, baby universes being born like bubbles in a bigger multiverse, with a wide range of physical laws and fundamental constants," Jaime Salcido, a postgraduate student at Durham's Institute for Computational Cosmology, told Newsweek. "Only a tiny fraction of the baby universes are born such that they have the right amount of dark energy—the mysterious force that is accelerating the expansion of the universe—to be hospitable for life.

"The existence of life seems to depend on a small number of fine-tuned fundamental physical constants, such as the strength of gravity and the amount of dark energy," Salcido continued. "The formation of stars and galaxies is the result of a tug-of-war between these values: gravity causing matter to clump together, the dark energy causing the universe to fly apart."

Previous theories regarding the origin of our universe predicted the presence of much more dark energy than scientists think exists; the best estimates suggest that the theoretical energy makes up around 70 percent of all energy in the universe.

If our universe had more dark energy than this, there would be such rapid expansion that matter would be diluted to the extent that no planets, stars or galaxies would form—meaning humans, along with all other life, would never have evolved. That is why some scientists have proposed the multiverse theory: as an explanation for the "special" amount of dark energy in our universe.

"The multiverse theory tries to explain these fine-tuned constants as a lottery. We have a lucky ticket and live in the universe that forms beautiful galaxies that permit life as we know it," Salcido said.

To understand more, the researchers made use of one of the most realistic computer simulations of the observable universe: the EAGLE (Evolution and Assembly of GaLaxies and their Environments).

The researchers adjusted the physical constants of the simulation, finding that even when they added up to a hundred times more dark energy than what is indirectly observed in our universe, planet and star formations still continued.

"Our recent computer simulations of the universe, the EAGLE project, have been successful at explaining many observed properties of galaxies in our universe," said Salcido. "Our research shows that even if there was much more dark energy, or even very little, in the universe, then it would only have a minimal effect on star and planet formation, raising the prospect that life could exist throughout the multiverse."

The findings, which will be published across two papers in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, cast doubt on the ability of the multiverse theory to explain the observed amount of dark energy in our universe, according to the researchers.

While this doesn't rule out the possibility of a multiverse, they said, it does mean that an as yet undiscovered law of nature would be required to explain the dark energy conundrum.

"It seems that we need a new physical law to understand dark energy," said Salcido. "The puzzle remains."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.